Jody Lanard and I have been fielding inquiries from reporters covering various aspects of COVID-19. We decide which ones to respond to based mostly on whether the questions they ask provoke us to want to respond. Mostly we respond with emails rather than telephone interviews.

As events overtake their stories – events more relevant to the general public than the musings of a couple of newly unretired risk communication experts – most of the reporters end up using little or nothing of what we send them.

Here in chronological order are four of our recent emails:

- “Allaying Panic Is Not a Key Goal of COVID-19 Risk Communication Right Now” (to Ed Cara of Gizmodo, February 25)

- “How Should Anxious Doctors Talk to Anxious Patients about COVID-19; The Risk of Overreacting” (to Kate Johnson of Medscape Medical News, February 25)

- “Comparing COVID-19 to Seasonal Flu; Transitioning from Containment to Mitigation; the Powers of Local Public Health Officials” (to Nicoletta Lanese of Live Science, February 26)

- “Determination, Not Cheerleading: A Reaction to President Trump’s February 26 COVID-19 News Conference” (to Sarah Owermohle of POLITICO, February 27)

Allaying Panic Is Not a Key Goal of COVID-19 Risk Communication Right Now

Ed Cara used a little of this at the bottom of his February 27 overview of the crisis.

Every time a reporter mentions “panic” to me, I ask the reporter to consider his or her immediate surroundings. Is anybody in your family panicking about COVID-19? Any of your colleagues? Friends? People you see on the street? And then I want to know, “What do you mean by panic? Tell me an anecdote about a time when you or someone you know panicked.”

If we dumb down “panic” so it means something like alarmed interest, then the answer is probably yes, you do know people who are panicking about COVID-19. But if we stick to the original meaning of “panic” – doing dangerously harmful or self-defeating things that you would not do except that you are so upset that you can’t think straight – then I suspect the answer is no.

Thus:

- It’s not panicky to run uphill when a tsunami warning has been issued – it’s precautionary.

- It’s not panicky to stand in a long line in hopes of buying a package or two of facemasks – again, it’s precautionary.

- It’s not even panicky to decide to go out for burritos instead of Chinese food, out of a sense that people recently returned from China are likelier to be found in a Chinese restaurant than a Mexican restaurant – that, too, is precautionary, though empathy for the proprietor and workers might be a good enough reason to overcome this cautious impulse.

- And it’s certainly not panic to Google COVID-19, try to learn more about what might be coming your way, and start planning how to prepare.

One side effect of social media is how easy it is these days to find a genuine example of a panicked individual, doing something truly and obviously unwise because of out-of-control coronavirus terror. A reporter who wants to can find that one individual – for Ebola it was one woman sitting in an airport in a homemade hazmat outfit – and build a “people are panicking” story out that single online example. Bottom line: I don’t expect many people to be panicked by a CDC presser acknowledging that community transmission is inevitable in the U.S. sooner or later. I actually have the opposite fear. The acknowledgment you reference was awfully abstract.

Nancy Messonnier did extremely good risk communication in warning that community spread seems inevitable, but she wasn’t vivid or even explicit that “this means that probably soon we’re going to stop quarantining suspected cases or hospitalizing mild cases. And we’re certainly not going to recommend or tolerate locking down cities with outbreaks or even just clusters the way China and Italy have done, when we expect clusters are already incubating everywhere.”

Nor was Dr. Messonnier vivid or even explicit that social distancing and everyday disruption “could mean that your sister’s wedding might have to be canceled, and your company’s conference will almost certainly have to be canceled, as we transition from containment to mitigation, and social distancing becomes a crucial tool to slow the spread of the virus.”

She certainly wasn’t vivid or explicit about possible shortages – not just flowers for the wedding, but maybe more crucial goods like surgical masks and medications. It makes sense to want to avoid so-called “panic buying” (also more precautionary than panicky, in my judgment). But it also makes sense to help people understand the likely shortages to come and motivate them to start stocking up, ideally not too quickly.

But Jody and I have high praise for Dr. Messonnier for being explicitly clear that there is a great deal of uncertainty, and that CDC officials are bearing that uncertainty. She was emphatic that current recommendations and advice are “interim and fluid.” Most important, she warned people to expect changes in guidance as the experts learn more. This makes future changes less likely to be automatically perceived as mistakes, and thus less likely to reduce our confidence. (Of course actual mistakes should be candidly acknowledged as such, not attributed to new knowledge.)

My most fundamental response to your question: “Too scary” exists as a possible messaging problem. But I think most sources are too worried about sounding too scary, and not worried enough about sounding scary enough.

Everyone’s fear of scaring people has delayed the inevitable and necessary adjustment reaction – the Oh my God (OMG) moment when the public first realizes that the virus is spreading as we speak, that it will probably get here soon if it’s not here already, and that we’re probably facing a tough time in the months to come: tough in terms of widespread illness, some of it severe and even deadly; and tougher in terms of widespread disruption, from shortages of things we need to overcrowded hospitals to having to cancel conferences and weddings and even funerals. People have to get through their adjustment reaction before they can get down to the hard work of preparedness.

I have advised clients for decades to worry less about frightening people. In 2003, Jody Lanard and I wrote “Fear of Fear: The Role of Fear in Preparedness … and Why It Terrifies Officials” – which included a section on the most extreme version of official fear of fear: “panic panic.” When a devastating tsunami struck Southeast Asia in late 2004, officials and experts who knew it might be on its way decided not to warn the public. They were afraid a warning might lead to panic. See “Tsunami Risk Communication: Warnings and the Myth of Panic” for a discussion of this literally fatal error.

Most of the rest of this response is adapted from “Fear of Fear” – but feel free to quote it as coming from an email I sent you today.

There are three audiences to think about.

- When people are apathetic about some risk, it is very difficult to scare them. Every doctor knows how hard it is to pierce a patient’s apathy with alarming messages about smoking, obesity, or other risky lifestyle decisions. When you’re trying to arouse appropriate concern in an apathetic audience, there is near-zero likelihood that you will overshoot the mark and propel people into a panic attack. Excessive fear exists – fear so extreme it paralyzes instead of mobilizing. But people rarely catapult from apathy to panic because of something somebody said.

- When people are already upset about some risk, alarming messages tend to be paradoxically calming. Again, doctors know this already: Worried patients often experience even a dire diagnosis as the other shoe dropping at last – especially if the doctor finds the right balance between compassion and matter-of-factness. What really tends to devastate already frightened people is false reassurance, which leaves them alone with their fear and undermines their confidence in whoever is trying to reassure them.

- Only one group of people is at risk from warnings: those whose fear is so deep it has driven them into denial. Scary information can drive this group more deeply into denial. They need to be seduced gently out of their denial – but not with false reassurance; rather, with respectful validation of the fear they can’t bear to let themselves feel. You can do this without accusing people of a fear they’re unwilling to acknowledge. “Many people are understandably frightened” is better than “You must be frightened.” “Some of us are frightened” is better still. But even “you must be frightened” is better than “don’t be frightened.”

Respectful validation of fear is also key when you’re talking to someone who’s frightened and knows it. Fear is likeliest to escalate into terror or panic or to flip into denial when it is treated as shameful and wrong. “It’s natural to be afraid, I’m afraid too” is a much more empathic response to public fear than “there’s nothing to be afraid of.” If we want people to bear their fear, we must assure them that their fear is appropriate.

Even fear that is statistically inappropriate can be validated as understandable – and that validation is an important first step toward guiding people away from inappropriate fear. (This is even true of hurtful, stigmatizing fear – fear of contact with Chinese people and businesses, for example.) Leaders who are contemptuous of people’s fear have a much tougher time explaining the reasons why they needn’t be afraid.

To help people bear their fear if it’s appropriate, and to help people overcome their fear if it’s excessive or misplaced, first show empathy about their fearfulness.

Other approaches that help:

- Give people things to do – action binds anxiety.

- Give people things to decide – decision-making provides more individual control, which makes fear more tolerable.

- Encourage appropriate anger (at the virus, not the Chinese!) – the desire to get even often trumps feelings of helplessness.

- Encourage love, camaraderie, and volunteerism – soldiers, for example, fight for their friends and for their country; resilience is strongest when it’s communitarian.

- Provide candid leadership – we get more frightened when our leaders seem to be over-reassuring us.

- Show your own fear and show you can bear it – leaders who seem fearlessly unconcerned are little help to a fearful public.

How Should Anxious Doctors Talk to Anxious Patients about COVID-19;

The Risk of Overreacting

Kate Johnson’s February 25 article, “COVID-19: Time to ‘Take the Risk of Scaring People’” was based mostly on a February 22 piece Jody Lanard and I had written, “Past Time to Tell the Public: ‘It Will Probably Go Pandemic, and We Should All Prepare Now’.” Kate had emailed me some follow-up questions, but my answers didn’t get to her in time for her first story. She used some of them in a second story on February 27, “COVID-19 Preparedness: Clinicians Can Lead the Way.”

-

Overall, the sense I get from your piece (for our clinician audience) is: It’s time to stop being overly cautious in talking about this and risk scaring people. Could you elaborate?

(I have deleted my answer to this question, which was virtually identical to the last half of the email to Ed Cara just above.)

Has clinicians’ fear of scaring people been harmful to this point (outside of Asia) in terms of impeding the public’s emotional, intellectual and actual preparation?

I think everyone’s fear of scaring people has delayed the inevitable and necessary adjustment reaction – the OMG moment when the public first realizes that the virus is spreading as we speak, that it will probably get here soon if it’s not here already, and that we’re probably facing a tough time in the months to come: tough in terms of widespread illness, some of it severe and even deadly; and tougher in terms of widespread disruption, from shortages of things we need to overcrowded hospitals to having to cancel conferences and weddings and even funerals. People have to get through their adjustment reaction before they can get down to the hard work of preparedness.

Jody and I are hearing lots of stories of doctors pooh-poohing patients’ concerns about coronavirus, just as we documented clinicians’ disdain for patients who wanted just-in-case prescriptions for Tamiflu when a bird flu pandemic looked like it might be imminent.

I don’t especially blame clinicians for “impeding the public’s emotional, intellectual, and actual preparation.” But I do think clinicians can help lead the way. People trust their doctors a lot more than they trust government leaders, even public health leaders. Scary news sinks in a lot better when they hear it straight from a doctor they trust than when they hear it third-hand from a newscaster quoting a CDC official voicing pre-approved, watered-down talking points.

It’s also relevant that clinicians have good reason to be fearful for themselves and their staffs. People infected with COVID-19 and people who suspect they might be infected with COVID-19 will soon be crowding their doctors’ offices, and street clinics, and hospital emergency rooms. Masks may be in short supply – and may not be sufficient to do the job. Thousands of healthcare workers have been infected with COVID-19 in China. Several Japanese healthcare workers were infected aboard the Diamond Princess. And even clinicians who are inured to the risk of COVID-19 infection have reason to be worried about the months of overstressed overwork that loom before them.

Over the past couple of weeks, Jody and I have gone through our own OMG adjustment reactions as we realized that we’ve been Practicing for The Big One for decades and now it looks like this is it. We watch the infectious disease experts we know go through their OMG adjustment reactions as they confront the scary emerging realities of COVID-19. Clinicians who go through their own OMG adjustment reactions now will be more empathic and helpful when their patients go through theirs.

What has changed in the last day or so that I am hearing, for the first time, the OMG factor publicly from clinicians?

Probably the rapidly increasing community outbreaks in Italy, South Korea, and Iran, and the shocking lockdowns of cities in Italy. These developments make vivid the fact that pandemic spread is really happening, and that words like “stop” or “prevent” are no longer in play.

Technically speaking, this is how exponential growth works. It doesn’t look too bad until it looks very bad.

The disaster in China surely presaged a pandemic. WHO thinks that China’s draconian response significantly slowed the spread of the virus, both within China and outward to the rest of us. Travel bans presumably also helped slow the spread. But nearly all experts agreed that these measures couldn’t stop the spread, despite the cheerleader rhetoric of the WHO director general. Lockdowns and travel bans were useful only to buy time for preparedness efforts. I’m sure vaccine developers used the time. I hope hospitals did. Sadly, the vast majority of the general public did not, neither logistically nor emotionally.

I don’t have a sense of what most doctors were saying to their patients about COVID-19 during the past month, and I don’t know how what they’re saying has changed in the past few days. If as your question suggests they’re getting to and through their own adjustment reactions, that’s good. I’d rather praise them for getting through it now than criticize them for not getting through it sooner. Now they can help their patients get through it too.

Maybe chaos in China wasn’t a clear enough signal of what was coming. Maybe it took the increasingly obvious epidemic curves in South Korea, Japan, Italy, Iran…. Maybe it took some U.S. experts and officials getting clearer in their public statements that a pandemic is almost inevitable and that “pandemic” means here too, not just all those other places. I’m grateful and a little surprised that you think U.S. clinicians have made this crucial transition. Finally? Already? I’ll go with “already” – if you’re right, it didn’t take an explosion of U.S. cases or even a sizable U.S. cluster to launch the medical profession’s adjustment reaction. Kudos for that.

What do you say to those who suggest you're overreacting?

Here’s what Jody and I always say about accusations of overreacting.

In times of uncertainty, it’s impossible to titrate your level of expressed alarm perfectly. You have to guesstimate how bad things will get, knowing that you may turn out wrong … in fact, knowing that to one extent or another you will turn out wrong. And if you’re responsible for guiding others – as clinicians are responsible for guiding their patients – you can’t decline to communicate until you’re sure. Here are three rules of thumb for this difficult situation.

- Err on the alarming side. It’s not “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” It’s darned if you do and damned if you don’t. Warnings that turn out excessive if the risk fizzles are more forgivable than reassurances that turn out dangerous if the risk metastasizes. I tell my clients to guesstimate two scenarios – the worst case scenario that’s not vanishingly unlikely, and the likeliest scenario – and then give about equal attention to each (being clear about which is which).

- Proclaim uncertainty. Overconfident over-reassurance is the biggest sin in crisis communication, but overconfident alarmism is also a mistake. It’s not good enough to acknowledge sotto voce that you might be wrong. Say it loudly, incessantly. As WHO’s David Heymann said during the SARS crisis, “We are building our boat and sailing it at the same time.” Almost as good: CDC’s Nancy Messonnier saying that their advice is likely to be “interim and fluid” as knowledge evolves. Former acting CDC Director Richard Besser used the same words when he announced that “swine flu” was spreading in the U.S. in 2009.

- Don’t completely neglect the fizzle scenario. The credible best case scenario doesn’t deserve as much attention as the credible worst case and the likeliest case – but it’s your bulwark against accusations of overreacting. “You may be right. Here are a few ways this could fizzle…. If it does, I might feel a little foolish, but mostly I will feel hugely relieved. Meanwhile, as we hope and pray for the best, we should be preparing for the worst.”

Comparing COVID-19 to Seasonal Flu; Transitioning from Containment to Mitigation; the Powers of Local Public Health Officials

(No resulting story so far.)

Answers to your four questions are below.

COVID-19 has often been compared to the seasonal flu in news writing – do you feel these comparisons accurately convey the risks associated with the new disease?

We are risk communication experts, not infectious disease experts. But we doubt you’ll have any trouble finding infectious disease experts to explain some of the important ways COVID-19 is different from the average seasonal flu – starting with what looks like a significantly higher propensity to kill people.

A point that no self-respecting infectious disease expert ought to make is the one that all too many officials and experts have made over the past few weeks: that flu has killed many, many more Americans this season than COVID-19. That’s totally true, of course. But it is so obviously irrelevant that it immediately strikes many in the audience as a contemptuous barb, not as a helpful bit of context.

Unless it miraculously dies out, COVID-19 is in the early days of its likely path of devastation. Except for China, which is devastated already, nobody is worried chiefly about the damage COVID-19 has wrought so far. We are all worried about the damage it seems poised to wreak.

Public health professionals never mock people who angst over measles risk by noting how many more Americans die every year from flu than from measles. They never deride the public’s concern about the risk of vaping with a dismissive reference to flu. But when people are worried about something they’d rather we weren’t worried about, they all too often trot out the flu comparison.

By the way, Americans take flu more seriously than any other country on earth, if your measure is how many of us get our flu shots every year – despite knowing how woefully ineffective that particular vaccine is.

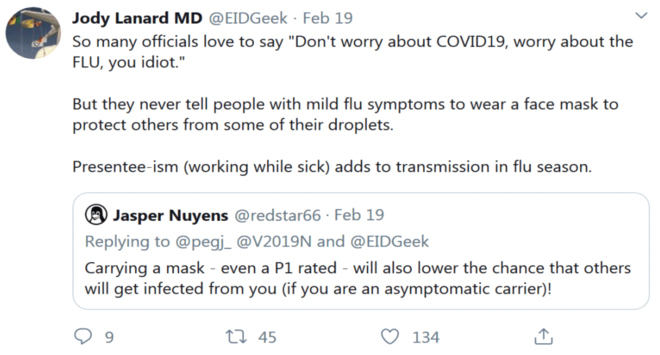

And as this recent tweet of Jody’s demonstrates, public health professionals somehow forget to worry about flu transmission when they’re focused on ridiculing people’s desire to protect themselves – and those around them – with facemasks.

From a risk communicator’s perspective, the key difference between COVID-19 and the seasonal flu is that COVID-19 is intrinsically much scarier. That has nothing to do with media sensationalism, by the way. In fact, decades of research going back at least to Three Mile Island in 1979 demonstrate that mainstream journalism gets much less sensationalist when reporters begin to feel the danger is real. (We can’t say the same for social media.) In our judgment, media are more to blame for overreassuring COVID-19 coverage than for sensational COVID-19 coverage.

So why is COVID-19 scarier than flu? People respond to risks in terms of what we term “outrage factors” or “fear factors” – factors that determine how upsetting a risk is independent of how dangerous it is. And COVID-19 has many of those factors that seasonal flu is lacking:

- COVID-19 is new, and new risks arouse more fear than familiar risks. People have already decided how worried to be about flu. They have decided what to do about it, and their decisions have morphed into habits that don’t require reconsideration. You don’t have to get upset all over again to get your flu shot; you just go get that annual flu shot chore out of the way. A new risk, on the other hand, requires new thought, new attention, and new emotional investment.

- COVID-19 is mysterious, with high levels of uncertainty. The experts (at least the honest ones) keep telling us how much they don’t know about this new threat. Worse, some of the experts are all over the media disagreeing with each other – and expert disagreement arouses even more anxiety than uncertainty. By contrast, flu is a known quantity. Experts do argue among themselves about some aspects of seasonal flu too, but they rarely do so on nationwide TV.

- COVID-19 raises issues of trust that seasonal flu doesn’t raise. The case numbers and other data coming out of China have been widely questioned. Japan’s mismanagement of the Diamond Princess is reminiscent of a 16th century Venetian Black Death quarantine – the ship was quarantined but its occupants were not – shattering confidence in a presumably highly competent health ministry. The downplaying of the largely unsuccessful rollout of U.S. coronavirus test kits has shocked many of us. Any trust issues about seasonal flu are comparatively minor, and almost always take place behind closed doors.

- Everybody knows that seasonal flu is a natural phenomenon. There’s no industry to blame, and no moral culpability to explore. COVID-19, on the other hand, is widely blamed on Chinese wet markets that continued to sell exotic animals for food, long after such markets launched SARS in 2003 – despite repeated warnings that such markets are known sources of novel infectious diseases, basically pandemics waiting to happen. Less credible claims also sow mistrust, including the claim that COVID-19 could be a biotech experiment gone wrong, or a biowar initiative gone right.

- We are all familiar with the range of flu seasons. Some years stress hospitals badly, cause lots of school and nursing home outbreaks, and lead to noticeable absenteeism (and unnoticeable presenteeism). Other seasons are mild. The signals that came out of China made COVID-19 look vastly worse than the flu. No flu season has ever shut down a huge and powerful country the way COVID-19 shut down China. The Wuhan situation did not look like “a bad flu season.” It looked like something unprecedented in our lifetimes. COVID-19 may or may not turn out catastrophic for our country and our world. The world hasn’t seen catastrophic influenza since 1918.

In the last week, in particular, news coverage has focused on whether the COVID-19 outbreak constitutes a pandemic yet. Rather than focusing on the terminology, what questions should journalists be asking? (That is, what does the public really need to know right now?)

As your question shows you know already, the debate over pandemic definitions is pointless. So is the quarrel over whether COVID-19 has or hasn’t reached pandemic proportions.

Many experts are using the term “pandemic” already. More will do so in the weeks ahead, and eventually the World Health Organization will give the pandemic designation its imprimatur.

Whether we think the virus is already spreading in enough places to be labeled pandemic matters less than whether we think it is probably spreading “here” or will be soon.

That’s the question that determines when it’s time to wind down traveler screening and quarantines and time to ramp up serious social distancing measures: canceling sports events, festivals, church services, wedding parties, and concerts; advocating for work-from-home policies; radically increasing hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette; and other anti-transmission practices.

In the U.S., we are nearing the end of containment and starting mitigation – what CDC’s Nancy Messonnier called a two-prong approach for now. But during the all-out containment period, very few officials told the public what the future mitigation practices would be like, if containment did not stop the spread. And even though they considered it a long shot, many officials gave the public the impression that containment would indeed stop the spread.

So we have a public ready to be shocked when their government stops quarantining people coming here from China, and stunned when they learn their long-planned weddings might have to be canceled.

Getting the public on board with this transition with practically no warning is a daunting risk communication challenge – arguably one of the key challenges right now in the U.S. An awful lot of people have been mis-taught that the increasingly futile containment measures would very likely protect them from COVID-19. WHO has exacerbated the problem by saying complimentary things about China’s draconian lockdowns and Italy and Iran’s somewhat less draconian ones. And U.S. officials have exacerbated the problem by saying complimentary things about our own travel bans and quarantines.

Now, somehow, they have to turn around and say, “We think containment efforts maybe helped slow the onslaught of COVID-19 in the U.S., but we know now that containment is not going to stop COVID-19 from spreading here. We’re starting mitigation, and will be winding down our unprecedented containment efforts, like quarantining travelers from China, which have become familiar to you.”

The core of the new message:

- that the virus might already be spreading “here” now, or soon will be;

- that our containment measures have done most of the good they could do to slow the spread; and

- that now our focus must switch from preventing it from getting here to managing the fact that it is here, or going to be here soon.

And then they need to explain the main implications of the new response phase.

This includes vividly talking about aspects of mitigation that are painful, sad, and alarming:

- The possible need to cancel many events including conventions, conferences, meetings, sports events, graduations, weddings, etc.

- The likelihood of massive healthcare system disruption if it turns out that this virus leads to very large numbers of severe cases in the same place over a short period of time.

- The prospect of significant disruption caused by high levels of absenteeism, interrupted supply chains, and other “secondary” effects that could do as much damage as the virus itself.

- And lastly, the potential for civil unrest, which nobody wants discuss at all.

As COVID-19 management strategies shift from containment to mitigation, it seems inevitable that many responsibilities (public education, healthcare, canceling mass events, etc.) will fall on local governments rather than federal. How can local officials best communicate disease risk to their constituents, particularly when national news tends to be “louder” and more generalized?

We haven’t thought much about this, so we don’t want to pontificate on it.

But pandemics typically roll around a lot. It seems likely that a COVID-19 pandemic will be like a flu season in this way – intense here and mild there this week, but maybe quite the opposite next week. Many social distancing strategies are deployed only during the times when the pace of local transmission is intense. So we’re guessing that there should be a very substantial role for local media, reporting on the pandemic management decisions of local officials. To paraphrase the late U.S. Senator Tip O’Neill: “All pandemics are local!”

Another point worth making: In the United States, public health policy is almost entirely a state responsibility. The CDC advises, supports, and funds; with rare exceptions, it does not compel. Within states, the division of authority among state, county, and city varies. But more often than not, local health officials have enormous power – in an emergency, their power often exceeds that of the political leaders whose policy choices they are accustomed to implementing.

Of course local health officials don’t often use their power; they’re usually more comfortable advising politicians than overruling them. But it might be worth remembering that they do indeed have power. In 1892 there was a cholera epidemic in New York City. The health commissioner, Cyrus Edson, famously said that he had the power to seize City Hall and turn it into a hospital if he wanted.

Finding out what power local health officials actually have today might be a good story for you.

Given that mitigation strategies also place heavy responsibility on individuals, in terms of their day-to-day behaviors, how can local leaders be empowered to deliver risk information and encourage adherence among those in their communities?

Same answer. As a rule, decision-making power in a public health emergency belongs more to local leaders than to national leaders, and more to public health officials than to politicians.

That leaves a lot of follow-up questions unanswered, of course.

- Can national leaders overrule local and state leaders if they choose to?

- Can politicians overrule public health officials if they choose to?

- Are we simply dead wrong about the locus of power in a public health emergency?

- Insofar as we’re right, how often will local leaders dare to challenge national ones, and how often will public health officials dare to challenge politicians?

- And above all, who’s likely to make the wisest decisions, and who’s likeliest to be able to lead the public through a difficult time?

Determination, Not Cheerleading: A Reaction to President Trump’s February 26 COVID-19 News Conference

Sarah Owermohle emailed Jody on February 26 for her story on reactions to the President’s news conference. This is our joint response. No story yet.

On Tuesday, CDC coronavirus lead Dr. Nancy Messonnier raised the alarm a notch about the prospects of coronavirus spreading in the U.S. She did this with Churchillian determination and great humanity.

On Wednesday she did not appear on the stage with President Trump.

There’s black humor about this going around in our little risk communication community: How is Dr. Nancy Messonnier’s coronavirus messaging like a village in Lombardy, Italy? Answer: They are both locked down.

Instead, we watched the President violate the very first guideline in our risk communication training manual: Don’t over-reassure.![]() And he did it over and over, more times in one speech or document than we have ever seen. We have an amazing collection of leaders saying, “The situation is under control,” and “There’s no reason to be alarmed,” in dozens of pre-crisis situations when the near future looked dire.

And he did it over and over, more times in one speech or document than we have ever seen. We have an amazing collection of leaders saying, “The situation is under control,” and “There’s no reason to be alarmed,” in dozens of pre-crisis situations when the near future looked dire.

Even in real time, even before the situation turns dire, this sort of over-reassurance sounds fishy.

Everyone knows the comparison to influenza sounds fishy. You don’t say in September that the risk of influenza is very low, you try to warn people that by December there will be an epidemic. You don’t wait until the hurricane is crossing the coast to tell everyone to brace themselves and hunker down. If it’s like the flu, what the hell happened in Wuhan?

Trump also violated the precepts of uncertainty communication. In our totally free training manual (![]() 5MB) – we’re retired now, except for this – we advise that officials acknowledge and even proclaim their uncertainty.

5MB) – we’re retired now, except for this – we advise that officials acknowledge and even proclaim their uncertainty. ![]()

When we trained leaders in risk communication, we exhorted them to acknowledge and even proclaim uncertainty in the face of a looming novel crisis. We used to say: sounding more certain than you are rings false, sets you up to turn out wrong, and provokes adversarial debate with those who disagree. Say what you know, but emphasize what you don’t know, and the possibility that some of what you “know” may turn out wrong as the crisis evolves. Show you can bear your uncertainty and still take action.

This is what Nancy Messonnier did in her press conference on Tuesday, warning us that the coronavirus spreading around the world was looking worse, and might well happen here too. She warned us to get ready for possible social disruption. It would help even more if people visualize in advance what this might mean before it happens, so they can cope better if it does happen: social distancing measures like canceled sports seasons, graduations, conventions, and weddings; transportation and infrastructure problems; all kinds of shortages; difficulty refilling prescriptions because of supply-chain disruptions.

This is what former CDC acting director Richard Besser did magnificently when it looked like the novel swine flu virus was likely to launch a pandemic. Thank goodness that pandemic turned out mild.

They were both treating the public like grownups.

But Trump treated us like children, telling us not to worry our pretty little heads, not to over-react to media hype and cause the stock market to crash. He didn’t urge us to brace ourselves for what might happen, and imagine what might happen, and prepare.

Which leader would you trust to guide you towards and through a potentially high-magnitude, obviously high-probability crisis like a coronavirus pandemic? The question answers itself.

If Nancy Messonnier’s bracing determination has been locked down in favor of President Trump’s cheerleading, all of us will be going into that possible miserable future way less prepared, logistically and emotionally, than we could have been.

Copyright © 2020 by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard