Archive of Swine Flu Pandemic

Communication Updates

Archived Communication Updates Table of Contents

- June 29, 2010

- The “Fake Pandemic” Charge Goes Mainstream and WHO’s Credibility Nosedives

- January 17, 2010

- Pandemic Interruptus: It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over

- December 15, 2009

- What the CDC Is Saying about Swine Flu Severity

- December 15, 2009

- Update on the December 2 Update

- December 2, 2009

- It’s Official (sort of): The Swine Flu Pandemic Is Mild So Far

- November 18, 2009

- U.S. Pandemic Vaccine Supply and Distribution: Addressing the Outrage

- September 26, 2009

- Overselling Seasonal Flu Vaccination in a Pandemic Season

- August 21, 2009

- Talking about Pandemic H1N1 Vaccination

- July 21, 2009

- The Three-Legged Stool of Pandemic Messaging

En Français: Le tabouret à trois pattes de transmission de messages pour la pandémie

- July 7, 2009

- Why Pandemic Complacency Isn’t OkayEn Français: Pourquoi en cas de pandémie l’insouciance n’est-elle pas acceptable?

- June 17, 2009

- Would you like another wakeup call?En Français: Souhaiteriez-vous un autre appel de réveil?

- June 4, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Prospects: Nobody Knows

- May 23, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Prospects: Nobody Knows

- May 16, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Prospects: Nobody Knows

- May 6, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Prospects: Nobody Knows

- April 29, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Scare Gets Serious

- April 28, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Scare Gets Serious

- April 26, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Scare Gets Serious

- April 24, 2009

- Swine Flu Pandemic Scare Gets Serious

June 29, 2010

The “Fake Pandemic” Charge Goes Mainstream

and WHO’s Credibility Nosedives

by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard

The last Swine Flu Pandemic Communication Update on this site was January 17 – five months ago. It made four points:

The last Swine Flu Pandemic Communication Update on this site was January 17 – five months ago. It made four points:

- We don’t know what’s coming next.

- It’s a real pandemic.

- It’s a mild pandemic, at least so far.

- It’s probably not over – but we don’t know what’s coming next.

That’s about it, really – still … except for the blame game, which is what we are going to analyze below. The extremely long assessment that follows advances an argument we can summarize in a single sentence:

The absurd charge that the World Health Organization (WHO) hyped a fake pandemic in order to enrich Big Pharma has gained undeserved mainstream credibility mostly because WHO has badly mishandled its risk communication about three issues: (a) the mildness of the pandemic (so far); (b) the debatable meaning of the term “influenza pandemic”; and (c) the inevitable – but not culpable – structural conflicts of interest of WHO advisors.

That’s where we’re going.

Where is the pandemic going? In January, swine flu incidence in the northern hemisphere had peaked and was decreasing in many countries, but was still widespread. Now, as summer approaches, it’s quite low. It’s quite low in the southern hemisphere too, but with somewhat higher levels reported in some tropical countries. Seasonal H3N2, the most severe of the seasonal strains, is still circulating at low levels. At this point, unfortunately, it does not appear to have been replaced by the pandemic virus.

In other words, there is no clear evidence yet that pandemic H1N1 is or is not going to “act” like a seasonal flu strain from now on, which is what former pandemic flu strains have done after 1–3 years. That’s certainly one of the possibilities, but there are two others. It could cause additional pandemic waves more or less like the ones it has already caused. Or it could get a lot more virulent – which most experts don’t expect at this point but don’t rule out either. (Experts do remember that the mild 1968 pandemic returned to cause a more severe European wave in the winter of 1969–1970, a full year after the very mild first European wave. Almost anything is possible with influenza.)

The pandemic is like a hurricane that initially and briefly looked like it might be a Category 4 whopper, turned out to be just barely a Category 1 hurricane – but still a hurricane – and then dissipated. But unlike a dissipated hurricane, the pandemic isn’t completely gone.

In our daily lives, though, the pandemic feels like it’s over, and for some people it feels like it never happened. Other than ongoing vigilance (surveillance and assessment), precautions are in abeyance in most of the world. The most expensive precaution, a new vaccine, wasn’t ready until after the 2009 northern and southern hemisphere waves were over or receding. Still, the vaccine could have prevented a lot of morbidity and some mortality if it had been ready sooner. And if the pandemic comes roaring back, many people will wish they had availed themselves of the vaccine they so disdained as the last wave receded.

Today, the only individuals continuing to take pandemic precautions are obsessed, and the only individuals complaining that we should never have taken precautions in the first place are ignorant.

As we write this in late June 2010, there is now a huge gap between WHO’s pandemic risk communication and the public’s pandemic risk perception. That is, what most people think they just lived through – a mild pandemic that has virtually disappeared – is radically different from what WHO tells them they are living through: a “moderate” pandemic that is still ongoing.

The result: Widespread skepticism about WHO’s credibility, and thus widespread receptiveness to previously fringe allegations.

“Widespread” is a relative term here. Most people pay virtually no attention to the World Health Organization. They didn’t realize it had a lot of credibility, and they didn’t notice when its credibility collapsed. And WHO’s most devoted followers – many of them public health professionals – have tended to rally round the organization in its hour of need. (Some of them have supported WHO publicly while muttering to each other that it really should stand down from some of its earlier pronouncements.)

But there’s a super-important group in the middle: people who don’t follow WHO closely but who do pay enough attention to have learned first that it seemed to be overstating the seriousness of the swine flu pandemic and then that it was accused of doing so on purpose to help Big Pharma make big bucks. That group includes many of the world’s opinion leaders: corporate executives, government officials, medical reporters, foundation heads, etc. Losing ground in their eyes matters for WHO, and may continue to matter for decades to come.

The collapse of WHO’s credibility is important not just in general because the world needs a credible international health agency, but also, in particular, because WHO’s pandemic warnings about the future (though not its status reports about the present) are right on target. H1N1 could mutate into a much deadlier virus. That would be unusual after a year, but not unprecedented. The world could also face another pandemic in the near future, caused by another novel flu virus. There was apparently a flu pandemic in 1830–31 and another in 1833. The 1968 pandemic started less than ten years after the 1957 pandemic ended. And of course all flu-watchers know that the extremely deadly H5N1 bird flu virus is still Out There. If bird flu ever starts transmitting easily from humans to humans, it’s a whole new ball game.

It is very hard for WHO to convince people – governments, journalists, ordinary citizens – to take the near-term pandemic risk seriously as long as WHO keeps describing the past year’s pandemic experience in ways they simply cannot take seriously.

The one-year anniversary of the identification of the new swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus came in late April, 2010. The media ran a lot of anniversary stories. Some health agencies issued anniversary news releases, often featuring “lessons learned” about what had gone well and not so well. The Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota did a whole series of anniversary stories. In preparation for one on communication lessons learned, Lisa Schnirring of CIDRAP sent us a list of questions. We dutifully wrote answers and posted them on this site.

The one-year anniversary of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration of a full-fledged “Phase 6” pandemic was June 11, 2010. There were only a few anniversary stories.

This site’s Swine Flu Pandemic Communication Update about the Phase 6 declaration, posted on June 17, 2009, was entitled “Would you like another wakeup call?” It noted that: “For those who were already awake to pandemic realities and possibilities, [the WHO pandemic declaration] was basically a nonevent – a welcome if belated confirmation of what we knew.”

But in retrospect, the WHO pandemic declaration a year ago looks to many (though not to us) like a big mistake, or even an intentional deception. It was already pretty clear by mid-June 2009 that the pandemic was mild so far, more like the last two pandemics than like the nightmare possibility experts had warned about. But it was early days yet. It was perfectly possible that the pandemic could become much more virulent. (The first wave of 1918’s horrific pandemic was also mild.) Now, a year later, that possibility looks much slimmer. It can’t yet be ruled out; flu is famously unpredictable. But at this point it would be a big surprise. And so, with 20-20 hindsight, a lot of people think the initial pandemic declaration was unjustified.

