Your inquiry focuses on how long it took the World Health Organization to acknowledge aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19.

The extent to which SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by fomites versus droplets versus aerosols affects many policies, especially policies relating to which non-pharmaceutical interventions are likely to prove most useful. To oversimplify: sanitize hands and surfaces to reduce fomites transmission; stay six feet away and wear cloth masks to reduce droplet transmission; improve ventilation and wear N95 respirators to reduce aerosol transmission.

Early on, as you know, there was a lot of attention to fomites, which experts and officials were reluctant to discourage despite virtually no evidence that fomites were a significant transmission mode.

By contrast, there were grounds for real uncertainty about the relative importance of droplets versus aerosols – basically big droplets that fall quickly to ground versus tiny droplets that remain suspended in air (airborne). But WHO’s communications were not uncertain. It emphatically attributed SARS-CoV-2 transmission to droplets. It denied the importance of aerosols until June 2020, when it started acknowledging very tentatively that maybe aerosols might be significant.

I read with interest your July 2020 Nature article, “Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne – but health advice has not caught up.” So I know you know all of the above already.

It’s now pretty clear that both droplets and aerosols are important in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Their comparative importance is still hotly debated, especially vis-à-vis what sorts of face coverings people should be encouraged to wear.

It’s worth noting that WHO’s slow acknowledgment of aerosol transmission ran in parallel with its equally slow acknowledgment of asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission. The two are linked to some extent. Symptomatic people may cough and sneeze out clouds of droplets, whereas infected people without symptoms don’t do that as often, though both breathe out aerosols. I wonder whether WHO would have taken note of aerosol transmission more quickly if it hadn’t been reluctant to concede the importance of asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission.

None of this is my area of expertise, of course; it’s just my broad summary of what the experts are saying.

In my field – risk communication – I want to make five generic points that I think are relevant to why WHO was slow to acknowledge the role of aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Vis-à-vis science, WHO sees its role as certifying the current expert consensus, not (usually) advancing new, tentative knowledge.

In the information ecosystem, we look to some institutions for early warning of potentially important possibilities, and to others for reliable summaries of the state of knowledge. WHO tries to be in the first group for some purposes – most importantly, alerting member states to emerging infectious diseases. But vis-à-vis science, it wants to be in the second group. It doesn’t usually advance tentative scientific hypotheses. Instead, it certifies the expert consensus.

When scientific knowledge is increasing or changing quickly, WHO communications are thus a lagging indicator. I think mainstream scientific understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission neglected aerosols in the early months. (The engineers and ventilation experts who had reason to know better weren’t virologists or epidemiologists, and weren’t in the conversation.) WHO’s neglect of aerosols, in short, echoed and certified the scientific mainstream.

When Lisa Brosseau wrote a commentary in CIDRAP News in early March 2020, urging more acknowledgement that transmission modes were highly uncertain – and drawing attention to the aerosol hypothesis – she got a lot of pushback. I fervently believe that we ignore (or sometimes censor) outlier expert opinion at our peril; I think the COVID-19 pandemic provides ample evidence of that.

Even so, insofar as WHO is concerned, this is at least arguably more a feature than a bug. Purveying outlier expert opinion probably shouldn’t be WHO’s role.

Like all too many in public health, WHO has trouble acknowledging uncertainty.

In a 2004 column entitled “Acknowledging Uncertainty,” I wrote:

Most people hate uncertainty. They’d much rather you told them confidently and firmly that A is dangerous or B is safe, C is going to happen or D isn’t, E is a wise precaution or F is a foolish one…. [T]he pressure comes from all sides: affected industries, politicians, regulators, your employer, your peers, your audience, and yourself. Everyone wishes you knew more, and everyone (consciously or unconsciously) pushes you to pretend you do. It isn’t easy to hold onto your uncertainty, to insist you’re not sure.

The external and internal pressure to sound certain is strongest, paradoxically, when uncertainty is greatest: in a terrifying crisis caused by a novel threat.

There are many downsides to sounding overconfident. Among them:

- Some people are instantly suspicious.

- Others rely on your confidence and later feel betrayed when you turn out wrong.

- You tend to believe your own overconfidence and become resistant to disconfirming evidence.

- Even if you accept disconfirming evidence, it’s harder to admit you turned out wrong.

- Dialogue with alternative views becomes more polarized.

WHO’s tweet of March 28, 2020 is a particularly bad example of this nearly universal mistake. The first sentence, which you quoted in your email to me, is unequivocal: “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” No uncertainty there! The capitalized “FACT” and “NOT” are the antithesis of uncertainty.

The second sentence is better: “The #coronavirus is mainly transmitted through droplets generated when an infected person coughs, sneezes or speaks.” Here, “mainly” suggests that transmission isn’t dichotomous, that by “NOT airborne” WHO means “mostly not airborne.” I think that’s what most of the experts WHO was listening to believed at the time.

Better, but still not good risk communication. If the second sentence started “Most experts believe…”, and if it included breathing with coughing, sneezing, and speaking, I’d have no quarrel with it. (I’d still object to the first sentence, of course.) Better yet: “So far, most experts tentatively believe….” And even better: “Although many experts in other relevant fields beg to differ, so far most experts in public health tentatively believe….”

Even when a public health information source resolves to acknowledge uncertainty, it’s a challenge to get the message across. Journalists tend to edit out the uncertainties or find a more confident source. Audiences do likewise. For uncertainty messaging to get through, it has to be proclaimed, not just acknowledged.

But anyone who starts a tweet “FACT:” obviously isn’t trying to convey uncertainty.

When expert knowledge and expert opinion change, WHO is reluctant to acknowledge the change.

Since WHO (perhaps wisely) sees itself as summarizing and certifying the current state of expert knowledge and opinion, it has a special obligation to let people know when expert knowledge and opinion have changed. Or to put the point less charitably: Since WHO is late to come to a conclusion, if it turns out to be the wrong conclusion WHO really needs to say so quickly.

Sometimes the change that needs to be acknowledged is a substantive shift: “We used to think X. Now we think Y.” Sometimes it’s a decrease in confidence or an increase in opinion diversity. “We used to think X. Now we’re not so sure, and some of us think maybe Y instead.” Sometimes it’s an increase in complexity. “We still think X. But now we realize sometimes Y too.”

WHO doesn’t do that very well. Nor do most other public health and scientific organizations. They are afraid of losing credibility by acknowledging that they got something wrong. As I have already noted, there is a connection between acknowledging uncertainty and acknowledging changes in expert opinion. FACT: It’s easier to tell people you changed your mind if you weren’t so cocksure to start with.

We’re really talking here about two failures, not one: being reluctant to change your mind, and being reluctant to tell people you changed your mind. The first is ordinary human confirmation bias; we all do it. I guess the second is human too, but it’s culpable. The two are hard to distinguish from the outside, of course. But sometimes you see the minutes of advisory committee meetings and the like in which participating experts flat-out say it to each other:

“We were wrong when we said X. We now realize the truth is Y.”

“Yes, but if we acknowledge that now, people will lose trust in us. And that will do more harm than the mistake itself is doing. So we’d better just stick to X.”

“I see your point. We’re committed now. Our credibility is at stake. We’ve got to keep saying X.”

And when organizations do finally force themselves to say Y, they often do so in the dead of night. As in your example of WHO on aerosol transmission, the webpage suddenly changes. It’s an evergreen page with the same old URL, just new content … and absolutely no text or icon or other signal to suggest the content is new. The most recent update date is often your only clue that something on the page has changed. Only the Wayback Machine can tell you what that webpage used to say.

This airbrushing of history sometimes goes even further – deleting past tweets that turned out false, for example, and denying you ever said what you said (at least WHO hasn’t done that vis-à-vis aerosol transmission). Other times the revisionism takes the form of excuse-making. “No, we weren’t wrong.”

- “The science changed.”

- “The virus changed.”

- “The media misquoted us.”

- “The public misunderstood us.”

- “We never said we were absolutely, totally certain.”

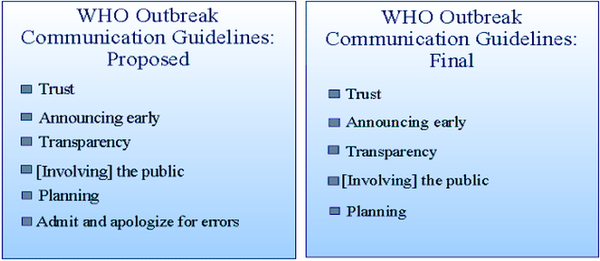

My wife and colleague Jody Lanard was hired to draft WHO’s 2005 “Outbreak Communication Guidelines.” Of the six guidelines in her draft, WHO member states adopted five. The one that WHO couldn’t accept, not even as aspiration, was to acknowledge and apologize for mistakes.

WHO didn’t want to come across as unduly alarmist yet again.

To make sense of WHO’s reluctance to acknowledge aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2, it’s important to realize how scary the idea of aerosol transmission is – and especially how scary it was in the early months of the pandemic, when we had reason to know COVID-19 was horrific and no reason to think we’d have spectacularly effective vaccines in less than a year.

If the virus spreads by fomites or droplets, there are obvious steps we can take to minimize our exposure: wash our hands, sanitize high-touch objects, stay a few feet away from other people, wear a face covering. But if the virus stays airborne, wafting around the room even after the infected person has left the room, we’re … well, not doomed, exactly, but in much deeper trouble.

If you want to scare the pants off people, then, you should welcome the chance to talk about aerosols. If you want to motivate calm precaution-taking, on the other hand, focusing on droplets or fomites would be a better choice.

Scientific truth obviously doesn’t depend on whether scientists seek to alarm or reassure their audience. But what scientists actually say – and even more, what public health professionals and public health agencies say – is greatly influenced by whether they’re trying to warn people they see as too apathetic, or to calm people they see as too frightened.

Public health professionals spend most of their working lives in warning mode. Their stock-in-trade is what I call precaution advocacy: trying to get apathetic audiences more attentive to health risks and more willing to take appropriate precautions (quit smoking, lose weight, get your kids vaccinated, put leftovers in the refrigerator before they spoil, finish your antibiotic course, etc.). But when a serious crisis arises, and people are finally taking a risk seriously, public health professionals often get alarmed at the public’s alarm. They mistakenly imagine that people are panicking or about to panic, and start trying to calm them down.

The history of the past two decades, moreover, is in some ways a history of pandemic false alarms. Bird flu (H5N1) was horribly deadly and looked like it might be The Big One, but so far it hasn’t acquired the ability to transmit efficiently human-to-human. SARS and MERS (coronavirus cousins of SARS-CoV-2) looked like they might go pandemic, but turned out to be controllable by conventional epidemiologic methods. Swine flu (pH1N1) really did go pandemic, but it was such a mild pandemic that the pandemic virus actually saved lives by outcompeting deadlier seasonal flu strains.

WHO and the rest of the public health establishment sounded the alarm about each of these pathogens – and each time they turned out wrong. Understandably and maybe even wisely, they began to worry about a reputation for alarmism.

The swine flu pandemic of 2009-2010 seriously damaged WHO’s reputation. The title of a 2010 website column Jody and I wrote tells the story: “The ‘Fake Pandemic’ Charge Goes Mainstream and WHO’s Credibility Nosedives.” When swine flu first emerged in Mexico and the U.S., WHO quite rightly warned that it looked bad; as swine flu spread, WHO quite rightly (though belatedly) declared it a pandemic; as swine flu’s mildness slowly became clear, WHO unwisely but predictably was exceedingly slow to change its messaging. A year into the pandemic, politicians in the European Parliament were accusing WHO of intentionally hyping a “fake pandemic” to help Big Pharma sell vaccines.

In the shadow of that history, it’s understandable that public health professionals in general and WHO in particular hesitated to sound the COVID-19 alarm too loudly. Part of that hesitation was their slowness to acknowledge aerosol transmission. Determined not to fall into the over-alarm trap yet again, they fell into the over-reassurance trap instead.

-

WHO’s policy goals influence which data and which conclusions it messages.

As I noted earlier, scientific truth obviously doesn’t depend on the policy goals of a scientist or science-based organization. But messaging does. Two of the biggest influences:

- Cherry-picking data that support the conclusions you want to highlight, and downplaying or omitting data that point in a different direction.

- Assessing data on a sliding scale of reliability and validity – that is, too easily trusting studies with conclusions you like, while finding methodological grounds to dismiss studies with conclusions you don’t like.

Some of this is unconscious, confirmation balance rearing its head once again. But some of it is intentional.

Public health organizations like WHO frequently encounter situations where telling the unvarnished truth seems likely to lead to outcomes that are bad for health. The unvarnished truth might scare people too much or too little. The unvarnished truth might reveal downsides of a precaution and thus discourage people from taking that precaution. Etcetera. In all such situations, public health professionals are forced to decide how much of the truth to trust the public with.

Faced with a choice between truth and health, public health professionals often choose health. They try hard not to lie. But with varying degrees of self-awareness, they intentionally mislead their audience about certain facets of the situation for the audience’s own good.

I have been thinking, writing, and talking about this truth-versus-health dilemma for decades. A good place to start is my 2016 article: “U.S. Public Health Professionals Routinely Mislead the Public about Infectious Diseases: True or False? Dishonest or Self-Deceptive? Harmful or Benign?” For COVID-19 examples, see this April 2021 article by Jad Sleiman, based chiefly on an interview with me.

If you were the World Health Organization in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, you didn’t want to raise the specter of deadly virus wafting through the air. You didn’t want to say anything that you thought might panic people into paralysis instead of motivating calm precaution-taking. You were worried about all those prior pandemic false alarms, and your own reputation for undue alarmism. And so you were all too likely to dismiss – even deny – emerging evidence of aerosol transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Copyright © 2022 by Peter M. Sandman