Public Health’s Single Biggest COVID-19 Risk Communication Failure

by Peter M. Sandman

Other articles on this website

about Wuhan coronavirus

risk communication

Especially relevant articles

on this website from

SARS, bird flu, swine flu, etc.

A reporter recently asked me what I consider “the single biggest communication failure” of public health experts and officials with regard to COVID-19. It took me a few weeks to think it through, but I now have a five-part answer to this question.

Part One: Public Health Over-reassures the Public

The most obvious, huge communication failure of public health professionals vis-á-vis COVID-19 was their failure to warn governments, companies, and the rest of us to prepare in January, February, and into March.

Almost from the outset, it was apparent to most experts that COVID-19 would probably keep spreading – that it was much likelier than not to go pandemic. But it wasn’t apparent at first how severe the COVID-19 pandemic would be. So the right messaging would have been about logistical and emotional preparedness for the hard time that might (or might not) be coming.

Despite knowing that a severe pandemic was a distinct possibility, public health experts and officials chose instead to reassure the public. Alas, to everyone’s subsequent dismay, they succeeded. They were worried about public panic. So they validated the public’s complacency – and with it, the complacency of everyone else – and left us incredibly unprepared.

The “us” they left unprepared includes most corporate leaders, who paid far too much attention to official claims that the risk was low – and far too little attention to their own risk matrices. Nearly every company of significant size has taken “enterprise risk management” onboard, and nearly every enterprise risk management effort incorporates a probability-by-magnitude matrix to help management identify risks worth mitigating. Those matrices teach that a risk whose magnitude is devastatingly high deserves increasing amounts of preparedness effort as its estimated short-term probability rises from very low to low toward moderate.

And to a large extent public health officials bought into their own over-reassurances. They, too, failed to prepare, and failed to convince their political bosses (and lower-level public health officials) to prepare.

Not content merely to reassure, some leaders went out of their way to attack the very idea of anyone being frightened enough to bother preparing. Some, including World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, initially said that fear of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was worse than the virus itself:

WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus) (February 28, 2020): “Together, we are powerful. Our greatest enemy right now is not the #coronavirus itself. It’s fear, rumours and stigma. And our greatest assets are facts, reason and solidarity.”

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (March 7, 2020): “We’re handling it and things are under control, right? Number one problem is hysteria and fear as opposed to the virus and I think government can either address that or compound it.”

What accounted for this failure to warn? As the quotations from Tedros and Cuomo make clear, the root of the problem was what I have called “fear of fear” – especially experts’ and officials’ unjustified concern that if they frightened people, the people they frightened would find the experience permanent and unbearable. Keeping company with fear of fear was “panic panic” – the panicky feeling on the part of many experts and officials that the public’s fear would escalate into panic.

But there was a more justified concern as well, experts’ and officials’ concern that they would be criticized for unduly frightening the public. I think public health professionals were afraid of being thought alarmist if COVID-19 fizzled or turned out mild. They had aggressively warned the world about a possibly disastrous bird flu pandemic, and it never happened; they had aggressively warned the world about a possibly disastrous swine flu pandemic, and it ended up less deadly than a typical flu season. In the wake of these two false alarms, this time they elected not to shout from the rooftops. Their warnings were sotto voce, easy to ignore. And their warnings stayed sotto voce even after it was clear they were being ignored.

To a lesser extent, some of public health professionals’ failure to warn was probably due to their fear of provoking stigmatization of Asians and Asian-Americans. It amazes me that Tedros could believe that fear and stigma are greater enemies than the coronavirus itself. But he has said it again and again, and I have to think he means it.

In those key early weeks, the main message from the public health establishment was that “the risk to people here in [wherever] is low.” This was technically true, since there weren’t yet a lot of COVID-19 cases in [wherever]. But public health professionals know that risk is supposed to be a forward-looking concept. In October, before the start of flu season but well into flu vaccination season, they would never say that the risk of flu is low. Focusing on the known current risk instead of the likely future risk allowed public health professionals to keep saying the risk was low for far too long.

In February 2020, if you were looking for it, you could find some public health messaging to the effect that the COVID-19 risk might not stay low, so now might be a good time to start preparing. But that was a comparative whisper. The shouted message was that the (current) risk was low.

And the implication of that message was that preparations and precautions were unnecessary, maybe foolish and alarmist, maybe even hysterical and panicky. So go about your business, go celebrate the Lunar New Year in large crowds, and don’t worry about stockpiling medicines or food or toilet paper. Don’t get unnecessarily fussed about this thing that might not even be a pandemic.

High-level government officials like New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio cooperated fully with propagating these sorts of over-reassuring messages to their citizens. (I’m picking on de Blasio because New York City quickly became the U.S. COVID-19 epicenter for the first few months of the pandemic.) Were there public health experts and officials privately warning de Blasio that these over-reassuring messages might turn out deadly? I can’t say. Were there public health experts and officials aggressively contradicting de Blasio, sounding the alarm to the New York City public? No.