Four things happened in early June 2010 that make this a compelling risk communication story, a fit but sad ending to the saga of Swine Flu Pandemic Risk Communication (Volume One).

WHO sticks to Phase 6.

On June 3, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan issued a statement summarizing the results of a June 1 teleconference meeting of the Emergency Committee that advises WHO on the H1N1 pandemic.

Dr. Chan said that “while pandemic activity is continuing, the period of most intense pandemic activity appears likely to have passed for many parts of the world.” That wasn’t sufficient, however, to persuade the committee to advise her to downgrade the pandemic to WHO’s “post-peak” phase, when “pandemic activity appears to be decreasing” but “it is uncertain if additional waves will occur.” All of the supporting data in the June 3 statement would seem to match the WHO definition of “post-peak,” but WHO did not stand down from Phase 6.

Nor did WHO seize the opportunity to stand down from its insistence that the H1N1 pandemic has been “moderate” so far, as opposed to “mild.”

The Council of Europe attacks WHO.

Also on June 3, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe published an utterly bizarre report  reiterating charges that WHO had foisted on the public a fake pandemic, and had done so partly in order to enrich the pharmaceutical industry. To facilitate this deception, the report claimed, WHO changed its definition of the term “pandemic” and systematically avoided transparency and accountability mechanisms that would have publicly exposed the conflicts of interest that underlay the fraud.

reiterating charges that WHO had foisted on the public a fake pandemic, and had done so partly in order to enrich the pharmaceutical industry. To facilitate this deception, the report claimed, WHO changed its definition of the term “pandemic” and systematically avoided transparency and accountability mechanisms that would have publicly exposed the conflicts of interest that underlay the fraud.

The charges in the report were not unexpected, since they had been ventilated months earlier in public statements, a formal motion, and a hearing – at which WHO Special Advisor on Pandemic Influenza Keiji Fukuda was questioned. Still, publication of the report demonstrated Council support for the charges, even after hearing Dr. Fukuda’s defense. The Council of Europe isn’t part of the European Union; its decisions aren’t binding. But with 47 member states, it does influence public debate and sometimes future government decision-making.

BMJ joins the attack.

On the same day, BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) published an article charging that WHO committee members often have conflicts of interest that are not revealed to the public. The article was written jointly by the journal’s features editor and a journalist from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit group launched on April 26, 2010, “to expose the exploitation of the weak by the strong” and “to reveal the failures of those in power to fulfill the trust placed in them.”

The article focused on three members of an earlier WHO committee that in 2004 had advised WHO to recommend large national pre-pandemic stockpiles of antiviral drugs. It pointed out some connections between those three committee members and the companies that manufacture and sell antivirals.

Publication of the BMJ article and the Council of Europe report was coordinated. On June 4 the principal author of the latter, Paul Flynn, posted on his blog: “One of the joys today was giving evidence with the editor of the splendid British Medical Journal. We have never met before but we cooed in harmony and just avoided saying it was the Pharmas that did it.”

WHO responds to its critics.

WHO responded to the charges in a June 8 open letter to BMJ, and again in a June 10 response to both organizations. It asserted that the pandemic was real, that the definition of a pandemic had not changed, and that WHO’s pandemic decision-making was completely uninfluenced by commercial interests. But it conceded that changes were needed in transparency policies regarding conflict of interest.

That’s the big swine flu risk communication story now, the biggest in months: In June 2010, the credibility of the World Health Organization crashed and burned. Charges that it had manufactured a fake pandemic in deference to the economic interests of Big Pharma gained mainstream attention.

These charges gained traction at this time, in our judgment, not because they are valid (they are not) but because WHO has badly mishandled certain aspects of its pandemic risk communications.

WHO has made three fundamental errors. In diminishing order of importance, they are:

- Failing to acknowledge that the pandemic has been mild overall, and that its incidence is now quite low. By “mild,” we mean similar to certain previous flu pandemics that WHO has long characterized as “mild” or “relatively mild.” By contrast, WHO has insisted on calling this pandemic “moderate” instead. And its tone has often left people feeling as if it were claiming “severe.”

- Failing to acknowledge that WHO changed some flu pandemic definitions and descriptions just as H1N1 was emerging. The technical meaning of the term “influenza pandemic” is debatable, as is the question of whether a mild flu pandemic should be called a pandemic at all. When WHO changed some of its definitions and descriptions of flu pandemic phases in ways that de-emphasized severity, it opened the door to suspicion that it had “changed the definition of a pandemic” in order to make sure H1N1 would qualify.

- Failing to acknowledge – until June 2010 – that WHO transparency about conflicts of interest had become inadequate. WHO’s earlier response to conflict-of-interest charges was to explain its policies and offer reassurance that the policies work. It wasn’t until after the two recent attacks that WHO began to concede that in the face of the public’s profound loss of trust, it may need to be both tougher and more transparent about its expert advisors’ conflicts of interest.

We must immediately concede that “failing to acknowledge” in these three bullet points is an overstatement. In their millions of words about the swine flu pandemic, WHO officials have periodically made statements that can be read as acknowledging all the points we’re accusing them of failing to acknowledge. We would be on safer ground claiming that WHO officials have failed to get these acknowledgments across. But that would imply that they were trying to do so. They weren’t. The main thrust of WHO pandemic communications has been, and continues to be, that H1N1 is a pandemic of moderate intensity that requires a continued “Phase 6” response; that H1N1 unambiguously meets the consensus definition of an influenza pandemic which has not been changed; and that WHO deliberations about how to manage H1N1 have been sufficiently transparent and self-evidently free of dangerous conflicts of interest.

That, we believe, is why WHO’s credibility is seriously threatened, and its ability to warn the world about future pandemic threats seriously compromised.

To understand what is behind the serious recent damage to WHO credibility, we are going examine these three failures in detail.

Such a detailed examination is worthwhile, we think, for two reasons:

- First, we hope to make a contribution to the world’s understanding, and to WHO’s understanding, of what happened – of how the World Health Organization managed to do severe damage to its own credibility – not by the way it handled the technical side of the twenty-first century’s first influenza pandemic (it did a creditable job), but by the way it handled its risk communication during that pandemic. WHO has appointed an external review committee

chaired by Dr. Harvey Fineberg to assess the “Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in Relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.” We hope this long column will help Dr. Fineberg’s committee see the pivotal role risk communication has played in WHO’s pandemic credibility crisis.

chaired by Dr. Harvey Fineberg to assess the “Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in Relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.” We hope this long column will help Dr. Fineberg’s committee see the pivotal role risk communication has played in WHO’s pandemic credibility crisis.

- Second, we believe we are writing not just about what happened, but also about what happens. The H1N1 pandemic is not the only time WHO’s top scientists’ inattention to risk communication has been its Achilles heel, and WHO is not the only organization that has been damaged by its technical leaders’ inattention to risk communication. Many of the more specific phenomena discussed in this article – for example, WHO’s reluctance to make changes that might be seen as caving in to pressure – are also generic. We hope readers who don’t share our longstanding fascination with the World Health Organization and with influenza pandemics will nevertheless find parts of this analysis illuminating.

For readers who don’t want to delve that deep, we hope the foregoing introduction will have been of interest. For the remainder of this lengthy analysis, use the following links:

Complete Column Table of Contents

January 17, 2010

Pandemic Interruptus: It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over

by Peter M. Sandman

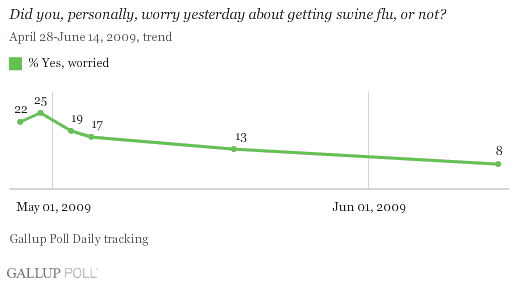

What should pandemic risk communicators be saying in January 2010, when swine flu looks to non-experts like it’s disappearing, when swine flu vaccine is a drug on the market, and when swine flu news has taken on a distinctly skeptical tone?

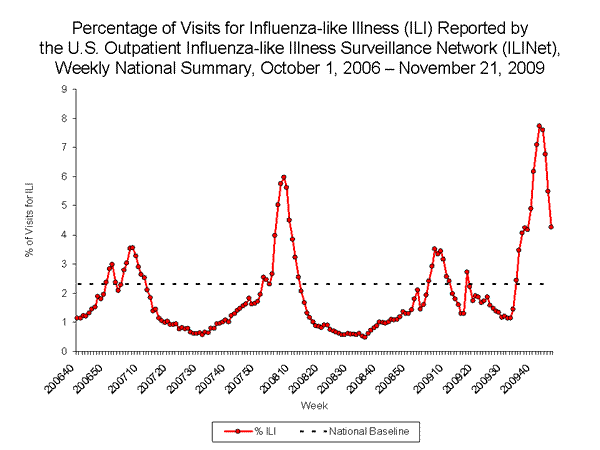

It has been a wild ride so far, from high drama to bored skepticism in a mere nine months. The novel H1N1 influenza virus was first identified in samples from two U.S. children in mid-April 2009, and then a week later in samples from Mexico. April is a month when there’s normally very little flu in the northern hemisphere. From April through December, the U.S. had more flu than in the average flu season. In most of the country, but not all, we saw a first wave in the spring, then a summer decline (but still much more flu than usual in summer), and then a bigger second wave in the fall. Then the fall wave plummeted.

By mid-January in most years, seasonal flu numbers are increasing in the U.S. But in this pandemic year, the pandemic flu numbers are decreasing, and there is virtually no seasonal flu around yet. The same thing is happening in most of Europe. Pandemic H1N1 is way down, and except for a few isolated cases seasonal flu has yet to appear.

Naturally the media have virtually decreed the pandemic over. And some commentators have said, in hindsight, that it wasn’t a pandemic at all.

In the ecosystem of public opinion, all niches are filled. At one extreme are those who confidently predicted a rerun of 1918 or worse, some of whom even now maintain that it happened and health officials somehow managed to cover it up. At the other extreme are those like Marc Siegel and Michael Fumento who were pandemic scoffers from the outset and are now crowing that they were right all along.

Many in the media have happily oscillated from one extreme to the other. Some of the newspapers and broadcast stations that headlined the direst predictions now headline preposterous charges that it was a “false pandemic” manufactured by a conspiracy of public health officials and pharmaceutical companies.

Okay, so what should pandemic risk communicators be saying?

1. We don’t know what’s coming next.

Although people with normal interests may think of flu as ordinary and boring, public health experts see influenza as endlessly surprising, among the most fascinating of diseases. And influenza is never more surprising than when a new flu virus emerges and launches a pandemic.

Although people with normal interests may think of flu as ordinary and boring, public health experts see influenza as endlessly surprising, among the most fascinating of diseases. And influenza is never more surprising than when a new flu virus emerges and launches a pandemic.

Experts see flu as unusually unpredictable – but considerable unpredictability is a hallmark of nearly all crisis situations. That’s why acknowledging uncertainty  is a core principle of crisis communication.

is a core principle of crisis communication.

The only sensible way to plan pandemic response – and the only sensible way to talk about pandemic planning – is probabilistically. We don’t know what’s next, but we can estimate probabilities and act accordingly.

Probabilistic thinking is the very essence of risk assessment and therefore of risk management. And probabilistic language is an essential part of risk communication.

Thinking and talking probabilistically about risk requires asking six core questions:

- What outcomes are possible?

- What is the estimated probability of each possible outcome? (No one can really know, but experts can make informed guesses.)

- What are the predicted effects of each possible outcome, and how bad is each set of effects? (This can be modeled.)

- What can be done, at what cost, to mitigate each set of effects? (This can be modeled too.)

- How confident are we about the answers to these questions? (Not very.) What are we likeliest to be wrong about? In which direction?

- Based on all of that, what does it make sense to do? (This will be a debatable judgment based partly on values and partly on the guesses and modeling above.)

It doesn’t follow that the wisest course of action is to prepare only for the likeliest set of outcomes. Dire outcomes justify preparedness (if preparedness is possible and cost-effective) even if they’re pretty unlikely. That’s why people buy fire insurance for their homes – not because a big fire is the likeliest outcome, but because it’s a very bad outcome that isn’t vanishingly unlikely.

Inevitably, then, a lot of preparedness will turn out unnecessary or excessive. When your home doesn’t burn down, you don’t cancel your insurance, nor are you angry that you wasted your premium. You’re glad your home didn’t burn down last year, and also glad you’re insured in case it burns down this year.

And fire insurance salespeople don’t claim that their prospective customers’ homes are going to burn down. They ground their sales pitch not in the probability of such a disaster, but in its magnitude. They’re selling a hedge to lessen the impact of a profoundly undesirable scenario – one that is pretty unlikely, but not so unlikely as to constitute a negligible risk. And they’re selling the peace of mind that comes with knowing you have hedged against such a possible disaster.

What’s missing from most people’s pandemic thinking is this probabilistic mindset.

Sports fans think probabilistically. Baseball fans, for example, know that there are times when the smartest thing for a batter to do is try to bunt the runner into scoring position. If the strategy doesn’t pan out, a commentator may remark that the batter probably wishes in hindsight that he’d swung for the fences … but nobody says he should have done so when the odds said bunting was the right bet. There are obvious analogues in virtually every sport: The right play remains the right play even when it didn’t work this time.

Similarly, we all understand that weather forecasters play the odds, and advise us to play the odds. When there’s a 70 percent chance of rain we take an umbrella to work and cancel our picnic plans – and we’re not especially outraged if the sun shines all day. When there’s even a 20 percent chance of a hurricane we buy extra food and check the flashlight batteries – and we feel neither foolish nor victimized if the hurricane weakens or changes course.

But in public health, non-experts often indulge in outcome-biased thinking instead of probabilistic thinking. Thus many people – and many journalists and politicians – seem to believe that officials should have prepared for exactly the pandemic we got (so far), no more, no less … as if they could have known in advance what sort of pandemic would come along.

If the 2009 pandemic had turned out as severe as it looked last April in Mexico, Congress would long since have launched investigations into why the CDC was insufficiently prepared, why we let our public health infrastructure decay, etc. If we end up with a severe third wave, those same questions will be asked. Even the mild pandemic we have had so far was sufficient for “tough questions” about the slow pace of vaccine production. But since the pandemic looks like it’s over (for now) and since it wasn’t very bad (for most people), many are asking instead why public health officials scared us unnecessarily.

I’m not going to burden readers with endless quotations from commentators and critics in the U.S., Europe, India, and elsewhere. They’re all grounded in the same false reasoning:

- Officials warned us that things might get really bad, and urged us to take precautions.

- Things didn’t get that bad (at least not yet). Those who took precautions feel foolish. Those who didn’t take precautions feel vindicated.

- Officials must have known that things wouldn’t get that bad. They misled us on purpose. Here’s why they did it….

Outcome-biased thinking isn’t confined to public health. Consider three other examples.

- After hurricane Katrina, most people came to believe in hindsight that the government should have done more to enable the New Orleans system of levees to withstand heavy floods in a strong hurricane. They didn’t think so beforehand, and they still don’t want to retrofit other cities against other catastrophes. There’s not much demand to prepare New York City for a tsunami or the New Madrid Fault region for an earthquake. Just New Orleans for a hurricane.

- After the financial system imploded in 2008-2009, just about everyone agreed that there should have been tougher regulation of credit default swaps, securitized mortgages, and whatever else needed regulating in order to keep the economy on track. Not that we wanted more government regulation at the time. Nor do we want more government regulation now … except for regulating whatever caused the economy to tank last year.

- After the Christmas Day bomb attempt on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, a near-consensus emerged that the government should have seen it coming and stopped Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab from getting onto the plane. Does that mean we want all people put on the no-fly list if they’re from countries with significant Muslim populations and their fathers think they’re too radical? Nope – just Abdulmutallab and everyone else who’s going to try to blow up a plane.

