In October and November 2015, I drafted an article about how the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) handled its October 26 announcement that processed meats are a known human carcinogen. The article focused on the distinction between the seriousness of a risk (how bad is it?) and the quality of the evidence about that risk (how sure are you?); on how IARC fudged that distinction; and on the risk communication issues raised when a source like IARC leaves a misleading impression without actually saying anything untrue.

The media and the public soon lost interest in the carcinogenicity of processed meats, and I lost interest in completing the article. But the generic issues are important, and IARC’s processed meats announcement was similar to many other IARC announcements . In the months that followed, I occasionally mentioned my incomplete draft, and sent it to people who expressed interest in seeing it.

Most recently, on June 17, 2016, I sent it to Science reporter Kai Kupferschmidt, as part of my response to an email he had sent me seeking comment for a story he was writing [subscription required] on a new IARC announcement about the possible carcinogenicity of coffee and very hot beverages.

Since I have decided to post my response to Kai’s email, I am also posting this incomplete draft that was attached to my response. I have edited out most of my notes to myself about things I intended to add or change, but left in a few such notes that I thought might be worth reading.

On October 26, 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a subsidiary of the World Health Organization, announced that processed meats (bacon, sausages, ham, hotdogs, and even smoked turkey) are a known human carcinogen.

In the same announcement, IARC said that red meats (beef, pork, lamb, etc.) are a probable human carcinogen. But in this risk communication assessment I’m going to stick to what IARC said about processed meats.

Interest in the announcement petered out quickly. Meat industry sources claimed little short-term impact on sales. It’s too soon to tell what the long-term impact, if any, will be.

But the announcement raises some generic risk communication issues worth exploring in detail. One issue in particular will preoccupy this assessment. Assume you’re trying to warn the public about a health risk that you’re quite certain is genuine. Is it okay to make that risk sound bigger than it actually is, if you can do so without lying? That’s what I believe IARC did in its processed meats announcement. It’s not an unusual thing to do. This is in fact a persistent dilemma for government agencies, activist groups, and anyone in the precaution advocacy business: Are technically accurate but intentionally misleading warnings acceptable or not. I’m not going to prescribe an answer to this thorny question. But to help readers figure out their own answers, I want to examine exactly what IARC did.

How bad is it? How sure are you?

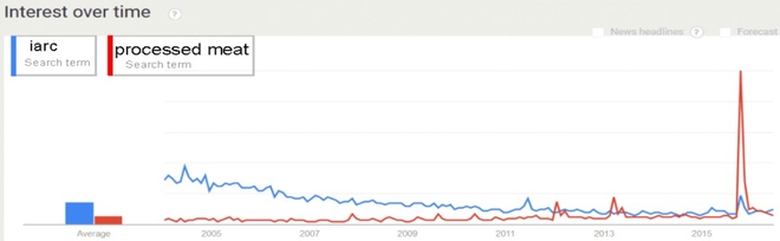

For at least a few days after the announcement, Google searches for “IARC,” which had been slowly declining since 2005, made a partial recovery. And Google searches for “processed meat” briefly soared as worried consumers checked out the new information.

Source: Google Trends

Except it wasn’t new information. The link between processed meats and cancer has been widely discussed at least since the nitrites controversy of the 1970s. The only thing new in October 2015 was that IARC took another look at the accumulated research literature and decided the evidence linking processed meats and cancer – especially colorectal (bowel) cancer – was strong enough to justify saying that processed meats constitute a human cancer risk – with no “probably” to weaken the claim. Plenty of others had already reached pretty much the same conclusion from pretty much the same evidentiary base. But now IARC was putting the World Health Organization imprimatur on the widespread conventional wisdom that processed meats are bad for you.

IARC didn’t say that processed meats are very bad for you. It just said it was very sure that processed meats are at least a little bad for you. Very sure. Not very bad.

The most important risk communication issue the IARC announcement raises is the confusion of these two questions: “How bad is it?” versus “How sure are you?” Both questions are obviously important, but they’re just as obviously not the same question.

IARC is dedicated exclusively to the second question, “How sure are you?” Following its establishment in 1965, IARC was bombarded with requests that it publish a list of known and probable human carcinogens. Which foods, industrial chemicals, occupations, etc. are known to be cancer risks to humans, it was asked. Which are suspected? Which if any have been cleared? So IARC started putting together expert “Working Groups” to assess the quality of the evidence that X is a human carcinogen, and then assign X to one of five categories.

Below are the names and descriptions of the five categories, the number of “agents” (substances or activities) that IARC says it has so far put into each category, and my own selection of examples of agents IARC has put into that category:

| Category | Description | # of agents | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Carcinogenic to humans | 118 | Arsenic, alcohol, asbestos, benzene, cabinetmaking, estrogen therapy, silica (sand – when inhaled), sunshine, tobacco |

| Group 2A | Probably carcinogenic to humans | 75 | Shift work (circadian disruption), trichloroethylene, ultraviolet radiation, wood-burning fireplaces |

| Group 2B | Possibly carcinogenic to humans | 288 | Aflatoxin, carpentry, chloroform, coffee, gasoline, lead, magnetic fields (extremely low frequency), mobile telephones |

| Group 3 | Not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans | 503 | Caffeine, chlorinated drinking water, crude oil, fluorescent lighting, fluorides in drinking water, saccharin, talc, tea |

| Group 4 | Probably not carcinogenic to humans | 1 | Caprolactam (that’s the only one, and I don’t know what it is either) |

IARC’s signature activity is the publication of monographs reviewing the evidence why a particular substance or activity belongs in one of these five categories. Volume 114 of the IARC monograph series puts processed meats into Group 1 and red meats into Group 2A.

The full monograph isn’t yet in the IARC website repository. But on October 26 IARC published a two-page summary ![]() in The Lancet Oncology and issued a news release

in The Lancet Oncology and issued a news release ![]() on the results.

on the results.

Just a quick look at my examples for Group 1 – the new home for processed meats – tells you that commentators who wanted to make eating a baloney sandwich sound suicidal could accurately point out that baloney is now in the same cancer-causing category as tobacco, while those who wanted to make it look benign could correctly note that IARC considers it equivalent to sitting on the beach in the sun (a carcinogenic twofer!).

It is worth noting that when IARC puts an “agent” in Group 1 it isn’t necessarily claiming there’s no room for disagreement that that agent is a human carcinogen. IARC’s Working Groups make their decisions by majority vote. Only 15 of the 22 experts on the Volume 114 Working Group voted to assign processed meats to Group 1; the other seven either abstained or preferred a different category.

Why? As is typically the case, the research literature they reviewed is full of anomalies and question marks. Some of the methodologically best processed meat cancer studies failed to find a significant effect. And all the studies are vulnerable to methodological criticism. Assessing human carcinogenicity is hard: Animal studies may or may not apply to humans, while human studies can’t ethically randomize which people get which doses.

Even though the phrase “known human carcinogen” gets plenty of use to describe the Group 1 agents, nothing is ever irrevocably “known” in science – especially a science as methodologically challenging as this one. To its credit, the IARC webpage on the classification system urges readers to pay attention to a monograph’s publication date, stressing: “Significant new information might support a different classification.” In other words, it wouldn’t shake the edifice of science – or even the IARC edifice in Lyon, France – if processed meats turned out not to be a human carcinogen after all.

It wouldn’t be a shock. But it would be a surprise. While meat industry scientists rightly insist that the data are far from ironclad and the decision was far from unanimous, it’s not really debatable that most experts think eating processed meats increases your risk of colorectal cancer, and maybe some other cancers as well. The experts aren’t completely sure that processed meats are a human carcinogen, but they’re sure enough that 15 out of 22 of them voted for Group 1, the “pretty damn sure” category.

The main problem here isn’t the “How sure are you?” problem. The main problem is that many news stories about the announcement left the impression that IARC was saying it had new evidence that the processed meat cancer risk is pretty damn big – whereas all IARC was really saying was that it had reviewed all the old evidence and decided it was pretty damn sure that the processed meat cancer risk existed; that it was at least a little risk, not no risk at all.

And for me as a risk communication expert, the main problem is that I’m pretty damn sure the misunderstanding was intentional on IARC’s part.

As far as I can tell, IARC’s two October 26 communications about the cancer risk of processed meats, the Lancet article and the news release, didn’t say anything false. I have no quarrels at all with the Lancet article. But I believe the news release was written to be misunderstood.

I can’t find a lot of news stories – any, in fact – that flat-out get the key facts wrong and mistakenly claim IARC has just discovered processed meats are horribly dangerous. The shorter stories simply say what IARC said – that the agency has now concluded that processed meats give people cancer. The longer stories usually include contextual information from sources other than IARC – often other cancer experts explaining that we have long suspected processed meats were carcinogens; or meat industry spokespeople explaining that processed meats have nutritional benefits and are part of a balanced diet, and that IARC says all sorts of things we love or can’t avoid give us cancer. Most importantly, the longer stories usually do some kind of risk comparison – typically explaining that while processed meats may be as definite a cancer risk as cigarettes, they are nowhere near as big a cancer risk as cigarettes.

A surprisingly large number of stories actually suggest that the IARC announcement is misleading. In fact, I can find more stories by reporters who believe the announcement is misleading than stories by reporters who seem to have been misled.

Nonetheless, I agree that the announcement is misleading. Moreover, I think the stories most reporters wrote are misleading. I think any story that starts by saying the World Health Organization’s cancer research arm has just announced that processed meats give you cancer is going to leave the impression that the risk is big, bigger than the experts have previously believed – perhaps even if the story explicitly debunks the claim that processed meats are horribly dangerous. IARC never actually makes that claim. It doesn’t have to make that claim in order to leave that impression. And I think IARC knows exactly what it’s doing.

Deconstructing IARC on processed meats

To understand IARC’s risk communication goal and strategy, let’s look at the news release ![]() . That’s the document that most reporters relied on, and that IARC presumably intended them to rely on.

. That’s the document that most reporters relied on, and that IARC presumably intended them to rely on.

The entire release runs only nine paragraphs. The first four are about the findings, the carcinogenicity categories to which red meats and processed meats were assigned. Only one of the four focuses on processed meats. It is unambiguous: “Processed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1), based on sufficient evidence in humans that the consumption of processed meat causes colorectal cancer.” Nothing so far about how much cancer processed meats cause. True to the IARC mission, the focus is on the quality of the evidence (“sufficient”) that processed meats are a human carcinogen.

In the eighth paragraph, the release goes into a bit more detail on that evidence: “The IARC Working Group considered more than 800 studies that investigated associations of more than a dozen types of cancer with the consumption of red meat or processed meat in many countries and populations with diverse diets. The most influential evidence came from large prospective cohort studies conducted over the past 20 years.”

That leaves Paragraphs 5, 6, 7, and 9 – all of which diverge from the “How sure are you?” question to address, directly or indirectly, the “How bad is it?” question. Here they are:

- The consumption of meat varies greatly between countries, with from a few percent up to 100% of people eating red meat, depending on the country, and somewhat lower proportions eating processed meat.

- The experts concluded that each 50 gram portion of processed meat eaten daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%.

- “For an individual, the risk of developing colorectal cancer because of their consumption of processed meat remains small, but this risk increases with the amount of meat consumed,” says Dr Kurt Straif, Head of the IARC Monographs Programme. “In view of the large number of people who consume processed meat, the global impact on cancer incidence is of public health importance.”

- “These findings further support current public health recommendations to limit intake of meat,” says Dr Christopher Wild, Director of IARC. “At the same time, red meat has nutritional value. Therefore, these results are important in enabling governments and international regulatory agencies to conduct risk assessments, in order to balance the risks and benefits of eating red meat and processed meat and to provide the best possible dietary recommendations.”

I see no problem with Paragraph 5. It just says that countries vary in how much meat they eat. Of course IARC might have added that the countries that consume more meat tend to be healthier and wealthier than the countries that consume less, rubbing in the reality that meat is a source of nutrition and a benefit of affluence, not just a cause of cancer. Still, the meat/cancer link obviously matters more in countries that eat more meat, and there’s nothing wrong with IARC noting that there is wide variation, thereby implying that its warning is aimed chiefly at heavy meat-eating countries like the U.S.

Paragraph 6 is much more problematic. It constitutes the only information in the release about the size of the cancer risk from processed meats. (The release has no information at all about the size of the cancer risk from red meats.) “The experts concluded that each 50 gram portion of processed meat eaten daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%.” Just about every news story I looked at used this quote, or at least this fact. What’s wrong with it? A lot:

- The paragraph assumes that the dose-response curve for processed meats is linear: an 18% colorectal cancer increase for every 50 grams, starting at zero and continuing to infinity, with no floor (if you eat that little, it’s harmless) and no ceiling (if you eat that much, more won’t add to your risk). That goes way beyond the evidence.

- The paragraph doesn’t explain in lay terms how much 50 grams is. So reporters had to make the translation. But not necessarily correctly. I saw equivalencies ranging from two strips of bacon to six.

- The paragraph commits the cardinal risk communication sin of dwelling on relative risk and ignoring absolute risk. An 18% increase in a big risk matters an awful lot more than an 18% increase in a small risk. In the U.S., lifetime colorectal cancer risk is about 4.5%; an 18% increase in relative risk would mean an increase in absolute risk from 4.5% to 5.3%. In other words, eating 50 grams of processed meats per day has a 0.8% absolute risk of causing colorectal cancer. That’s almost one-in-a-hundred – by no means tiny in a world where one-in-a-million cancer risks sometimes get regulatory attention. But 0.8% is not 18%.

- The paragraph fails to note that, even purely in relative risk terms, an 18% increase isn’t such a big deal. By contrast, cigarette smoking increases a smoker’s lifetime lung cancer risk by 1,500% to 3,000%, depending on how much he or she smokes.

- The paragraph has no risk comparison, neither quantitative nor qualitative. Is my processed meat consumption probably one of my bigger cancer risks or one of my smaller cancer risks? Should it soar to the top of my worry agenda or stay down about where it was yesterday?

- Above all, the paragraph is off-topic. It’s explicitly about the size the risk, not the quality of the evidence. Of course studies of processed meat cancer risk invariably estimate the size of the risk; that’s usually the main thing they’re interested in. But that’s not supposed to be what IARC is interested in.

Paragraphs 7 and 9 are quotations from IARC officials. Neither quotation is in the Lancet article, and I assume that neither will be in the monograph either. IARC put them in the release to help journalists write more interesting stories.

Dr. Straif in Paragraph 7 seems to be responding to the implication in Paragraph 6 and throughout the release that the risk of processed foods must be big (or why is IARC making a big deal about it?). So Dr. Straif flat-out says the individual risk is small. It would have been helpful if he had continued that thought, perhaps by pointing out how much less dangerous processed meats are than cigarettes. Instead, he feels compelled to add a “but” – that the individual risk, which he just said was small, “increases with the amount of meat consumed.” And even though the individual risk is small, he concludes, “the global impact” is important because so many people eat meat.

And Dr. Wild in Paragraph 9 passes the buck. Red meats and processed meats are bad for you, he says. But they’re also good for you (at least red meats are; he doesn’t commit himself on the nutritional value of processed meats). That’s why regulatory agencies have to balance risks against benefits and decide for themselves what “the best possible dietary recommendations” should be, bearing in mind that the data “further support current public health recommendations to limit the intake of meat.”

Both quotes look to me like half-hearted efforts to counterbalance the likely effect of the rest of the release, which is to suggest to reporters and their audience that processed meats (and probably red meats) are a serious health problem. Dr. Straif manages to say the risk is small; Dr. Wild manages to say meats have nutritional value. But both experts rebalance their balancing quotes to underline – not undermine – the main impression given by the news release: that the problem is serious.

Once the release authors decided to go beyond IARC’s focus on the “How sure are you?” question to address the size of the risk, they should have felt an obligation to make the size of the processed meat risk as clear as they could. At a minimum, they should have explicitly warned readers that even though processed meats are a human carcinogen, eating an occasional hotdog or sausage is not a huge cancer threat. To really put the size of the processed meat cancer risk into context, the release authors could have bracketed it, comparing it both to bigger cancer risks (like smoking) and to smaller ones (including many food ingredients and industrial chemicals that provoke widespread controversy).

And for further context still, the release could have looked at the bigger risk picture, not just the cancer risk picture. Cancer is far from being the main health risk from eating meats (including processed meats). Think about saturated fat and cholesterol, about heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, and obesity – all significantly bigger threats to health and longevity than colorectal cancer. And too much meat-eating is far from being the main dietary health risk. The biggies are too few calories (yes, starvation); too many calories (obesity again); and too little consumption of the nutrients in fruits, nuts, seeds, and vegetables.

Or IARC could have decided not to open the comparative risk can of worms at all. It wouldn’t have been hard to draw an explicit distinction between “How bad is it?” and “How sure are you?” and to stress that IARC isn’t saying that processed meats are especially bad or not especially bad, only that it’s pretty damn sure they’re at least a little bad.

Elsewhere, in fact, IARC explains that distinction clearly and repeatedly – but generically rather than with respect to processed meats in particular, and not in the news release itself.

At the bottom of the release, reporters are provided a link to a webpage entitled “IARC Monographs Questions and Answers.” ![]() Those who followed the link and read the four-page Q&A would have found the following on p. 3:

Those who followed the link and read the four-page Q&A would have found the following on p. 3:

What does the classification mean in terms of risk?

The classification indicates the strength of the evidence that a substance or agent causes cancer. The Monographs Programme seeks to identify cancer hazards, meaning the potential for the exposure to cause cancer. However, it does not indicate the level of risk associated with exposure. The cancer risk associated with substances or agents assigned the same classification may be very different, depending on factors such as the type and extent of exposure and the strength of the effect of the agent.

And this:

What is the difference between risk and hazard?

The IARC Monographs Programme evaluates cancer hazards but not the risks associated with exposure.

The distinction between hazard and risk is important. An agent is considered a cancer hazard if it is capable of causing cancer under some circumstances. Risk measures the probability that cancer will occur, taking into account the level of exposure to the agent. The Monographs Programme may identify cancer hazards even when risks are very low with known patterns of use or exposure. Recognition of such carcinogenic hazards is important because new uses or unforeseen exposures could lead to risks that are much higher than those currently seen.

And on page 4, this:

Why should two substances or agents classified in the same Group not be compared?

The classifications reflect the strength of the scientific evidence as to whether an agent causes cancer in humans but do not reflect how strong the effect is on the risk of developing cancer. The types of exposures, the extent of risk, the people who may be at risk, and the cancer types linked with the agent can be very different across agents. Therefore, comparisons within a category can be misleading. First, exposures may vary widely. For example, there is widespread exposure to the Group 1 agent air pollution, whereas far fewer people would be exposed to certain Group 1 chemicals, such as 1,2-dichloropropane. Second, the magnitude of risk associated with exposure to two agents may be very different. Active smoking carries a much higher risk of lung cancer than does air pollution, although both are categorized in Group 1. Third, the number of resulting cancers can be different; for example, tobacco smoking causes some common cancers, whereas 1,2-dichloropropane causes a rare bile duct cancer. This also applies to Group 2 agents. For example, radiofrequency electromagnetic fields and the prescription drug digoxin are each classified in Group 2B.

In other words, because the Groups indicate the strength of the evidence regarding a cancer hazard and not the risk, the risk associated with two agents classified in the same Group may be very different.

The release also has a link to a second Q&A ![]() , this one explicitly about the processed meat and red meat monograph. That five-page Q&A includes this on p. 2:

, this one explicitly about the processed meat and red meat monograph. That five-page Q&A includes this on p. 2:

Q. Processed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1). Tobacco smoking and asbestos are also both classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1). Does it mean that consumption of processed meat is as carcinogenic as tobacco smoking and asbestos?

A. No, processed meat has been classified in the same category as causes of cancer such as tobacco smoking and asbestos (IARC Group 1, carcinogenic to humans), but this does NOT mean that they are all equally dangerous. The IARC classifications describe the strength of the scientific evidence about an agent being a cause of cancer, rather than assessing the level of risk.

Four separate times in two different Q&As, IARC stresses the same point. Some readers may consider the links to these Q&As at the bottom of the news release convincing evidence that IARC is trying hard to prevent journalists and the public from inferring anything about the “How bad is it?” question from its claims about the “How sure are you?” question. Others may agree with me that IARC is trying to have it both ways: implying one thing in the news release that’s going to get a lot of use, while explicitly explaining that the implication is false on a webpage that’s going to get much less use.

It’s also worth noting that the meat-specific Q&A dives deeply – and I think fairly – into the “How bad is it?” question, precisely the question IARC keeps explaining is irrelevant to its classification scheme. In fact, more than half of this Q&A is about the size of the risk. On pp. 2–3, for example:

Q. How many cancer cases every year can be attributed to consumption of processed meat and red meat?

A. According to the most recent estimates by the Global Burden of Disease Project, an independent academic research organization, about 34 000 cancer deaths per year worldwide are attributable to diets high in processed meat.

Eating red meat has not yet been established as a cause of cancer. However, if the reported associations were proven to be causal, the Global Burden of Disease Project has estimated that diets high in red meat could be responsible for 50 000 cancer deaths per year worldwide.

These numbers contrast with about 1 million cancer deaths per year globally due to tobacco smoking, 600 000 per year due to alcohol consumption, and more than 200 000 per year due to air pollution.

Some reporters found their way to this instructive risk comparison and put it in their stories – though often at or near the bottom. Some reporters missed it but found their own similar risk comparisons elsewhere. And some reporters used no risk comparisons in their stories. Obviously, this information would have gotten better play if IARC had featured it in the news release instead of burying it in the Q&A. I assume that’s why IARC buried it in the Q&A.

In contrast to the news release (and the meat-specific Q&A), the Lancet article ![]() sticks to its mission: assessing the evidence that red meats and processed meats are human carcinogens. Here is the key passage regarding processed meats (with footnotes removed):

sticks to its mission: assessing the evidence that red meats and processed meats are human carcinogens. Here is the key passage regarding processed meats (with footnotes removed):

Positive associations of colorectal cancer with consumption of processed meat were reported in 12 of the 18 cohort studies that provided relevant data, including studies in Europe, Japan, and the USA. Supporting evidence came from six of nine informative case-control studies. A meta-analysis of colorectal cancer in ten cohort studies reported a statistically significant dose – response relationship, with … an 18% increase (95% CI 1·10 – 1·28) per 50 g per day of processed meat.

Data were also available for more than 15 other types of cancer. Positive associations were seen in cohort studies and population-based case-control studies … between consumption of processed meat and cancer of the stomach.

On the basis of the large amount of data and the consistent associations of colorectal cancer with consumption of processed meat across studies in different populations, which make chance, bias, and confounding unlikely as explanations, a majority of the Working Group concluded that there is sufficient evidence in human beings for the carcinogenicity of the consumption of processed meat.

The rest of the article supplements the crucial epidemiological evidence with supporting evidence from animal studies and mechanistic studies (studies showing how processed food might affect cells and genes in ways that could cause cancer).

The Lancet article uses the same factoid the release used: 50 grams of processed meat increases colorectal cancer risk by 18%. But it uses that factoid for a different purpose. The article focuses on the statistical significance of the effect, not its size. That’s what the “95% CI” (confidence interval) numbers show: that an effect this size had less than one chance in 20 of occurring by chance, so it probably wasn’t chance but rather a genuine, though rather small, effect of eating processed meats.

Since the article stays focused on the “How sure are you?” question, not the “How bad is it?” question, I don’t think its authors are obligated to point out that the statistically significant effect they cite is fairly small. And of course readers of The Lancet know how to interpret information about relative risk and statistical significance; they can see that the effect is fairly small but adequately proven. The release, on the other hand, seems to be using the “50 grams = 18% factoid” to suggest that the effect is big. And the release is aimed at an audience that’s unlikely to know better.

The coverage: Some got it wrong, most got it right

It’s helpful to distinguish short news stories about the IARC announcement from the longer ones. The former were typically written directly from the news release by general assignment reporters. The latter were the work of science and medicine reporters and incorporated information from other sources.

Consider first an emblematic short story from the “Learning English” simplified-language news service of Voice of America. The story is headlined, “WHO: Bacon, Hot Dogs Can Cause Cancer.” And the lede reads: “Eating processed meat can cause cancer, World Health Organization experts said Monday.”

This actually understates the level of confidence denoted by IARC’s Group 1. “Causes cancer” would have captured IARC’s answer to the “How sure are you?” question more accurately than “can cause cancer.”

But here’s what the story says about the “How bad is it?” question:

Dr. Kurt Straif is with the IARC. He said in a statement that the risk of cancer increases with the amount of meat a person eats. A person who consumes 50 grams of processed meat per day – about two pieces of bacon – increases his or her risk of bowel cancer by 18 percent….

Meat industry groups are protesting the WHO study. They say that meat is part of a balanced diet. They also say the causes of cancer are broad, and include environmental and lifestyle factors.

The WHO report cited the Global Burden of Disease project, which estimates that diets high in processed meat lead to 34,000 cancer deaths per year worldwide.

The VOA story truncates the Straif quote, leaving out Straif’s point that the individual risk is small. The story cites meat industry sources only on the obvious truths that meat is part of a balanced diet and that cancer has many causes – not on the size of the processed meat cancer risk. Most compellingly, the story includes a crucial “How bad is it?” number: 34,000 annual cancer deaths attributable to processed meats. The number comes from IARC’s meat-specific Q&A. But the story doesn’t include the equally crucial comparison data the Q&A provided, showing that processed meats are a much smaller cause of worldwide cancer than tobacco, alcohol, or air pollution.

My takeaway from this story and many others is that the reporter apparently got the impression from the release that the cancer risk of processed meats is a big problem. That impression influenced which parts of the release she included in her story. Even when she went to the meat-specific Q&A – which did a far better job than the release of putting the size of the risk into context – she went in search of information to bolster her story … and skipped right past the information that might have suggested her story was misleading.

I found a fair number of stories that, like this VOA story, passed along the impression that the cancer risk of processed meats is a big problem. The longer stories, especially the ones written by science and medical reporters, usually put the size of the problem into context.

But not always. NBC’s health reporter Maggie Fox wrote quite a long story that made it clear the IARC news isn’t exactly news – but never made it clear that the risk of processed meats isn’t exactly big.

Fox’s lede ignores the size of the risk and focuses on the increased certainty that processed meats cause cancer:

Processed meat, such as bacon or hot dogs, causes cancer, a World Health Organization group said in a long-awaited determination on Monday. The group said red meat, including beef, pork and lamb, probably causes cancer, too.

Many studies show the links, both in populations of people and in tests that show how eating these foods can cause cancer, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) said in its report, released in the Lancet medical journal.

“These findings further support current public health recommendations to limit intake of meat,” Dr. Christopher Wild, who directs IARC, said in a statement.

Most reports on the links between meat and cancer have been softened with some element of doubt, but the IARC uses clear and direct language in saying processed meat causes cancer. There are no phrases such as “may cause” in the report.

In the absence of anything in these first four paragraphs about the “How bad is it?” question, I’m guessing most readers and viewers would assume the risk is pretty substantial.

In fact, Fox’s 25-paragraph story says nothing that’s even vaguely relevant to the “How bad is it?” question until the 18th paragraph – and then the story uses only facts and numbers that make the risk sound very bad indeed. Here are the article’s last eight paragraphs:

“The experts concluded that each 50 gram portion of processed meat eaten daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18 percent,” the IARC said.

“For an individual, the risk of developing colorectal cancer because of their consumption of processed meat remains small, but this risk increases with the amount of meat consumed,” said IARC’s Dr. Kurt Straif.

“In view of the large number of people who consume processed meat, the global impact on cancer incidence is of public health importance.” The U.S. National Cancer Institute says several more studies are ongoing to assess the risk. The American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR), which studies the role of lifestyle and cancer, said the report fits in with its own advice.

“For years AICR has been recommending that individuals reduce the amount of beef, pork, lamb and other red meats in their diets and avoid processed meats like bacon, sausage and hot dogs,” AICR’s Susan Higginbotham, a registered dietician, said in a statement.

“AICR’s take-home message: by eating a healthy diet, staying a healthy weight and being active, AICR estimates that half of colorectal cancers could be prevented,” the group added.

“In fact, for the most common U.S. cancers, healthy changes to Americans’ diet, activity habits and weight could prevent an estimated one-third of cancers, about 340,000 cases a year.”

Cancer is the No. 2 killer in the United States, after heart disease.

Instead of comparing 34,000 annual processed meat cancer deaths with a million annual smoking cancer risks, Fox eschews both numbers. She combines all estimated cancer cases (cases, not deaths) that could be prevented if Americans ate right and exercised, allowing her to end her story with a compellingly high number – 340,000 cases a year – that has precious little to do with processed meats.

In fairness, Fox also wrote a sidebar entitled “Do I Have to Stop Eating Meat? Key Questions About WHO Group Report.” It’s only marginally better – for example, it uses IARC’s “a 50 gram portion of processed meat eaten every day raises the risk of colon cancer by 18 percent” without any context to help readers assess the importance of an 18% increase in relative risk. But the sidebar does include this valuable passage:

Is meat really as bad as smoking?

The American Institute for Cancer Research answers this one: “Although WHO now classifies both processed meat and cigarettes in the highest category of carcinogen, these classifications reflect the strength of the evidence behind them, not the level of risk,” the group, which researches links between diet and cancer, says.

“We hope that media coverage of this new report is careful to consider the appropriate real-world context: In some studies, participants who eat diets high in processed meat experience a risk for colorectal cancer that is nearly double that of non-meat-eaters. But according to the CDC, smoking cigarettes multiplies a person's risk for cancer by as much as 20 times.”

And the IARC itself says: “Processed meat has been classified in the same category as causes of cancer such as tobacco smoking and asbestos but this does NOT mean that they are all equally dangerous.”

Like IARC itself, NBC’s Fox buried the most important contextual information in a Q&A. Her main story replicates the “this is bad” impression of the IARC news release.

The Associated Press did much better. Here are the first two paragraphs of the unbylined AP story:

Paris — Hot dogs, bacon, cold cuts and other processed meats raise the risk of colon, stomach and other cancers, and red meat probably contributes to the disease, too, the World Health Organization said Monday, throwing its considerable authority behind what many doctors have been warning for years.

WHO’s cancer agency analyzed decades of research on the subject and issued its most definitive statement yet, putting processed meats in the same danger category as smoking or asbestos. That doesn’t mean, though, that salami is as bad as cigarettes.

Later the story adds helpful detail. It uses the risk comparison from the Q&A: 34,000 annual cancer deaths from processed meats versus 1 million from smoking, 600,000 from alcohol, and 200,000 from air pollution. It uses the Straif quote from the release, asserting that the individual risk from eating processed meats is small but the global impact is important. It also uses the relative risk claim from the release (50 grams a day of processed meat raises lifetime colorectal cancer risk by about 18%) without explaining what that 18% increase in relative risk means in terms of absolute risk – but it adds a quote from an independent expert pointing out that the effect of processed meat on colorectal cancer risk is a lot smaller than the effect of cigarettes on lung cancer risk.

But just the first two paragraphs get the gist of the story exactly right: The WHO experts are now throwing their weight definitively behind doctors’ longstanding warnings that processed meats give you cancer – though the risk is a lot smaller than the risk of smoking.

One more good example – the Guardian….

Here there were further notes on other examples I wanted to discuss – and then science writers’ dialogue with each other about how misleading/misunderstood IARC was, the meat industry’s response, “clarifying” tweets from Gregory Hartl of WHO, a follow-up WHO Q&A, etc.

This is the exact opposite of the usual “How bad is it?” versus “How sure are you?” confusion. The usual confusion – at least the one I usually complain about – is that warnings about high-magnitude risks so often sound as if the experts issuing the warnings were surer than they actually are.

At the height of bird flu anxiety in 2007, for example, I wrote a column entitled “A severe pandemic is not overdue – it’s not when but if.” Pandemic preparedness enthusiasts were making a big mistake, I wrote, when they implied that a disastrous pandemic was expected imminently. They were setting themselves up for people to feel misled – and skeptical about future pandemic warnings – if the bird flu pandemic didn’t materialize on schedule or if it didn’t turn out disastrous. So far, eight years later and counting, the bird flu pandemic hasn’t materialized. And the flu pandemic that did finally materialize in 2009, swine flu, turned out less deadly than many ordinary flu seasons.

The problem of sounding too sure about a possible disaster is generic. Here’s how I put it in a 2012 Guestbook entry on “Warning fatigue: when bushfire warnings backfire”:

The warnings that are most prone to warning fatigue are those that aren’t just warnings; they’re predictions. I’d love to see a test of the difference in impact of the two warnings described below – the difference in how much preparedness they inspire, and also the difference in how much warning fatigue they arouse if the warning turns out to be unnecessary or premature:

- “We can’t tell if X will happen or not, but it’s certainly possible, and it’s potentially so dire that we need to take precautions now even though they may turn out unnecessary.”

- “X is going to happen and is potentially dire, so we need to take precautions now.”

The difference between these two warnings is important. Option (a) dwells on the magnitude of the risk but doesn’t overstate its probability. It inspires preparedness without arousing warning fatigue. Option (b), on the other hand, overstates risk probability; it’s a prediction as well as a warning. It’s not only more vulnerable than (a) to warning fatigue; it’s also less credible and therefore less effective, even in the short term.

Thus an insurance salesperson who reminds you how awful it would be if your house burned down is likely to get more renewals than one who keeps insisting your house will probably burn down. A vaccination proponent who focuses on how sick the disease might make you is likelier to get you to roll up your sleeve than one who says you’ll probably get sick if you don’t get vaccinated.

Many warnings about uncertain but horrific risks have mistakenly opted for (b) when they should have picked (a). I’m thinking of George Bush proclaiming that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction … and also of environmentalists proclaiming that greenhouse gas emissions were having devastating effects on world climate. Bush turned out wrong while it looks like the environmentalists are turning out right – but that’s not the point. Both sounded far too confident far too soon.

If overconfident warnings are a common problem, overconfident reassurances are more common still. This is a recurring problem in public health communication – when Ebola briefly reached the U.S. in 2014, for example, and Director Tom Frieden of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention overconfidently told Americans that any U.S. hospital could cope with an Ebola case using its ordinary infection control procedures. And of course overconfident reassurance is a staple of corporate risk communication. I have spent decades urging corporate clients to stop insisting that there’s nothing to worry about. It’s hard enough to convince upset people that a risk is low if you’re respectful of their concern and the possibility that you could be mistaken; implying that you couldn’t be mistaken and their concern is idiotic is pretty much guaranteed to backfire.

In short, I’m used to organizations misrepresenting “How sure are you?” by conflating it with their actual answer to “How bad is it?” – whether their answer is “really bad” or “not so bad.”

IARC poses the opposite and less familiar problem. It misrepresents “How bad is it?” by conflating it with “How sure are you?”

Bear in mind that the “How sure are you?” question is usually of interest only if somebody is answering the “How bad is it?” question with a “pretty damn bad” answer. Imagine a pamphlet or presentation that began, “Today we’re going to talk about a small risk, too small to merit precautionary action. We want to share with you all the science that proves almost beyond doubt that this small risk exists.” Ho-hum. If you’re telling me the risk is big and I ought to do something about it, then I want to know how sure you are – also if somebody else is telling me the risk is big and you’re telling me it’s small.

IARC is really sure that processed meats pose a non-zero cancer risk to humans. It said so in a way that made “really sure” sound like “really bad.”

Why make a big deal out of your confidence that a problem exists if you’re not trying to say it’s a big enough problem to deserve precautionary action? The answer for IARC is that that’s their mission: figuring out what’s a human carcinogen (big or small) for sure and what’s only probably or possibly a human carcinogen. But everybody else is prioritizing problems, including cancer risks. And unless somebody says processed meats are a high-priority problem, who cares that IARC is surer than it used to be that they’re not a non-problem?

I think that’s at least a piece of why so many reporters thought IARC was saying that processed meats are a big problem. Reporters couldn’t imagine why IARC would be reaching out to them unless it thought processed meats were a big problem.

In fairness, “How bad is it?” and “How sure are you?” aren’t completely uncorrelated. All things being equal, the bigger an effect is the easier it is to find. So there’s likely to be better evidence showing a strong carcinogen is carcinogenic than showing a weak carcinogen is carcinogenic. But all things aren’t always equal. Sometimes a small effect is easy to prove because it has only one cause, for example; and sometimes a big effect is hard to prove because there’s so much noise in the data from other causes of the same effect. Sometimes you have debatable evidence about a big problem and incontrovertible evidence about a small problem.

This is like the distinction in statistics between the p value of some finding and various measures of effect size. Statistical significance or p tells you the probability that the effect you found could have occurred by chance; a low p means the effect was probably real, not random variation looking real. But statistical significance isn’t societal significance. A big, elegant study can get you a low p for a real but small and unimportant effect. A smaller or methodologically weaker study might achieve a less impressive p, leaving you in doubt whether the effect is real even though it might actually be a much bigger and more important effect.

I have cut some notes to myself on the article’s conclusion, and other points I might add. I’m leaving in, below, some notes to myself about IARC’s possible motives and the possible effects of the story.

12. Not crazy that they’d do it on purpose. The clearly explained quality-of-evidence story is hardly a story at all. Decent coverage pretty much required the misunderstanding. That way, they get it in front of millions of people – some for the first time, most as a reminder – that processed meat is bad for you. (And probably red meat too.) I’m guessing there was probably an impact. I’m pretty sure they’re guessing there was probably an impact. Maybe short-term: People who cut back for a little while. Maybe long-term: people reminded to cut back and get used to it. Incremental, mostly, not a paradigm shift for people. But surely a bigger effect than if they’d understood it was just about the quality of the evidence. Or if journalists had understood that and it was a small story.

13. I’m not sure what effect the good stories might have had – the ones that did what IARC didn’t do to clarify what it did and didn’t find. Lots of stories did the appropriate comparative risk analysis. Did the audience for those stories lose track of the distinction (immediately or soon) and learn the same bad-for-you message? Did they perhaps learn the opposite message: Not all that bad for you, compared to X or Y? I don’t know. I’m guessing the former.

13.1 In any case, the controversy made it a bigger story. Instead of a small story about improved data you got, at worst, a bigger story about how it may sound like it means worse for you but it’s really only improved data. More people saw or heard “processed meat” and “cancer” in the same sentence more times. How many people saw pictures of bacon and sausage with a skull-and-crossbones or an X drawn through it or whatever…. That’s probably the main thing. So even the irritated “IARC does crummy risk communication” stories helped rub in the lesson that processed meats are bad for you.

14. I’m assuming IARC did it on purpose, and not for the first time. It sees every ratchet up in evidentiary assessment as an opportunity to give the impression that X is more dangerous than we used to think, and even more fundamentally to get the dangerousness-of-X back in front of the public. (Regulators presumably know how to interpret IARC.) So they’re not lying. They’re not even cherry-picking their words to give a misimpression. They’re not briefing the case by cherry-picking facts and leaving other facts out. All they’re doing is talking about quality of evidence without explicitly saying that’s not the same thing as risk – and then talking about risk in a halfhearted way, focusing more on relative risk than on absolute risk. I can’t call it dishonest. But I do think it’s intentionally leaving people with the accurate impression that processed meats are carcinogens and therefore bad for you … and with an inaccurate impression that the experts just found out they’re more carcinogenic, more dangerous, than previously thought.

14.1. It’s not the worst example I’ve ever seen of intentionally misleading public health communication. That would probably be e-cigs: Convincing people (and regulators!) that e-cigs are as dangerous as cigarettes, encouraging regulatory and parental action that treats them similarly, and thus disincentivizing smokers from switching to vaping. That kills people, I think – all because public health professionals are so outraged at everything tobacco related; they feel burned by filters and lights and refuse to be burned again; either their hazard perception is distorted by their outrage or they’re just so angry they’d rather fight than encourage smokers to switch.

14.15 In contrast to e-cigs, in this case they’re “misleading” people about what IARC actually found – without saying anything false about it – in order to reinforce people’s accurate impression that processed meat is bad for you. Is that acceptable precaution advocacy?

14.2 The comparisons to cigarettes in some headlines were surely misleading: same category doesn’t mean just as important to avoid. The debunking stories and industry releases used equally accurate but misleading comparisons to sunlight and other benign or unavoidable or beneficial known carcinogens: same category doesn’t mean just as worth shrugging off and enjoying anyway.

15. The effect on reputation is supposed to be what keeps an agency from doing this sort of thing. And to be sure, nasty things were said about IARC…. BUT (a) IARC is almost invisible in between news pegs, so its public reputation doesn’t matter much, even to it. (b) WHO’s reputation maybe matters more, but still not much. (Though WHO’s reputation, battered by Ebola and swine flu, didn’t need another, albeit smaller hit.) (c) The government officials and experts aren’t fooled, and aren’t bothered; they know what’s true and they also mostly don’t disapprove of rubbing in the underlying truth with a misimpression about the news. They’re not about to outlaw processed meats, but appreciate IARC discouraging their consumption. (d) The forgetting curve for source is MUCH steeper than the forgetting curve for information; also the forgetting curve for rejoinders – people will remember mostly that scientists proved processed meat gives you cancer. (e) In general, the criticism of IARC was insiders talking to each other – science writers talking about IARC risk communication. The general public got mostly the story that processed meat is bad for you or at worst the more sophisticated story that, yes, it’s bad for you but not as bad as you may think they’re saying, they’re just saying the evidence got better.

Copyright © 2016 by Peter M. Sandman