Part Two: Public Health Panics and Overreacts

Pretty much everyone agrees that New York City became a disaster area because its government underreacted to the emerging crisis, failing until weeks too late to shut down mass events, close schools, announce social distancing policies, etc. Nearly everyone also agrees that precisely because it was slow to react before the virus had spread out of control, New York City’s government was wise to impose a near-total lockdown of the city, a radical solution to a disastrous situation. Governments in China and Italy were similarly wise to lock down Wuhan and later Milan (and their vicinities). Wherever the SARS-CoV-2 virus was already widespread and spreading exponentially, local lockdowns made sense – to slow the spread, keep hospitals from being overwhelmed (or further overwhelmed), and buy time for urgent, belated preparations.

But does that mean that lockdowns also made sense in places where the virus was not yet widespread? Most of the United States and much of Europe locked down at a time when more conventional, less extreme interventions might have sufficed.

Consider the measures that are now widely utilized in places that are successfully managing the pandemic: social distancing; masks where social distancing isn’t feasible, especially indoors; cancelation of mass events and maybe of schools; handwashing; widespread testing; contact tracing and quarantine; expanded hospital surge capacity; expanded supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE); sequestration of especially vulnerable populations; special precautions for nursing homes and other congregate settings; etc.

By the time New York City awoke to the COVID-19 danger, it was arguably too late for anything but lockdown. But wouldn’t these lesser (and economically less devastating) measures have worked elsewhere – instead of lockdown rather than after lockdown? Maybe even just some of these measures, if a few of the most difficult ones (like contact tracing) weren’t feasible?

Every pandemic plan I ever worked on or looked at, starting in 2004, emphasized the importance of responding quickly with what the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called “targeted and layered”  local non-pharmaceutical interventions to slow the spread of the virus. The interventions the writers of these plans had in mind were the sorts of interventions I just listed. I never saw a pandemic plan that contemplated telling everyone to stay home, locking down entire states and countries.

local non-pharmaceutical interventions to slow the spread of the virus. The interventions the writers of these plans had in mind were the sorts of interventions I just listed. I never saw a pandemic plan that contemplated telling everyone to stay home, locking down entire states and countries.

Instead of the targeted, layered, and local measures that all extant pandemic plans had recommended, we ended up devastating our economy with lockdowns even in places where the virus wasn’t widespread and hospitals weren’t crowded. Lockdowns in such places meant, among other things, that elective medical procedures were canceled; empty hospitals furloughed staff the same way empty restaurants did.

Even now, I am at a loss to explain how the U.S. public health profession suddenly came to the conclusion that a nearly national lockdown was the right response to SARS-CoV-2. China’s apparent success in suppressing the virus by locking down much of the country obviously played a key role. But I distinctly remember how shocked and disapproving most public health people seemed to be about China’s lockdown. Then came the disaster in northern Italy, with Milan following in the footsteps of Wuhan. Modelers at Imperial College London and elsewhere did their extrapolations and predicted millions of deaths unless extreme measures were adopted. New York City looked like it was following in the footsteps of Milan. And suddenly – it felt very sudden to me – lockdown was deemed the appropriate response even in places that showed no signs of following in the footsteps of New York City.

I realize there were outliers within the public health profession who said that such a widespread lockdown was an overreaction. What’s amazing is that they were outliers. Virtually the whole profession suddenly backed widespread and apparently indiscriminant use of a measure that no previous pandemic plan I’m aware of had ever even contemplated.

People are now saying that a number of southern and western states came out of lockdown too soon. Maybe so – though “too quickly” makes more sense to me than “too soon.” But at least as important, and almost universally ignored, is the possibility that these states went into lockdown too soon. If places with relatively little community transmission had tried more moderate interventions in March, especially while test capacity and contact tracing staff were ramped up, maybe they wouldn’t now face a decision about whether to lock down in August. And if they do need to lock down in August, at least they wouldn’t face a public whose tolerance for lockdown has been wastefully exhausted.

I’m just a risk communication expert, not an epidemiologist. I am not entitled to a professional opinion about whether widespread lockdowns were called for. But it looked to me in real time – and still looks to me today – like public health experts and officials panicked. They saw what happened in Wuhan, then Milan, then New York. They realized how badly they had underreacted to COVID-19. And very suddenly, without a lot of public explanation (much less public debate), they prescribed universal lockdown. What they didn’t prescribe is what all the pandemic plans prescribe: in places that need them, fairly extreme targeted measures like telling people to work from home, closing certain venues, and canceling mass gatherings; in places with less spread of the virus, less stringent measures. That’s the prescription I expected, the prescription I waited for.

The public health profession in the United States was shockingly slow to react to the threat of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. And then it overreacted.

I am a longtime opponent of diagnosing panic when people get frightened about some risk and start taking precautions, even excessive precautions. For decades I have pointed out that panic isn’t just feeling panicky, and it isn’t just taking precautions that may be unnecessary. By 2005, having learned the term from my psychiatrist wife and colleague Jody Lanard, I was writing that taking premature and arguably excessive precautions is a normal, healthy, and even useful “adjustment reaction” to a new risk – not panic. As I have written again and again, panic is “doing something harmful to yourself or others that you would never do if you were thinking straight, but you can’t help yourself because of out-of-control emotions.” By that definition, panic is an extremely uncommon response to crisis. People feel panicky and may take excessive precautions, but they rarely panic.

But by that definition, I think it is fair to say that in places without a lot of SARS-CoV-2 circulating, politicians and their public health advisors who ordered massive lockdowns panicked.

Please note again: My opinion that it was a mistake to lock down places with very little viral spread is a nonprofessional opinion. What I can confidently say as a professional is this: The lockdowns never got much public debate. There weren’t a lot of op-eds by public health professionals pointing out that broad-based lockdowns were a deviation from all prior pandemic planning, and wondering aloud if they were wise. There weren’t even a lot of op-eds explaining why an emerging consensus of public health professionals believed they were, in fact, wise.

Whether or not locking down most of the country was a public health mistake, certainly doing so with very little public discussion of the pros and cons was a risk communication mistake.

Above all, it was a risk communication mistake not to provide the public with a sustainable rationale for the decision to lock down so much of the country.

Part Three: Public Health Flubs the Rationale for Lockdowns – with Profound Implications for the Path Forward

I can see two rationales for lockdowns.

The first rationale: The virus is exploding already and we need to throw everything we’ve got at it right now. That was true in New York City, but false in many other places that were locked down anyway.

The second rationale: The virus will get here sooner or later; it might even be here already and not visible yet. Lockdown is the best way for us to buy time so we can prepare for what’s coming – update our pandemic plan; buy more PPE and testing supplies; expand our hospital surge capacity; hire more contact tracers; figure out which targeted, layered measures we should leave in place when we let up on full lockdown; etc. Unfortunately, in many places (certainly many places in the U.S.) the lockdowns remained in effect for months but the authorities frittered away those months without doing nearly enough to prepare. They were thus almost as unprepared to cope with explosive spread post-lockdown as they would have been pre-lockdown.

So how could public health professionals make the near-universal lockdowns not seem like they were a horrible mistake, devastating millions of lives to no purpose? Offer a third rationale: The lockdowns prevented infections and thereby saved lives.

I think public health professionals moved largely to this third rationale. Were they consciously trying to protect their reputations by making a bad policy look good? Were they unconsciously ginning up a post-hoc rationale for their panicky overreaction? I don’t know what was going on psychologically. What I do know is this: In the midst of nearly nationwide lockdowns that arguably weren’t needed and indisputably weren’t well-used, public health professionals found something about the lockdowns they could honestly praise, the fact that the lockdowns reduced COVID-19 case counts. They sounded increasingly absolutist about the importance of minimizing the number of cases at all costs, and thus increasingly skeptical about the wisdom of coming out of lockdown.

In doing so, they pointed the public away from the goal of living with the virus, toward the goal of beating the virus. That change from a pandemic management narrative to a pandemic suppression narrative continues to have profound policy implications as Americans try to think about the path forward.

Bear in mind that even though pandemics are global by definition, they wax and wane locally. So managing the COVID-19 pandemic really means managing the waxing and waning of local COVID-19 outbreaks and epidemics. (Epidemics are big outbreaks, basically.) Suppressing the pandemic, similarly, means getting the local transmission rate down near zero and keeping it there. “Keeping it there” is the main challenge. As many cities around the world are discovering, you might think you have suppressed the virus locally; then it re-enters or re-emerges and you must decide all over again whether to manage it or try to suppress it.

The question of whether, when, and how to reopen schools is a good example of the management versus suppression choice. Managing the pandemic (really the local outbreak/epidemic) means balancing the infection control risks of letting kids go to school against its educational, health, emotional, and economic benefits. Suppressing the pandemic (or the local outbreak/epidemic) means deciding that infection control must trump these other considerations. Whether or not to reopen schools is a tough question if we’re balancing competing priorities. If we’re minimizing transmission at all costs, on the other hand, the answer is easy: Don’t open the schools until it is “safe” to do so.

One of the most useful early commentaries on COVID-19 response was written by someone from outside the public health profession, Tomás Pueyo, an engineer and business executive. Entitled “Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance,” it was posted on March 19 on Medium, an unrefereed online publication. Pueyo accepted that for a brief period it might be necessary in some places to take very extreme, lockdown-like measures against the pandemic virus (the hammer). But thereafter, he said, the trick is to balance infection control with other priorities such as economic viability (the dance). When transmission levels are low, you raise the hammer, but not so high that hospitals are overwhelmed. If transmission levels creep up beyond the optimal balance you’re trying to maintain, you lower the hammer a bit, just low enough to restore the balance but hopefully not so low that New Normal life comes to a stop again. Raising and lowering the hammer in small increments is the dance. The increments, of course, are measures like opening or closing various kinds of businesses, permitting or forbidding various kinds of interactions, getting stricter or laxer in mask and social distancing requirements, etc.

Whereas New York City may have needed to lower the hammer all the way before it could progress to the dance, most other places might still have been early enough in their local outbreaks to just dance. If they weren’t ready to dance, as many weren’t, maybe a total lowering of the hammer wasn’t a bad way to buy them more time to get ready. If they’re still not ready – if they frittered away the time and didn’t prepare, or if their preparations failed – they might even need a second or third hammering. But sooner or later, we must all learn to dance.

The key distinction is between “dancing” with the virus and trying to suppress the virus. Suppression means aiming to nearly eliminate pandemic deaths by nearly eliminating pandemic infections. In a country as big and porous as the U.S. (unlike, say, New Zealand), suppression probably requires lockdown or something close to lockdown not just for a little while but for the duration. Such a sustained lockdown would mean economic devastation and manifold other disastrous effects on education, mental health, etc. No country can sustain that kind of damage for long, nor will its populace remain cooperative for long in the face of such devastation.

So a suppression strategy makes sense only if it probably won’t have to last long – that is, only if you confidently anticipate amazingly effective vaccines or medicines within months.

This is a crucial dilemma. Conventional wisdom says that it takes years to develop new vaccines and medicines against a previously unknown pathogen – and even then, they are likely to be only modestly effective, better at managing a pandemic than at suppressing one. But new vaccines and medicines against the SARS-CoV-2 virus are being developed at breakneck speed. When President Trump first said we could have a game-changing vaccine ready to deploy before the end of the year, most public health professionals considered the claim wildly optimistic, arguably dishonest. Now there are public health professionals (not to mention pharmaceutical executives) on television making roughly the same claim. And judging from stock market prices, investors believe the claim.

If the pandemic really might be nearly over early next year, it would be horribly wrong to let, say, an extra hundred thousand Americans die in the next few months just because we’re in a hurry to resuscitate our economy or get our kids back in school, much less to have a drink with friends. If we have just a few months of pandemic left, prioritizing infection control makes sense. Precisely because it will be brief, suppression is the right narrative.

But if the pandemic is going to be with us for at least another year or two, maybe more, suppression is a pipedream. The only sensible way to manage a long-term pandemic is to plan to “dance” with the virus, perhaps after a brief lockdown to give governments a chance to reduce transmission to fairly low levels, get their bearings, and prepare to dance – increase hospital surge capacity, build a contact tracing organization, stockpile more test supplies and personal protective equipment, etc.

Some European and Asian countries today are dancing pretty successfully. When their tests show intermittent small outbreaks, they restore appropriate precautions – sometimes even brief local lockdowns if they waited too long or if they’re being extra-cautious. Once they get an outbreak under control, they slowly relax some of the precautions again. When their case counts are very low, it may look from the outside, or even to their own publics, like these countries have successfully suppressed the pandemic virus – until the next outbreak shows that it’s just part of the dance.

But for countries like the U.S. that haven’t yet learned to dance and are still enduring disastrous case counts in many places, the dilemma is excruciating. It’s the same dilemma whether or not local conditions require at least a brief local lockdown. Should we try to stay locked down or nearly locked down in hopes of a pharmaceutical miracle sooner rather than later? Or should we try to learn to dance?

Obviously, nobody knows whether a pharmaceutical miracle will come true. I’m not convinced that most U.S. public health professionals really believe we will have miraculously effective vaccines and medicines in a few months – not just miraculously effective in principle, but universally available and widely accepted. I think they mostly expect the COVID-19 pandemic to be a marathon, not a sprint. I suspect they’re sounding optimistic about vaccines and medicines at least in part because they want to make a case for prioritizing infection control over everything else. And I suspect they’re lining up behind infection control as the top priority at least in part because that’s the only way to avoid admitting that such widespread lockdowns might have been a horrible mistake.

To understand the logic, consider this imaginary dialog:

| Q: | Why did we lock down places that didn’t have explosive outbreaks yet and didn’t use the lockdowns to get properly prepared? Didn’t that turn out to be a horrible mistake? |

| A: | No, it wasn’t a mistake. Lockdowns prevented infections and thereby saved lives. |

| Q: | Okay, so what do we do now? |

| A: | Keep preventing infections and thereby saving lives. |

| Q: | But we can’t do that forever! We need to educate our kids! We need to resuscitate our economies! We need to return to some semblance of normal life! |

| A: | Uh, they’re making wonderful progress on medicines and vaccines. |

Part Four: Public Health Abandons “Flatten the Curve”

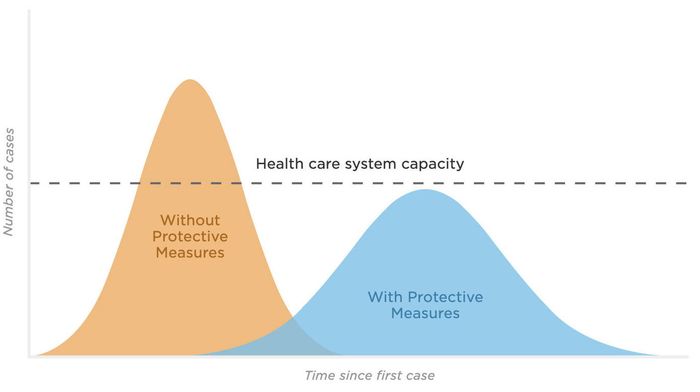

In the early weeks of lockdown, public health professionals talked a lot about “flattening the curve.” “Curves,” really – there are at least four relevant epidemic curves that need to be flattened – the curves of cases, hospitalizations, intensive care admissions, and deaths.

The basic concept behind flattening the curve is this: An unmanaged pandemic can infect so many people so quickly that hospitals are overwhelmed. As a result, people die who could have been saved in a functioning healthcare system – not just people with COVID-19, but also people with cancer, heart attacks, car crash injuries, etc. Flattening the curve doesn’t necessarily reduce how many people are infected. It just spreads out their infections. That keeps the healthcare system functioning, which saves lives.

A second benefit: Flattening the curve delays a lot of infections. Since treatment protocols and medicines are constantly improving, delay saves lives too. Your prospects of survival if you catch COVID-19 are significantly better today than they were a few months ago.

But the core goal of flattening the curve is to spread out infections so you keep the healthcare system functional. In the early weeks of lockdown, I kept seeing media stories in which public health professionals explained this. For a while the “flattening the curve” graph was everywhere you looked: the horizontal dotted line to indicate hospital capacity; the unflattened curve that went higher than the dotted line; the flattened curve that spread out the same number of cases so the dotted line wasn’t exceeded.

Then the use of the phrase waned, and the explanations pretty much disappeared, as did the graph. Try Googling “flatten the curve” + “same number of infections,” and you will see many examples from early in the pandemic, then fewer and fewer as time went on.

Not many commentaries have noted the decline of the “flatten the curve” narrative. One exception is Sean Trende’s May 3 analysis in Real Clear Politics:

But in the meantime, there seems to have been a subtle shift in the discourse. Some of this has been a refusal to update prior assumptions – some people seem to believe not much has changed since early March – but other analysts have subtly moved from “bend the curve” to what we might call “crush the curve.” Under the latter approach, rather than looking to keep hospitals from becoming overwhelmed, which raises the fatality rate, we should look to avoid all fatalities.

A successful lockdown flattens the curve just fine (whether or not the curve in a particular place really needed such a radical flattening). But when you come out of lockdown and start to resurrect your economy, the curve necessarily rises. The challenge is to flatten it again, at a level that’s higher than suppression/lockdown but still low enough for healthcare systems to stay functional.

Why higher than suppression/lockdown? Because societies can’t stay locked down forever. Flattening the curve doesn’t mean flattening it as low as possible. It might even mean flattening it as high as possible – as long as it’s low enough to keep healthcare systems functional – so you make the quickest possible progress toward eventual herd immunity (if immunity lasts), even if there’s never an effective vaccine. If you’re not aiming for herd immunity, you’re still trying to balance infection control against all your other priorities like jobs and education. Flattening the curve “as low as possible” is antithetical to balancing priorities.

Coming out of lockdown inevitably means increasing the number of infections and thus also the number of deaths. The goal is to minimize preventable deaths – that is, the deaths that a fully functioning healthcare system can prevent. (Lockdown postpones some deaths that won’t be preventable once you come out of lockdown.) So you keep the most vulnerable people as sequestered as you can. And you use measures less extreme than lockdown (masks, social distancing, hand hygiene, cancelation of mass events, testing, contact tracing, etc.) to keep the healthcare system functional and keep the economy mostly functional too.

Ground rules for how to dance

In short, flattening the curve isn’t an alternative to the dance. It’s a ground rule for how to dance.

Let me expand on this notion of ground rules for dancing with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. I think the following ground rules are all deducible from the “flattening the curve” concept:

- You want to get the curve as close to horizontal as you can get it. One key error to avoid is exponential spread – a curve that shoots upward like a rocket.

- There are going to be peaks and valleys. You want to keep those peaks and valleys small and gentle. Steep peaks are disruptive and risk exponential spread. Deep valleys are unnecessary and unsustainable.

- You don’t need to get the curve (ideally a horizontal line, remember) down to zero cases. That would be suppression, which is not a viable long-term goal.

- You do need to make sure the curve stays below the capacity of your healthcare system. That limit should rise as capacity improves – more beds, more personnel, more PPE, shorter hospital stays, etc.

To make sure the curve never exceeds healthcare system capacity, you need to maintain a cushion. The better your testing and contact tracing regimes, the less cushion you need.

- The toughest question is how low or high a curve to try to maintain. Lower means fewer illnesses and deaths, at least in the short term. So the lower the better. Except that higher means a stronger economy, more interpersonal contacts (including at school), and a more normal life; higher also means more progress toward herd immunity. So the higher the better, too.

- Science can help you achieve and maintain your curve (ideally horizontal) at the level you’ve decided you want. But science cannot tell you how to balance priorities to decide how low or high a curve to aim for. That’s about values, not science.

Pueyo’s dance metaphor was fairly widespread in the early weeks of lockdown, and the “flatten the curve” concept was omnipresent. Then they went missing. Instead of drumming this message incessantly, public health professionals joined in the much more seductive message that we should aim to prevent every infection we can possibly prevent, almost regardless of the collateral damage to the economy, to children’s education, to mental health, etc. Instead of dancing and flattening the curve, the dominant narrative switched to suppression.

Even in the early weeks of lockdown, it was hard to find explanations of flattening the curve that made the ground rules – or even most of them – clear. They were implicit, fuzzy. Once the narrative switched to suppression, of course, these ground rules weren’t just fuzzy. They were anathema.

I’ve already said why I think that happened. Most places didn’t need lockdown to flatten the local curve, and didn’t use lockdown to get ready to keep it flat. The only way to make lockdown not look like a horrible mistake was to switch to the suppression narrative: “We locked down to save lives.” And what follows from that: “We probably should have stayed locked down until we could open up without killing people. And if we’re killing people now, maybe we should lock down again. Certainly we shouldn’t reopen the schools until we can do so safely.”

I spent decades telling clients that safety isn’t a dichotomous concept. Of course we can’t open our schools “safely,” nor can we keep our children out of school “safely.” “Can we reopen the schools safely?” is the wrong question. Among the right questions are these:

- How much safety can we achieve as we reopen the schools, and at what cost?

- How much health damage are we willing to tolerate as the price of reopening the schools?

- How much educational and economic damage (and health damage too) are we willing to tolerate as the price of not reopening the schools?

- Given the full range of ways to reduce the infection rate, what alternative precautions are we willing to support so we can reopen the schools – for example, would we rather live with closed bars than with closed schools?

And if we’re serious about flattening the curve, here’s one key question I have never seen raised: How many additional hospitalizations will reopening the schools lead to, and is the healthcare system able to cope with this additional load? Does this question sound heartless to you? If so, that’s how far our understanding has strayed from flattening the curve.

Optimism versus pessimism

At the most basic level, the battle between these two narratives is the battle between optimism and pessimism. (Those who are skeptical about the prospect of an imminent pharmaceutical miracle see it as the battle between self-deception and realism.)

The optimistic (self-deceptive?) narrative is suppression = containment = prioritize infection control over everything else = end the pandemic. I call it optimistic because it is grounded in the unspoken assumption that it’s economically and emotionally feasible to suppress the pandemic and keep it suppressed until, somehow, the crisis is over. The pure version of this narrative, if it were spoken, would sound something like this:

We need to do everything we can to stop the spread of this virus – whatever it takes to bring the number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths down near zero and keep it there. If opening bars or opening schools means more infected people, close the bars and schools and keep them closed. If lockdown is the only way, then lock down – and stay locked down until we have a vaccine or until the pandemic ends by some other means. Open up only to the extent that we can do so without seeing significant numbers of new infections. The only pathway to restoring our economy and our way of life is first to win the war against the pandemic.

The pessimistic (realistic?) narrative is flatten the curve = dance = balance infection control against other priorities = manage local outbreaks in order to manage the pandemic. It, too, is grounded in an unspoken assumption: the assumption that this pandemic entails a great deal of unavoidable suffering, and that misguided efforts to minimize infections at all costs will only exacerbate the suffering. Here’s how the pure version might sound if it were spoken:

This is a horrible time. People are dying, and many more will die. Even the healthy are suffering. Many of our jobs are gone. Much of our way of life is on hold. All we can do is bear it, get through it, and try to avoid unwise decisions that would make things even worse. We don’t know when or how the pandemic will end. Until it ends, we need to keep our economy going, keep our hospitals functioning, keep our most vulnerable people protected, keep our masks on, and keep a reasonable distance from each other. Above all, we need to keep a delicate balance between fighting the pandemic and sustaining everything else we hold dear, as we ride out the next few very bad years.

It was never in the cards for public health professionals to say outright that “this is a horrible time” and we have no choice but to “ride out the next few very bad years.” But that level of pessimism (realism?) is the implicit prognosis when a society settles for flattening the curve instead of resolving to suppress the pandemic.

That level of pessimism (realism?) is also an implicit – and sometimes explicit – assumption in every pandemic plan I have ever seen. The plans typically consider a range of pandemic scenarios, including some more severe than COVID-19. They are plans for getting through a pandemic, not for ending one.

So a few weeks into lockdown, when U.S. public health professionals stopped talking much about flattening the curve and moved toward a suppression narrative instead, they weren’t just building a case that lockdown hadn’t been a horrible mistake. They were also building a case for optimism: a case that the COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t have to be a horrible time – and that if it is a horrible time, that must mean we’re doing something wrong.

It’s a weird kind of optimism, though. The optimism of the political right is much more straightforward (and straightforwardly self-deceptive): “We can quickly and safely rebuild our economy, open our schools and bars and everything else. Pandemic, what pandemic?” The optimism of public health professionals – that it’s feasible to suppress the pandemic with sustained, extreme non-pharmaceutical interventions – is accompanied by an enormous emphasis on the known and unknown risks of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. I’m reading lots of news stories right now about teachers beseeching the powers-that-be not to make them go back to school. I see the special pleading, the political posturing, the anger, etc. But it’s clear as well that many teachers, even young ones with no comorbidities, are genuinely terrified for their own health, as well as their families’ health and their students’ health.

I think it’s optimistic for public health professionals to suppose that we can suppress the pandemic virus and keep suppressing it until the crisis is over. The messaging that supports that optimistic supposition is explicitly optimistic about some things, especially the prospects for an effective vaccine. But public health messaging is anything but optimistic about the risk of catching COVID-19.

That risk is genuinely high, obviously. As I write this, the U.S. death toll has topped 150,000. Reality is scary enough. But a lot of public health messaging is even scarier – implying an unrealistically high probability of getting infected if you don’t take every prescribed precaution to heart, and an unrealistically high probability of a serious and perhaps fatal illness if you’re infected. A lot of the messaging dwells on the sickest victims, for example, or on those with the longest-lasting illnesses or the most upsetting symptoms or the weirdest pathways to infection. It’s not just that suppressing the pandemic is feasible, we are taught. Suppressing the pandemic is essential, because catching COVID-19 is terrifying and totally unacceptable, and all too likely unless we take every available precaution. Other priorities simply don’t count right now.

Signs of hope

I don’t want to overstate my case (especially since I am critical of public health professionals for so often overstating theirs). I’m being reductionist and probably unfair when I suggest that public health professionals abruptly “switched” their COVID-19 narrative from dancing with the virus and flattening the curve to suppression. The change was more gradual than I’ve made it sound. And in many cases, perhaps most, it wasn’t as extreme as I’ve made it sound – more an evolving change in emphasis than an abrupt switch from one pure narrative to its opposite.

Also, impressions and anecdotal evidence aren’t dispositive. I don’t have a good quantitative content analysis of public health professionals’ COVID-19 messaging.

Moreover, my impressions are beginning to shift a little. Toward the end of July I started seeing a few more public health professionals than in past months acknowledging in media appearances – on some channels more than others – that we need to learn to live with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, not keep destroying our economy trying to suppress infections.

I hope and believe this shift is real. But it is tentative and delicate. Living with the virus is still a minority position within the public health establishment. Oftentimes public health professionals who talk about living with the virus are immediately blasted by others accusing them of not caring about the lives of children or seniors or people of color.

Paradoxically, I think the shift from a suppression narrative back toward living with the virus is nurtured by the fact that several states seem not to have learned to live with the virus, opening up too quickly and hesitating too long as cases and then hospitalizations and then deaths spiked exponentially. That has freed some public health professionals to say, yes, living with the virus without overwhelming hospitals is the goal – and when a state blows that goal by opening up too quickly without enough hospital capacity, testing capacity, and contact tracing capacity, and when too many of the state’s residents fail to take basic precautions like social distancing and mask-wearing, the state may just have to back up and lock down at least partway, then try for a better balance next time.

Toward the end of July, some U.S. states let the curve – the numbers of cases, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and deaths – rocket almost vertically upward. I almost wrote “upward again.” But most of these states had relatively low COVID-19 incidence before they locked down. The exponential growth they saw in July was their first wave, not their second. In response, the concept of flattening the curve is making a bit of a comeback.

The suppression mantra still dominates, especially in discussions of school reopening. But maybe at least some public health professionals are starting to try to teach us how to dance.

Part Five: Public Health Insists It Should Be in Charge

Public health professionals’ prioritization of infection control over everything else wouldn’t matter so much if they were just one important voice among several.

The essence of the “dance” metaphor is finding a balance between infection control and other priorities, such as sustaining a viable economy – between saving as many lives as possible and saving as much of our way of life as possible. (Both goals should include keeping our healthcare system functioning well under stress.) Economic and health priorities are intertwined, of course. The health impacts of lockdown and economic devastation are huge: depression and suicide, addiction, domestic violence, etc. Poverty and chronic anxiety are known killers. It is equally true that you can’t resurrect the economy if people are afraid to shop or go to work. So managing the COVID-19 pandemic is crucial to economic revival, and reviving the economy is crucial to public health.

The public health establishment has shown remarkable insouciance about economic devastation, even the health effects of economic devastation. Most public health professionals have at least paid lip service to the desirability of resuscitating the economy, but far too many have insisted that the only path to a sustainable economic recovery is to defeat the SARS-CoV-2 virus – defeat, not just manage. It is comparatively unusual to find a public health professional urging, seeking, or even mentioning a balance between COVID-19 and other priorities, especially economic priorities.

That wasn’t true a few months ago, back before suppression replaced “flatten the curve” as the dominant narrative. Back then, public health professionals tried to explain that a flattened curve might still mean the same number of illnesses, just spread out over a longer period of time. Fewer people would die if the healthcare system wasn’t overwhelmed. But barring a miracle, people would keep getting sick, and some of them would die, right up until we either invented an effective vaccine or achieved herd immunity the hard way, with illnesses.

Look again at the “flatten the curve” graph, typical of the graphs that were widespread for a while. As the graph implies and as good graph explanations made explicit, the goal is a flattened curve that stays below the dotted line – not necessarily way below, wasting unused hospital capacity, just enough below to keep hospitals functional. Lower than that (via lockdowns and delayed reopenings) would postpone too many people’s infections for too long, delaying progress toward herd immunity (if immunity lasts) and doing unnecessary damage to the economy.

In short, balance was implicit in the “flatten the curve” narrative, and explicit in the clearest “flatten the curve” explanations. Balance got lost when the narrative shifted from “flatten the curve” to suppression. Now the narrative may be beginning to change a second time, back toward balance. A number of states look like they did a bad balancing job as they came out of lockdown. In explaining what they did wrong, some public health professionals have started sounding more sympathetic to the quest for the right post-lockdown balance.

But for the most part, still, public health professionals remain focused on the single goal of minimizing COVID-19 infections and deaths, not on balancing that goal against other priorities.

At the same time, public health professionals have also insisted that their advice should prevail in government and individual decision-making. In other words, they aren’t saying “We’re focused exclusively on COVID-19, but of course you have a broader view and must balance our advice against other priorities.” Instead they are saying, in essence, “We’re focused exclusively on COVID-19 and you must be too.”

The widespread adoption of the suppression narrative over the flattening-the-curve narrative is persuasive evidence that public health professionals are winning this battle on behalf of prioritizing infection control over everything else (except perhaps protest marches they support). So is the frequency with which government officials insist that they are “following the experts.”

Of course a government official who ignores public health advice is irresponsible. But in my opinion so is an official who follows that advice slavishly, without balancing it against other priorities. We’re seeing some of each in the U.S. today. But except on the political right, officials are far more frequently criticized for ignoring public health advice than for ignoring other priorities. So whether or not officials are actually doing everything the experts advise, they virtually always claim that they are.

I hate it when officials claim to be adhering strictly to “The Science.” COVID-19 science keeps changing and is hotly debated. Moreover, the key pandemic management questions go far beyond science. “How safe is safe enough?” isn’t a scientific question. Neither is how best to balance saving the most lives and saving the most of our way of life. These are political questions in the best sense of the word – questions officials need to answer with due deference to the interests and even the opinions of the body politic (that is, the public).

Of course officials should listen to scientists. But they shouldn’t be giving scientists their proxy. And if they’re not giving scientists their proxy, if they’re quite properly doing their best to balance infection control against other priorities, they shouldn’t evade accountability for their balancing efforts by pretending that they’re “following the experts.”

In recent weeks I have watched President Trump voice heated disagreements with some of his key scientific advisors with regard to COVID-19 – with Dr. Tony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health and with the entire U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Not surprisingly, the public health profession has lined up behind Dr. Fauci and the CDC. They’re right to mistrust both the president’s ability to hear what his scientific advisors are telling him and his ability to balance that advice against other priorities. A lot of governors and mayors of both parties have also shown themselves incapable (though not as incapable as Trump) of absorbing expert advice and finding a wise balance between infection control and other priorities. At the same time, the president isn’t wrong that Dr. Fauci’s advice and the CDC’s advice have sometimes seemed more oriented to suppression than to dancing with the virus.

Like nearly everything else in the U.S. today, pandemic response has become polarized. All too often, those on the left want to give public health professionals their proxy, joining in the suppression narrative and its dire implications for economic revival. All too often, those on the right adopt the opposite extreme, rejecting even commonsense infection control recommendations with negligible economic downsides, such as mask-wearing.

The United States is behind most of Europe and Asia in learning to manage local SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and epidemics – in Pueyo’s terms, learning to dance with the virus. I am hopeful that we will get there eventually. I’m not sure how. Maybe public health professionals will abandon the suppression narrative and revert to flattening the curve. Maybe political leaders will learn to listen attentively to public health professionals and then balance public health priorities against other priorities. Maybe the general public will listen to both extremes and find their own balance – or stop listening to both extremes and find their own balance. One way or another, we will learn to dance with the virus. We will have to; it isn’t going away. Either that, or the optimists will be proven right, we’ll soon have spectacularly effective vaccines and medicines, and we won’t need to dance after all.

Summary

My thoughts about public health professionals’ single biggest COVID-19 communication failure have turned into a five-part sequential answer:

First they underreacted, over-reassured, and left us unprepared.

Then they overreacted and unnecessarily locked down far too many of us, while still not ramping up preparations sufficiently to be ready to manage lower levels of transmission when we emerged from lockdown.

Then they justified the lockdowns by telling us that infection control trumps all other priorities, adopting a suppression narrative instead of teaching us how to balance priorities and “dance” with the virus by means of relatively small tightenings and loosenings of social distancing interventions.

As part of their defense of lockdowns, they abandoned the “flatten the curve” explanation, urging instead that suppression – minimizing COVID-19 transmission as much as possible – should be the paramount goal, not just keeping the infection level within the capacity of the healthcare system.

Meanwhile, they kept insisting that their advice was grounded exclusively in “The Science” and that political leaders and the general public should adhere exclusively to that advice, contributing to the polarization of pandemic response.

I’m sure of the first point. The other four are debatable opinions.

Copyright © 2020 by Peter M. Sandman