I’m not asserting that it’s a bad idea to spend more money preparing urban areas for natural disasters, or to regulate financial institutions and especially innovative financial instruments more strictly, or to be more rigorous in the screening of international air travelers. There are pros and cons to each of these measures. And there are counterexamples – horror stories of money spent preparing for natural disasters that never came, of industries that seem unable to compete and innovate effectively because of over-regulation, of innocent people who have struggled unsuccessfully to persuade officials to take them off the no-fly list.

My point is that you can’t prepare only for a hurricane in New Orleans, regulate only the industries that are about to implode, and keep only the actual terrorists from flying. And you can’t get people all worked up about only the pandemics that are going to turn out to have been severe.

You can be as risk-averse or as risk-tolerant as you want in how you play the odds. But you can’t avoid playing the odds.

In all these examples where post-hoc outcome-biased thinking prevailed over real-time probabilistic thinking, the situation was scary enough that many people felt powerless and vulnerable. Sometimes a degree of psychological regression happens when people feel powerless and vulnerable. We get childish and petulant. Like children, we want mommy and daddy to make it right.

So if something bad happens, we complain bitterly that mommy and daddy should have protected us better. And if something bad doesn’t happen, we complain nearly as bitterly that mommy and daddy shouldn’t have disrupted our playtime with unnecessary warnings and precautions.

These examples have something else in common. Discussions of sports and weather refer constantly to playing the odds – but discussions of emergency preparedness, government regulation, counterterrorism, and pandemic response do not.

Early on in the pandemic, public health officials should have been saying – again and again – something like this:

We don’t know how severe this pandemic is going to be. Yet we have to make decisions now – for example, decisions about how much vaccine to order, and decisions about whether to advise closing schools and canceling public events. So some of these decisions may end up wrong. We are trying to err on the alarming side. We’d rather prepare too much than too little. But if things get very bad, critics will say that we should have done more – and in hindsight they will be right. And if the pandemic turns out mild, critics will say that we should have done less – and in hindsight they will be right too.

Officials did say things like this from time to time. At the very start of the CDC’s second pandemic press briefing on April 24, Richard Besser (then acting director) put it superbly:

First I want to recognize that people are concerned about this situation. We hear from the public and from others about their concern, and we are worried, as well. Our concern has grown since yesterday in light of what we’ve learned since then.

I want to acknowledge the importance of uncertainty. At the early stages of an outbreak, there’s much uncertainty, and probably more than everyone would like. Our guidelines and advice our [are] likely to be interim and fluid, subject to change as we learn more….

We do not know whether this swine flu virus or some other influenza virus will lead to the next pandemic; however, scientists around the world continue to monitor the virus and take its threat seriously.

Media coverage of the Besser press briefing was substantial, but very few stories quoted this passage. Reporters went for the hard news: what the CDC thought was happening and what it was going to do about it. “Uncertainty claims” – explicit statements that the situation is uncertain, that officials are playing the odds, and that in hindsight their response may turn out too aggressive or not aggressive enough – are hard to get into the media. Officials almost always end up sounding more certain in news stories than they sounded during the news conference or the interview.

Later on, commentators who missed the qualifiers and uncertainty claims write, “Remember when they said we were all gonna die?”

Even if uncertainty claims make it into the media, they are hard to get into people’s heads – especially the heads of people who feel powerless and vulnerable, who want officials to be confident and definite.

And of course most officials are less committed than Dr. Besser was to communicating their uncertainty. Especially in crisis situations, it’s awfully tempting to project certainty instead (as if that were a stand-in for competence) – to give the anxious public what it seems to want.

But nothing is more important in pandemic risk communication than persuading the public (and the politicians) to think probabilistically. Public health officials need to insist on their uncertainty; they need to make uncertainty the message, not the preamble to the message.

Uncertainty about the future should have been stressed, over and over, early on in the pandemic – far more than it was. But maybe we’re still “early on” in the pandemic. As Yogi Berra (a probabilistic thinker) taught us, it ain’t over till it’s over. So probabilistic thinking should be stressed now as well – both about the decisions that have been made up till now, and about the decisions we face today.

As the 1957 Asian Flu pandemic was looming from a distance, the U.S. Surgeon General at the time, Leroy Burney, said:

I am sure that what any of us do, we will be criticized either for doing too much or for doing too little…. If an epidemic does not occur, we will be glad. If it does, then I hope we can say… that we have done everything and made every preparation possible to do the best job within the limits of available scientific knowledge and administrative procedure.

I doubt that it’s ever advisable to make “every preparation possible.” But Burney’s first sentence is right on target.

Uncertainty is Message #1.

2. It’s a real pandemic.

After many weeks of information-gathering, discussions with Member States, and expert debate, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the swine flu outbreak a pandemic on June 11, 2009. In January 2010, some commentators are trying to “undeclare” it.

After many weeks of information-gathering, discussions with Member States, and expert debate, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the swine flu outbreak a pandemic on June 11, 2009. In January 2010, some commentators are trying to “undeclare” it.

They’re wrong. It’s a real pandemic.

Like a lot of terms in public health, the word “pandemic” isn’t rigorously defined. But there is general agreement that an influenza pandemic has three defining characteristics.

A flu pandemic has to involve a novel influenza virus.

The flu virus that launches a pandemic must be different from other flu viruses that have circulated among humans in recent years. This means that most of the population will have no significant pre-existing immunity from past exposure to the flu, or to the flu vaccine.

Although “novel” is a matter of degree, virtually all flu experts agree that the H1N1 virus that emerged last April is novel enough. It is very different from the H1N1 virus that was responsible for the 1918 pandemic. That earlier H1N1 gradually became the seasonal influenza A virus in the years after 1918 (it may also have been a seasonal strain for about ten years before it became a dreadfully virulent pandemic strain); then H1N1 was supplanted by a different influenza A virus after the pandemic of 1957; then it re-emerged (most experts think because of a laboratory accident) and became seasonal again in 1977; it has been circulating seasonally ever since. The fact that both viruses are classified as A(H1N1) viruses doesn’t make them close relatives.

There was some discussion early on that older people might have some cross-immunity from exposure to the other H1N1 before 1957. This question is still being researched. But U.S. data show that people born before 1957 have a swine flu population mortality rate at least as high as people born after 1957.

A flu pandemic has to be widespread.

The “pan-” in “pandemic” is Greek for “all,” while “-demic” comes from “demos,” Greek for “people.” A disease outbreak doesn’t literally need to threaten “all people” to qualify as a pandemic, but there does need to be a large number of cases in a large number of age groups in a large number of places.

How many cases in how many age groups in how many places is, once again, subjective and debatable. But nobody seriously argues that 2009 H1N1 hasn’t been widespread enough.

What enables a pandemic to become widespread is its ability to transmit efficiently from one person to another. Once health officials determine that an influenza virus has mastered efficient human-to-human transmission, they know the virus will soon be widespread.

-

A flu pandemic has to cause serious illness.

A novel flu virus that infected hundreds of millions of people all over the world still probably wouldn’t end up labeled a pandemic virus if it caused mostly mild illness and no excess mortality in any age group. Flu experts would certainly watch it closely in case that pattern started to change. Officials might even declare a pandemic early on, before the severity level was known. But if it’s not a serious health threat at least to some groups of people, then it’s not a flu pandemic.

This is the criterion that’s most controversial with regard to the 2009 pandemic. Throughout this pandemic, and especially lately in Europe, there has been a lot of scoffing that officials were scare-mongering, expending huge amounts of resources on a “false” pandemic.

On the one hand, millions of people in the U.S. alone have been sick enough to feel truly rotten, and around 11,000 of them have died – far more of them under age 65 than in an average flu season. That’s excess mortality in certain age groups. And more people with swine flu have ended up in hospital intensive care units than during an average flu season. On the other hand, so far the 2009 pandemic has killed fewer people than the three flu pandemics of the twentieth century, which started in 1918, 1957, and 1968. So far, in fact, it has killed fewer people than many ordinary flu seasons, and its overall case fatality rate (the percentage of sick people who die) is much lower than the average seasonal flu case fatality rate.

But as a group of prominent influenza experts put it:

[P]andemics, like interpandemic influenza seasons, vary in severity, by the age groups most affected, the size of the populations affected and in their length. Therefore, it cannot be assumed a priori that pandemics will cause more mortality than interpandemic seasons.

For example, some flu seasons since the 1968 pandemic have been deadlier than that pandemic, partly because of the aging of the population since then, but also because of the increased virulence of the seasonal strain A(H3N2), which was originally the novel virus that caused the 1968 pandemic.

There’s a very practical argument against considering the 2009 pandemic too mild to count: Officials need to announce pandemics early so societies will know to ramp up their preparedness. It makes sense to wait until it’s clear that a novel flu virus is capable of causing serious illness. But waiting until the ultimate case fatality rate is known would mean declaring pandemics only after they’re over … which would defeat the purpose of declaring pandemics in the first place.

Keep in mind that 2009 was the world’s first experience with a pandemic declaration so close to the start of an actual pandemic. It is a sign of stunning progress since 1968.

Experts continue to debate the close cases. The Russian Flu of 1977 is a good example. It was caused by the re-emergence (probably from a lab) of a 1950 strain of human H1N1, and it quickly spread globally. But it mostly affected people younger than age 23 – people who hadn’t been around when that strain was circulating previously. And it did not cause excess mortality in any age group. A few experts consider the Russian Flu to have been a pandemic, but most do not.

In 1995, influenza expert Edwin D. Kilbourne said that “defining a pandemic is a little like defining pornography – we all ‘know it when we see it,’ but the boundaries are a little blurred.” Dr. Kilbourne’s wonderfully readable article discusses several examples of such blurriness, especially regarding the concept of a “novel” virus.

If worldwide disease surveillance had been good enough in 1977 to identify the Russian Flu outbreak at its inception, it might have been declared a pandemic – and then “undeclared” when more was known. But it would take a very fringe expert indeed to recommend “undeclaring” the H1N1 pandemic of 2009.

3. It’s a mild pandemic, at least so far.

Sometimes it seems like the world (the world of people interested in flu, at least) is divided into two camps: the people who think swine flu is too mild to call it a pandemic versus the people who think it’s a pandemic and how dare anyone call it mild!

Sometimes it seems like the world (the world of people interested in flu, at least) is divided into two camps: the people who think swine flu is too mild to call it a pandemic versus the people who think it’s a pandemic and how dare anyone call it mild!

I’m in the third camp, which feels like the smallest camp: the people who keep insisting that it’s a mild pandemic so far.

It’s certainly not – so far – the pandemic that health officials were expecting and dreading. That expectation was shaped by two anchoring frames.

The first standard of comparison is the pandemic of 1918, the most severe pandemic of modern times. The 1918 pandemic is estimated to have killed about 675,000 Americans – virtually all within a single year, though the pandemic actually lasted 27 months. Its case fatality rate in the U.S. was roughly 2% – compared to roughly 0.02% for the 2009 pandemic so far, about a hundred times lower.

The second standard of comparison is the incredibly deadly novel H5N1 (“bird flu”) virus that emerged in 1997. Bird flu has not gone pandemic (so far); it has infected fewer than a thousand people worldwide. But it killed nearly 60 percent of them – a case fatality rate 30 times worse than the 1918 pandemic, and 3,000 times worse than the 2009 pandemic so far. The nightmare that influenza experts have been living with since 1997, and are still living with today, is that bird flu will mutate in a way that makes it as transmissible as ordinary flu (or as swine flu), only thousands of times deadlier.

Flu experts prepared for the 2009 pandemic in the shadows of 1918 and bird flu. They shied away from the most horrific possibilities, but they never even considered the mildest possibilities.

U.S. experts, for example, developed a Pandemic Severity Index  (PSI) that had five categories. The PSI assumed that a pandemic would infect about 30 percent of the U.S. population. A Category 1 pandemic would have a case fatality rate of less than 0.1%, adding no more than 90,000 U.S. fatalities – still more than twice as bad as the average flu season. A Category 5 pandemic would have a case fatality rate of greater than 2 percent, meaning more than 1,800,000 U.S. fatalities – basically a rerun of 1918 or worse, with a much larger population. A bird flu pandemic would be off the scale in one direction. The swine flu pandemic we got is off the scale in the other direction … which may be why officials haven’t mentioned their PSI in quite some time.

(PSI) that had five categories. The PSI assumed that a pandemic would infect about 30 percent of the U.S. population. A Category 1 pandemic would have a case fatality rate of less than 0.1%, adding no more than 90,000 U.S. fatalities – still more than twice as bad as the average flu season. A Category 5 pandemic would have a case fatality rate of greater than 2 percent, meaning more than 1,800,000 U.S. fatalities – basically a rerun of 1918 or worse, with a much larger population. A bird flu pandemic would be off the scale in one direction. The swine flu pandemic we got is off the scale in the other direction … which may be why officials haven’t mentioned their PSI in quite some time.

I have been describing the swine flu pandemic as “mild” since before it was declared a pandemic – almost always adding the crucial qualifier: “so far.” I based my use of the word “mild” on evolving published data about this pandemic, compared to prior pandemics and average flu seasons, not on my own non-existent influenza expertise.

On May 6, I wrote: “Swine flu looks to be an extremely mild pandemic if it goes pandemic at all, despite WHO warnings that it may ‘come back with a vengeance’ in the fall.” On June 4, I wrote that it was “still mild.” On June 17, I wrote: “The big public health risk isn’t the relatively mild flu that’s circulating now…. Swine flu could come roaring back in a much more virulent second wave.” On July 21, I proposed three core pandemic messages. One was: “Pandemic H1N1 looks very mild so far.” Another was: “We must prepare for the possibility that pandemic H1N1 could become more severe.”

I kept arguing that a communicator who failed to acknowledge the current mildness of the pandemic could not credibly warn about its possible future severity.

Finally, on December 2, I entitled my Swine Flu Pandemic Communication Update: “It’s Official (sort of): The Swine Flu Pandemic Is Mild So Far.” The CDC’s own data showed the mildness of the pandemic, I said, and the CDC was unwisely refusing to say so.

This time I was criticized for insisting so aggressively on the pandemic’s mildness. (See my December 15 acknowledgment of this criticism.) I understand some of the reasons why the term “mild” strikes many as offensive:

- It is insensitive to the impact of the pandemic on those who lost a loved one to H1N1, or were severely ill, or even just worked 90-hour week after 90-hour week in a local health department.

- It ignores the reality that the pandemic has already killed several times as many children as the average flu season. (The average flu season kills mostly the elderly.) That’s a fact that has understandably and justifiably worried many parents, and left them feeling that the pandemic was anything but mild.

- It also ignores the reality that many more people under 65 were hospitalized and in intensive care units during the 2009 pandemic than during the average flu season. Often concentrated over a short period of time in specific “hot spots” around the country, these hospitalizations constituted an unusual burden on the U.S. medical system.

- It focuses on one aspect of pandemic severity, the number of deaths. But pervasiveness matters too. My college professor daughter, for example, says more of her students were out sick with the flu last fall than any semester in her memory. As far as she knows, none of them died. But she certainly experienced the fall as a severe flu season.

Despite all of that, the fact remains that in terms of overall mortality the 2009 pandemic has been very mild so far – so mild that some are denying that it’s a pandemic at all. The time has come for officials to acknowledge and insist on the middle ground. Yes, it’s a pandemic – so far a mild one overall, albeit tragic for tens of thousands of people around the world.

In fact, official acknowledgment of the pandemic’s mildness is long overdue. Both the CDC and the World Health Organization have steadfastly avoided the word “mild” in their pandemic communications. Both have passed up many chances to breathe an audible sigh of relief: when the alarming initial news from Mexico was not borne out, when the pandemic case fatality rate came in lower than the rate of prior pandemics and lower than the rate of the average flu season, etc. Both have seldom said publicly what I think they must be saying privately: “So far, so good. We’re not out of the woods yet, and the pandemic could still take a turn for the worse, but to date it has been much less devastating than we dared hope.”

In part because of their failure to acknowledge the pandemic’s mildness, officials are now reaping the whirlwind. Millions of ordinary citizens have seen for themselves that (with tragic exceptions) this pandemic is not such a big deal. If the CDC and WHO think otherwise, if what we have experienced over the past nine months is really the sort of pandemic health officials consider serious, then it makes sense to shrug off their pandemic warnings altogether.

Officials’ failure to acknowledge that the pandemic has been mild so far thus justifies public skepticism about officials’ warnings that this pandemic or some future pandemic could be far more severe. It even gives a semblance of credence to the absurd allegation that officials have been promoting a fake pandemic for ulterior purposes.

It’s a real pandemic, but so far a mild one. Officials need to say so.

4. It’s probably not over – but we don’t know what’s coming next.

I’m not a virologist, and I’m not entitled to an opinion about where the 2009 pandemic is headed in 2010. In fact, many virologists think they’re not entitled to an opinion either. They say it’s anybody’s guess.

I’m not a virologist, and I’m not entitled to an opinion about where the 2009 pandemic is headed in 2010. In fact, many virologists think they’re not entitled to an opinion either. They say it’s anybody’s guess.

The least likely possibility, I’m told, is that swine flu will simply disappear. Influenza is such an unpredictable disease that the experts aren’t ruling anything out, not even that. But the H1N1 virus transmits easily from person to person. And it has lots of people left to infect – people who have neither had the disease nor been vaccinated against it. So most experts expect to see more swine flu.

One question is when swine flu will surge again in the U.S. (It hasn’t disappeared. It is still circulating in low levels here, and at higher levels in some countries around the world.) There are three main possibilities:

- There could be a third pandemic wave soon – this winter, in fact. Some experts think that’s very likely, and none would find it surprising. But most countries in the southern hemisphere had a quick, steep, late-fall/early-winter pandemic first wave very much like our second wave … and have seen little or no swine flu since then. So maybe we’re done for this season.

- There could be a delayed pandemic third wave – in the coming spring, summer, or fall; or maybe not till the weather turns cold again next winter. Other pandemics have seen troughs of many months before a new wave, so it wouldn’t be a surprise if that happened again.

- Novel H1N1 could return not as a third pandemic wave but as a no-longer-novel seasonal influenza strain. Once pandemic flu viruses have run their pandemic course, they usually have a second life as seasonal strains. The last three pandemic strains supplanted the seasonal influenza A strain that had been circulating before the pandemic strain emerged. The distinction between a pandemic wave and a flu season with a new strain is a bit arbitrary. But sooner or later the pandemic swine flu virus is expected to turn into a seasonal influenza A strain – maybe even the only seasonal influenza A strain.

A more important question than when swine flu will resurge is how the novel H1N1 virus might change along the way. The scariest possibility is that it could become more virulent, mutating in a way that makes it much less mild. One nightmare scenario: Swine flu and bird flu mix-and-match genetic material, producing a new virus as infectious as swine flu and as deadly as bird flu.

All changes are possible. The swine flu virus could become more or less virulent. It could become more or less infectious. It could attack different age groups or people with different medical conditions. It could become resistant to antiviral drugs. It could (and almost certainly will, over time) drift genetically so the existing vaccine no longer works very well.

Or, of course, it could stay pretty much the way it is – with more and more people becoming immune to it as a result of previous exposure or vaccination. Influenza strains mutate incessantly, so “staying the same” is considered a pretty unlikely scenario. But as the experts all say, the only thing you can be sure of with influenza is that it will surprise you. Staying the same is one possible surprise.

And here’s yet another question: What’s going to happen to the seasonal flu strains? Precedent says one or both of the currently circulating influenza A strains will probably disappear, supplanted by the new flu in town. But that’s not guaranteed either.

If the U.S. is going to have its usual flu season this winter, it’s already a little late … but not yet ridiculously late. So:

- Maybe we’ll see no more pandemic flu this winter, but the seasonal flu will come back as usual.

- Maybe we’ll have to endure both simultaneously – a pandemic third wave plus the usual flu season.

- Maybe the previous seasonal influenza A strains will disappear for good, and swine flu will be our new seasonal influenza A until the next pandemic.

If swine flu does supplant the earlier seasonal A strains (whether it happens this winter or a year or two from now), that could be very good news, especially for seniors. In recent years seasonal influenza has been made up of two influenza A strains: H3N2 (still circulating since it caused the 1968 pandemic) and the 1977 version of H1N1. (There are also two kinds of influenza B in circulation. Influenza B doesn’t seem to compete with influenza A strains, and isn’t known to cause pandemics.) H3N2 is currently the deadlier of the two A strains, especially to the elderly. If H3N2 gets wiped out, and if pandemic H1N1 becomes seasonal and stays as mild as it is so far, we’re unlikely to reach our annual average of 36,000 U.S. flu deaths in the coming years.

In other words, by out-competing and replacing the deadlier seasonal strains (especially H3N2), the 2009 pandemic could end up saving lives!

Like everything else about influenza, this isn’t guaranteed either. Maybe swine flu will end up coexisting with one or both of the two seasonal influenza A strains that have been circulating since 1968 and 1977. Maybe it will supplant those earlier strains but become deadlier itself (just as H3N2 is deadlier today than it was during the pandemic of 1968).

Or maybe swine flu will disappear after all, leaving us back where we started.

Key Messages

So what are the key messages of the moment about the swine flu pandemic? I think there are four.

Like you, we don’t know what’s going to happen next either.

Flu pandemics are unpredictable. From the beginning, we have had to prepare for a wide range of possibilities – and we still do. We will continue to err on the alarming side, convinced that it’s better to over-prepare than to under-prepare, until we are sure the pandemic is over.

We probably haven’t seen the last of swine flu.

It may come back soon, or not for many months. It may come back as a pandemic third wave, or as a new seasonal strain. Either way, getting vaccinated now against swine flu is a sensible precaution.

So far the pandemic has been mild.

It sure didn’t feel that way if you were among its victims, or their families and friends. But the truth is, we were lucky (most of us). This isn’t the pandemic that health officials were worried about, at least not yet. It’s a real pandemic, and it has killed way more children than the average seasonal flu. But overall, it is less deadly so far than the average seasonal flu.

-

We may still face the pandemic officials were worried about.

Swine flu could mutate to become more severe. A new, worse pandemic could emerge – maybe bird flu; maybe something completely new. What has happened already is a tragedy for many people. But it is a practice run for all of us – not a false alarm – and we should see it that way.

December 15, 2009

What the CDC Is Saying about Swine Flu Severity

- How deadly is the pandemic so far?

- What age groups is it hitting hardest?

- What age groups does the government say it is hitting hardest?

by Peter M. Sandman

This update draws some inescapable tentative conclusions from the most recent (December 10) tentative estimates of U.S. pandemic flu cases, hospitalizations, and deaths provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This update draws some inescapable tentative conclusions from the most recent (December 10) tentative estimates of U.S. pandemic flu cases, hospitalizations, and deaths provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

On January 15, 2010, the CDC updated its estimates of U.S. swine flu cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to cover the period through December 12, 2009 – pretty much finishing out the second wave of the pandemic.

The additional month of data didn’t increase the numbers much, and didn’t change their implications at all. Everything in my December 15 update (which discussed the CDC’s December 10 report on data through November 14) applies equally to the CDC’s January 15 report.

But of course the exact numbers in this update are now out of date. Readers should feel free to do their own arithmetic to calculate updated case attack rates, case fatality rates, population mortality rates, etc., for each of the three age groups. It’s not that hard; just use this December 15 update as a template.

Note that the CDC webpage to which this update periodically links – http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/estimates_2009_h1n1.htm – now provides the CDC data through December 10. This is apparently going to remain the “evergreen” URL for the latest CDC estimate of swine flu cases, hospitalizations, and deaths (assuming there’s enough additional swine flu to justify any further reports). But the CDC has kept its earlier reports posted as well, with links from the evergreen page. The estimates on which this December 15 update was based are now at http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/estimates/April_November_14.htm.

(Added: January 16, 2010)

The update also contrasts the CDC’s estimates with CDC communication about them, and with the Department of Health and Human Services’ new H1N1 vaccination campaign, “Together we can all fight the flu,” launched on December 7.

I don’t have any opinion on whether the estimates the CDC reported on December 10 are reliable, valid, and useful. But I am certain that the arithmetic I have performed on those estimates to show what they mean is solid. And I am certain that what the CDC’s estimates mean diverges significantly from what the U.S. government is telling people about the pandemic.

Bottom line one is what the CDC’s December 10 estimates mean:

- Children (0–17) and adults (18–64) are much more affected, in terms of both deaths and hospitalizations, than they are in an average flu season. Seniors (65+) are much less affected than in an average flu season.

- Nonetheless, the pandemic so far is much less severe than an average flu season in terms of total deaths and hospitalizations per million cases. That is, a much higher percentage of people with swine flu than of people with the seasonal flu recover, and do so without requiring hospital care. This is true mostly because the pandemic is enormously less dangerous than the seasonal flu for people over 65, who account for 90% of all seasonal flu deaths in an average year.

- The pandemic case attack rate is much higher for children than for adults and seniors. So far, kids are likeliest to catch swine flu, by far.

- The pandemic case fatality rate is much higher for adults and seniors than for children. So far, kids are least likely to die if they catch swine flu, again by far.

- The pandemic population mortality rate is also higher for adults and seniors than for children. This is the most useful parameter for comparing the relative risk of different age cohorts. So far, adults and seniors are significantly likelier than kids to first catch swine flu and then die of a flu-related illness.

Bottom line two is what the public is being told:

- The official HHS pandemic vaccination campaign frequently says

children under 18 are most at risk.

- The vaccination campaign appropriately targets high-risk subgroups among young adults, but never mentions that, in general, adults 18 and older are at higher risk than children under 18.

- No vaccination campaign messages have prioritized seniors, even high-risk seniors, despite the fact that seniors’ population mortality rate is only slightly lower than that of adults 18–64, and much higher than that of kids under 18.

- The CDC’s news briefing on its December 10 estimates focused on the risk to children and young adults, implying that the risk was much lower to older adults and seniors. (The CDC may have information suggesting that younger adults in the 18–64 age group are at higher risk than older adults in that age group, but the December 10 CDC estimates do not include this information.)

- To the extent that the public continues to believe, mistakenly, that swine flu is deadliest to children and least deadly to the elderly, it seems likely that many older Americans may underestimate their own risk and therefore decide not to get vaccinated, even when vaccine finally becomes available to them.

This is my second time analyzing the CDC’s pandemic risk estimates compared to the CDC’s pandemic risk communication. On December 2, I posted an update that examined the implications of previous CDC estimates from the first six months of the pandemic. That update also criticized the CDC for failing to acknowledge the implications of its estimates, particularly in its November 12 press briefing.

The CDC’s first estimates included data through October 17, about a week or so before the peak of the second U.S. wave. The CDC’s second estimates, released December 10, include data through November 14, a couple of weeks after that peak. But there is still a lot more influenza (more cases, hospitalizations, and deaths) to come – and to be estimated – during the subsequent downslope weeks of the second wave.

Though the numbers all increased substantially from the first to the second set of CDC estimates, the proportions did not change much. In fact, little has changed in the implications of the CDC’s estimates, in what the public is being told, or in the gap between the two.

I made three main risk communication points in the earlier update:

- The CDC has conveyed a misimpression of how deadly the pandemic is and which age cohorts are most at risk of dying from it.

- If and when people become aware that they have been given a misimpression, the CDC risks sacrificing credibility – credibility it will need if this pandemic turns more severe; if another, more severe, pandemic arises; if controversies arise about vaccine safety; etc.

- The goal of motivating people (especially young people) to get vaccinated may make it tempting not to correct these misimpressions. But the price of reduced transparency and reduced credibility is too high. Sustainable public health leadership requires a very high level of candor, even if that candor may diminish achievement of a specific public health objective.

These points remain on target.

Analysis of the Three Age Groups

Children

0–17 | The CDC estimates 16 million cases, 71,000 hospitalizations, and 1,090 deaths.

U.S. Census data show that 24.3% of the U.S. population of 308 million is under 18; that comes out to 75 million children.

16 million cases out of 75 million children = 21.3% case attack rate

(21 sick children out of every hundred children)

1,090 deaths out of 16 million cases = 0.007% case fatality rate

(70 dead children out of every million sick children)

21.3% (CAR) × 0.007% (CFR) = 0.00149% population mortality rate

(14.9 dead children out of every million children in the population)

71,000 hospitalizations out of 16 million cases = 0.44% case hospitalization rate

(4.4 hospitalizations out of every thousand sick children)

1,090 deaths out of 71,000 hospitalizations = 1.5% inpatient mortality rate

(15 dead children out of every thousand children hospitalized)

|

Adults

18–64 | The CDC estimates 27 million cases, 121,000 hospitalizations, and 7,450 deaths.

U.S. Census data show that 62.9% of the U.S. population of 308 million is 18–64; that comes out to 194 million adults.

27 million cases out of 194 million adults = 13.9% case attack rate

(14 sick adults out of every hundred adults)

7,450 deaths out of 27 million cases = 0.028% case fatality rate

(280 dead adults out of every million sick adults)

13.9% (CAR) × 0.028% (CFR) = 0.00389% population mortality rate

(38.9 dead adults out of every million adults in the population)

121,000 hospitalizations out of 27 million cases = 0.45% case hospitalization rate

(4.5 hospitalizations out of every thousand sick adults)

7,450 deaths out of 121,000 hospitalizations = 6.2% inpatient mortality rate

(62 dead adults out of every thousand adults hospitalized)

|

Seniors

65+ |

The CDC estimates 4 million cases, 21,000 hospitalizations, and 1,280 deaths.

U.S. Census data show that 12.8% of the U.S. population of 308 million is 65 and over; that comes out to 39 million seniors.

4 million cases out of 39 million seniors = 10.3% case attack rate

(10 sick seniors out of every hundred seniors)

1,280 deaths out of 4 million cases = 0.032% case fatality rate

(320 dead seniors out of every million sick seniors)

10.3% (CAR) × 0.032% (CFR) = 0.00330% population mortality rate

(33.0 dead seniors out of every million seniors in the population)

21,000 hospitalizations out of 4 million cases = 0.52% case hospitalization rate

(5.2 hospitalizations out of every thousand sick seniors)

1,280 deaths out of 21,000 hospitalizations = 6.1% inpatient mortality rate

(61 dead seniors out of every thousand seniors hospitalized)

|

Comparisons by parameter

- Case attack rates:

- Children 21.3%

Adults 13.9%

Seniors 10.3%

The pandemic is likeliest to sicken children, and least likely to sicken seniors.

- Case fatality rates:

- Children 0.007%

Adults 0.028%

Seniors 0.032%

The pandemic is likeliest to kill sick seniors, and least likely to kill sick children.

- Population mortality rates:

- Children 0.00149%

Adults 0.00389%

Seniors 0.00330%

The pandemic is likeliest to first sicken and then kill adults; it’s nearly as dangerous to seniors, but much less dangerous to children.

- Case hospitalization rates:

- Children 0.44%

Adults 0.45%

Seniors 0.52%

The differences are small, but sick seniors are likelier to be hospitalized than sick adults or children.

- Inpatient mortality rates:

- Children 1.5%

Adults 6.2%

Seniors 6.1%

Hospitalized adults and seniors are much likelier to die than hospitalized children. (Note that some people die of influenza without having been hospitalized first; these deaths are part of the CDC’s estimated total number of deaths. Thus the number of deaths divided by the number of hospitalizations, reported here, is a rough and somewhat inflated measure of inpatient mortality rates.)

Some conclusions based on the December 10 CDC estimates

For the H1N1 pandemic:

- The age-specific case attack rates tell us that so far children 0–17 are most likely to catch swine flu.

- The age-specific case fatality rates tell us that so far seniors 65+ are most likely to die if they do catch swine flu.

- The population mortality rates tell us that so far adults 18–64 are most likely to do both: to catch swine flu and then die as a result.

The data do not permit assessment of younger versus older children (0–4 versus 5–17) or of younger versus older adults (18–49 versus 50–64) or of younger versus older seniors (65–74 versus 75+), though these finer distinctions may make a difference.

The pandemic is attacking a higher percentage of children than of adults and seniors. But among the three groups, the children are least likely to die.

It is nonetheless true that the pandemic is more deadly than the seasonal flu to children 0–17 and adults 18–64:

- Approximately 90% of the 36,000 seasonal flu deaths in an average year are 65 and over, leaving only 3,600 deaths among children and adults under 65.

- By comparison, 11% of pandemic deaths so far are children, 76% of the deaths are adults, and 13% are seniors. The U.S. population is made up of 24% children, 62% adults, and 13% seniors.

In other words:

- The seasonal flu discriminates overwhelmingly against seniors (65+) – seniors are 13% of the U.S. population and 90% of U.S. seasonal flu deaths.

- By contrast, the pandemic so far is discriminating against adults (18–64), though less overwhelmingly; adults are 62% of the population and 76% of the swine flu deaths.

- For both the seasonal flu and the pandemic so far, children (0–17) make up a much smaller percentage of the death toll than of the population.

It is tragic that the pandemic is killing more children – a lot more children – than usually die from the flu. It is nonetheless deducible from the CDC estimates that the pandemic is less dangerous to children than it is to adults and seniors.

Analysis of the Pandemic versus the Seasonal Flu

While the preceding analysis of the pandemic itself is based entirely on the CDC December 10 estimates plus census data, the comparisons with seasonal flu estimates are not nearly as crisp. The CDC’s methodologies for estimating the seasonal flu burden and its distribution among age cohorts are necessarily quite different from its methodologies for estimating the burden to date of the pandemic. So we are not comparing apples with apples.

But if it is approximately correct that about 90 percent of seasonal influenza-related deaths are in people 65 and older – as the CDC frequently reports – then the comparisons above between how the seasonal flu affects different age groups and how the pandemic so far affects different age groups should be approximately (but only approximately) on target.

The same is true for the comparisons below about overall seasonal flu severity versus pandemic severity so far. If it is approximately correct that about 5–20% of the U.S. population catches the flu in an average year, about 200,000 of them are hospitalized, and about 36,000 of them die, then the severity comparisons below should be approximately (but only approximately) correct as well.

| Cases: | There have been an estimated 47 million pandemic cases so far, 15.3% of the U.S. population of 308 million. The seasonal flu averages roughly 31 million cases per year, 10% of the 308 million total U.S. population. The CDC says the seasonal flu case attack rate ranges from 5% to 20%. At 15.3% and climbing, the pandemic is already near the upper end of the seasonal flu range. |

| Hospitalizations: | There have been an estimated 213,000 pandemic hospitalizations so far – versus roughly 200,000 hospitalizations in the average seasonal flu year. |

| Deaths: | There have been an estimated 9,820 pandemic deaths so far – versus roughly 36,000 deaths in the average seasonal flu year. |

Thus the number of pandemic H1N1 cases (15% of the population) from the start of the pandemic through November 14 was already getting close to the upper end of the CDC’s estimated range of seasonal flu cases (5% to 20% of the population). And that was at a point when the second wave was far from over. Through November 14, those cases had led to 106% as many hospitalizations as the average seasonal flu (213,000 pandemic H1N1 hospitalizations so far versus a seasonal average of 200,000 hospitalizations), which had led to only 27.3% as many deaths as the average seasonal flu (9,820 pandemic H1N1 deaths so far versus a seasonal average of 36,000 deaths). Remember: These comparisons are all methodological “apples and oranges.” But they are all we’ve got so far.

Here they are without any numbers: The pandemic has already sickened a lot more people than the seasonal flu average. Despite a lot more people getting sick, only slightly more people than the seasonal flu average have needed hospitalization. And with slightly more people hospitalized, far fewer people – less than one-third as many – have died.

If “mild” refers to the number of people who get sick, the pandemic is not milder than the seasonal flu average. In those terms it is already more severe than the seasonal flu average, and climbing. If “mild” means the percentage of the population or the percentage of sick people who end up dying, then the pandemic – so far – is significantly milder than the seasonal flu average.

But what’s happening in this pandemic to children under 18, and to adults 18-64, is certainly not mild, compared to the much smaller impact of the seasonal flu on those age groups.

What the Government Is Saying

The following three quotations are all from CDC Director Thomas Frieden’s December 10 press briefing, at which the CDC released the latest estimates. They are Dr. Frieden’s only remarks at the briefing bearing on the significance of the estimates.

The bottom line is that by November 14th, the day up to which those estimates include, many times more children and younger adults, unfortunately, have been hospitalized or killed by H1N1 influenza than occurs during a regular flu season….

What we have seen so far reiterates that people under the age of 65 are most heavily impacted by influenza. By November 14th, many times more children and younger adults, unfortunately, have been hospitalized or killed by H1N1 influenza than happens in a usual flu season. Specifically, there have been, we estimate there have been nearly 50 million cases, mostly in younger adults and children. More than 200,000 hospitalizations which is about the same number that there is in a usual flu season for the entire year. And, sadly, nearly 10,000 deaths, including 1,100 among children and 7,500 among younger adults. That’s much higher than in a usual flu season. So as we’ve seen for months this is a flu that is much harder on younger people and fortunately has largely spared the elderly until now….

In terms of comparison of this year’s flu with H1N1 influenza with seasonal flu, we know that it’s much milder for older people. It’s much less likely to result in death because older people are much less likely to get infected. But it has been a much worse flu season for people under the age of 65, particularly younger adults and children. The estimate we have – the estimate that we’re releasing here is not done in the same way that gives us the 36,000 estimate. That estimate is a different methodology. And will give a slightly larger number than this number would give. But if you were to compare, even though it’s not a directly applicable comparison, under 50 in that estimate, there are less than 1,000 deaths a year in age under 50. We didn’t break out in this – we’re not able to at this time, the 50 to 64 versus [under] 50. But a large portion of those adults are under 50. So it is really many times more severe in terms of severe illness and hospitalizations are several times higher for children and young adults as well in H1N1 than in a usual flu season….

Dr. Frieden’s comments convey the strong impression that pandemic risk is highest for children 0–17 and adults 18–50. As we have seen, the CDC’s December 10 data say that the pandemic is deadliest so far to the 18–64 age group, slightly less deadly to the 65+ age group, and least deadly to the 0–17 age group.

The vaccination public service announcements released by the Department of Health and Human Services on December 7 emphasize three groups: children, pregnant women, and young adults.

Here’s the text of one 10-second television PSA: “Children are especially at risk for the H1N1 flu virus. So get yours vaccinated. Learn more at flu.gov. Together, we can all fight the flu.”

Are children really “especially at risk” for the pandemic virus?

- If you think “especially at risk” means “more at risk than from the average seasonal flu,” then the statement is true.

- If you think “especially at risk” means “more at risk than their parents and grandparents,” then the statement is false according to the CDC’s estimates.

I don’t want to speculate on which message, the true one or the false one, the writers of this PSA meant their audience to hear. Either message would presumably help motivate parents to get their children vaccinated. But which message, the true one or the false one, will adults and seniors hear when they listen to the PSA, and how will that message affect their intention to get vaccinated?

And here is a line from a 30-second PSA distributed by HHS: “Kids run a higher risk of getting the H1N1 flu and developing serious complications.” What message are people in all age groups likely to get from the second half of that sentence – that children are likelier to have serious swine flu complications than older people (false) or that children are likelier to have serious swine flu complications than during an average flu season (true)?

The CDC website currently describes the U.S. government’s pandemic vaccine priority groups as follows: