What to Say When a

Pandemic Looks Imminent:

Messaging for WHO

Phases Four and Five

by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard

(Page 1 of 4)

In October 2005, a North Dakota public information officer sent one of us (Peter) an email, noting that she had searched this website without finding “any suggested messages for the public at the start of and through the height of” an influenza pandemic. We had written about pre-pandemic messaging – what to say now about a possible future flu pandemic. But her department was about to do a tabletop drill for an actual pandemic. What messages did we recommend?

Over a year later, we finally found the nerve to work on the first part of her query: some messages for when it looks like a pandemic is about to start.

The list of 25 “pandemic imminent” messages contained in this long article is not intended to be comprehensive or definitive. Some of the more situation-specific messages (how the initial outbreaks arose, where to get more information, etc.) have been omitted. And some of what’s here may turn out not to be technically accurate.

Our main goal is to suggest, in considerable detail, the sorts of messages we think people will need to hear when a pandemic looks imminent – focusing especially on the ones that are counterintuitive, that government and corporate sources are likeliest to neglect. We have tried to explain the rationale for each message in terms of crisis communication theory.

Column Table of Contents

Imminent Pandemic Standby Messages

| 1. | It looks like a flu pandemic is about to start. |

| 2. | It’s no longer about the birds. |

| 3. | This is a new warning, more urgent than any warning so far. |

| 4. | The experts still aren’t sure. |

| 5. | We don’t know how bad it will be. |

| 6. | Here’s what we know so far about the severity issue. |

| 7. | It may be very bad. Society will survive, but it may be very bad. |

| 8. | We may have a window of opportunity now to make some practical preparations. We must make the most of it – even though the effort may be wasted if a severe pandemic doesn’t happen. |

| 9. | What matters most is how households, neighborhoods, community groups, and businesses prepare. |

| 10. | Individual and community preparations will focus on three tasks – reducing each person’s chance of getting sick, helping households with basic survival needs during a pandemic, and minimizing and coping with larger societal disruption. |

| 11. | Social distancing will be important but unpleasant. |

| 12. | School closings present a particularly difficult social distancing dilemma. |

| 13. | Hand-washing is far from a panacea. But it’s easy, it’s under your control, and it has no significant downside. |

| 14. | Like washing your hands, wearing a facemask may help a bit. But it has more downside than washing your hands. |

| 15. | Getting ready for a pandemic is largely about preparing for possible shortages. |

| 16. | It’s probably too late to stockpile much now, but do what you can. |

| 17. | Now is also the time to think about how you will care for loved ones at home. |

| 18. | To get ourselves through the hard times that may be coming, we will need volunteers. How can you help? |

| 19. | If the pandemic is severe, the hardest job won’t be coping with the disease itself. It will be sustaining the flow of essential goods and services, and maintaining civil order. |

| 20. | Here’s what the government will be doing.… |

| 21. | Try not to switch off. Try not to overreact. |

| 22. | Even though we hope riots, panics, and other sorts of civil disorder will not be common, it is important to be on guard. |

| 23. | We are going into this pandemic crisis determined to be candid. That means you need to expect bad news, confusing changes in policy, conflicting opinions, and conflicting information. |

| 24. | Listen to stories about what 1918 was like, and to guesses about what the coming pandemic may be like. |

| 25. | Here is some more information you may want to know.… Here is how you can get additional information… Here is how you can give us your feedback and suggestions.… |

We have looked at a lot of pre-pandemic messaging – messaging designed for use now, as opposed to when a pandemic looks imminent. Many international organizations, non-government organizations, national governments, state and local governments, and corporations are trying to tell their publics what might be coming someday. An organization just starting to work on pre-pandemic communications can borrow freely from this existing messaging. In the U.S., the Department of Health and Human Services brought in risk communication expert Vincent Covello to help recast its pre-pandemic messages into 74 pages of “message maps,” now posted on its website. Other sources of pre-pandemic information are using or adapting some of these messages.

Our own short list of pre-pandemic messages is contained in our December 2004 column, “Pandemic Influenza Risk Communication: The Teachable Moment.” More than two years later, it strikes us as too preoccupied with vaccines. (The flu vaccine shortfall of 2004 had provided that particular pre-pandemic teachable moment.) And it doesn’t empathically acknowledge and correct some misimpressions that have since become common. (Some version of “It’s not about the birds!” definitely needs to be a message.) But much of it still looks useful. Peter’s October 2005 column on “The Flu Pandemic Preparedness Snowball” has some additional suggestions for pre-pandemic messaging.

But we can find very few posted or published standby messages for use when a pandemic is about to start.

It’s possible that collections of standby messages have been developed and are being held until they’re needed. And some officials have told us they are working on pandemic messages, which they plan to publish soon. But when conference speakers present lists of their organizations’ pandemic preparedness activities, the lists rarely include “develop standby messages.”

In any case, standby messages are not readily available now. At the pandemic tabletop exercises we have attended, participants invariably develop their own messages on the spot. No one ever suggests using existing standby messages. If such message repositories exist, even in draft, it would be useful for their sources to post them (as HHS has done with its pre-pandemic messages), so others can comment on them and borrow from them.

We think this is a shocking gap. A novel influenza virus could launch a pandemic at any moment. The most worrisome animal flu virus right now, H5N1, has been around since 1997; it has been a focus of worldwide attention at least since late 2003. If H5N1 (or some other new flu virus) starts transmitting easily from human to human, a pandemic will be imminent. Nobody knows how quickly it will spread once that happens.

The moment that happens, pandemic risk communication will change radically. And as things stand right now, it looks like most pandemic risk communicators will be writing their messages nearly from scratch.

Not quite from scratch. Many organizations have developed guidance documents of risk communication principles and strategies. If they’re taken seriously, and operationalized effectively, these guidance documents can help a lot. See particularly the World Health Organization’s “WHO Outbreak Communication Guidelines” (2005) and the pandemic influenza risk communication training course developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Also worth examining are the communication objectives for each phase in the “WHO Global Influenza Preparedness Plan.” Among the national communication objectives listed for Pandemic Phase 5 are these two, which require just the sorts of difficult crisis communication approaches we try to exemplify in this column:

- Redefine key messages; set reasonable public expectations; emphasize need to comply with public health measures despite their possible limitations.

- Inform public about interventions that may be modified or implemented during a pandemic, e.g. prioritization of health-care services and supplies, travel restrictions, shortages of basic commodities, etc.

Guidance documents like these are a good start. But they fall far short of a list of standby messages to build on and then quickly deploy when a pandemic looks like it’s starting.

Most of this column will be our first crack at a list of standby messages, annotated in terms of risk communication principles.

As a rule, we like to pepper our columns with examples – good ones and bad ones. This overlong column will be an exception, because there aren’t many examples.

Coping with Riveted Attention

The crucial distinction between pre-pandemic messaging and pandemic messaging is obvious. There’s all the difference in the world between warning people about something that might happen (nobody knows when) and guiding people through something that looks like it’s about to happen or already happening.

The crucial distinction between pre-pandemic messaging and pandemic messaging is obvious. There’s all the difference in the world between warning people about something that might happen (nobody knows when) and guiding people through something that looks like it’s about to happen or already happening.

In terms of the four kinds of risk communication, pre-pandemic messaging is a kind of precaution advocacy. Hazard is potentially high but outrage is low, and as in traditional public relations, the main problem is grabbing and holding people’s attention. But once the experts have said a pandemic looks imminent, getting people’s attention won’t be much of a problem. The task will shift from precaution advocacy to crisis communication. Hazard and outrage will both be high, and the main problem will be coping with rightly anxious, riveted attention.

Here are some of the major crisis communication challenges when a pandemic looks imminent:

- Balancing competing needs to warn, reassure, guide, and inform.

- Keeping up with constantly evolving pandemic information, management decisions, and outcomes.

- Addressing the inevitable discrepancies among the messages and management decisions of various governments, and even within governments.

- Addressing the crisis of confidence that will accompany the early moments of an approaching pandemic, fueled by such predictable questions as these: Why weren’t we better prepared? What do you mean you have to ration medical care? How dare you say other people’s needs are higher-priority than mine?

- Helping people steel themselves to bear the emotional toll of what may (or may not) be a devastating personal, local, national, and worldwide catastrophe.

- Helping people choose wise rather than unwise pandemic precautions, and helping them implement their choices steadfastly, especially when all available precautions feel so inadequate.

- Just dealing with the crush of urgent media and public demands for answers, especially when there are no answers.

By contrast, the biggest pandemic risk communication problem right now – in mid-March 2007 – will disappear. That problem, of course, is regaining and holding the attention of the media and the public, for whom pandemic preparedness has already had several very brief moments in the sun and is now passé. Even those moments in the sun were distorted by the widespread misimpression that the pandemic risk goes up when bird flu in birds comes closer. In surveys, people continue to show a lot more awareness of “bird flu” than “pandemic flu.” The pandemic risk has managed to become passé without ever being properly understood.

Governments, businesses, and other institutions are paying increased but quiet attention. The media have mostly moved on for the moment. The public, for the most part, has yet to be properly engaged.

With attention as spotty as it is, inspiring preparedness is difficult. Correcting misimpressions – both the misimpression that pandemics are spread by birds and the misimpression that H5N1 somehow “went away” – is even harder.

There is still news coverage of far-away bird flu outbreaks and human bird flu deaths. And there is still some low-level coverage of local pandemic preparedness meetings. But as we write in mid-March 2007, you have to search to find media content on these topics.

Some of the coverage that remains, moreover, is hostile to preparedness: scoffing accusations of official fear-mongering. Endless end-of-the-year news roundups mentioned 2006 as the year the pandemic didn’t arrive. Commentators stressed that there were only 80 human bird flu deaths in 2006, with most of those in the first half of the year – as if that meant a pandemic was now unlikely. In February 2007, John Stossel of ABC News hosted a two-hour documentary on “Scared Stiff: Worry in America.” “Bird flu” came up in passing several times, as an example of a foolish fear too obvious to belabor. The distinction between bird flu and pandemic flu was never raised.

All this will change if a novel flu virus starts transmitting more and more efficiently among humans, leading official health agencies to announce that a pandemic is probably imminent. There will be more coverage than we know what to do with.

It will be mostly responsible coverage, too. A little-recognized truth about media sensationalism is that it almost disappears when a crisis is obviously serious. (See Peter’s September 2006 column on “Media Sensationalism and Risk.”) An emerging pandemic will be dramatic enough on its own. Reporters will cover it heavily, but they won’t have to spice it up.

Of course once a pandemic reaches here – wherever “here” is – it will dominate local coverage. There will be few if any unrelated stories of importance. Still, sensationalism will be rare in the mainstream media. To the contrary: If the pandemic is severe, overly reassuring coverage may be a problem, as it was in the 1918 pandemic.

If the next pandemic turns out mild, if the case fatality rate is low and societal effects are hard to see, the media will soon turn their attention elsewhere. The mop-up coverage will have to choose between two storylines: “This is more serious than it looks on the surface” or “What an anticlimax! How did the experts get it so wrong?” Bet on the latter.

But between the moment when it looks like a severe pandemic might be about to start and the moment when it looks like it didn’t happen, or it has turned out mild, or it’s over, pandemic communication will thrive. There will be a lot of attention.

Which is a good thing, because there will be a lot to say.

The suggested messages in this column are factually nonspecific, since nobody knows yet how the next pandemic will unfold. Specific information will become the focus of additional messages, not included here, such as: Where did the human cluster emerge first? Where has the disease spread to so far? What is being done to try to halt or slow its spread? What symptoms seem to be most common?

Instead of factual specifics, we are focusing mostly on thrust and tone, on what we often call “metamessaging” as opposed to messaging. Especially in a crisis, how you frame information is often as important as the actual facts. Yet communication planners seldom pay much attention to metamessaging issues. Readers who like the metamessaging that follows can use it as a model, even though the actual facts will be different. Readers who disagree with our metamessaging recommendations can start thinking more explicitly about what sort of metamessaging they plan to do instead.

The suggested messages in this column are also long-winded. That’s partly because everything we write together tends to be long-winded. But there’s a better reason. Right now the media and the public have a limited appetite for pandemic information; sources need to talk in sound bites. But by the time a pandemic is on its way, the appetite for pandemic information will be insatiable. Sources won’t always need to cut to the chase; they will need to fill the information vacuum.

Of course there will be a market for short, clear, bottom-line messages too. Some people won’t have the time or the language skills to absorb a lot of detailed information. Some will be too stressed. They’ll just want to be told what to do. But most people’s media consumption goes up in crisis situations. Think about 9/11, or the assassination of President Kennedy, or Pearl Harbor. We’ll have hours of riveted attention, not seconds of easily distracted attention. So we will need both simple cut-to-the-chase messages and longer, more complex messages.

Risk communication expert Vincent Covello has rightly pointed out that when people are anxious or upset their ability to absorb information deteriorates, so they can handle fewer messages and require simpler language. But there’s another force working in the opposite direction: When people are anxious or upset their motivation to absorb information increases. They really want to understand what’s going on and figure out how best to handle it.

If you doubt this, look at the information-seeking behavior of people newly diagnosed with a serious cancer. As Covello tells us, the emotional weight of the diagnosis makes it harder to learn. There are moments of denial when the patient simply cannot bear to learn; there are patients who never get past the denial. But a large number of cancer patients learn huge amounts of highly technical information about their condition.

In high-concern situations, it is important to stay focused on the questions people are asking and on the information you really need them to know, rather than going off into long, jargon-filled, hyper-technical explanations. And it’s important to keep your language simple and direct. But the content itself should not be oversimplified.

Some crises are so fast-moving you simply don’t have time to tell people everything they want to know. You have to get them evacuated or sheltered or medically treated instantly. But while ordering people around without much explanation is sometimes a necessity, it isn’t a virtue. When there’s time, most people would much rather know why they should do what you’re telling them to do. And if it’s important for them to exercise initiative, to take care of themselves and their neighbors, not just follow your orders, they really need to understand the reasoning behind your instructions.

After people understand the reasoning, they may find simplified summaries enormously valuable. Many emergency response professionals carry wallet cards to remind them of key steps to take in high-stress situations when memory sometimes falters. Mnemonic devices are similarly valuable. Fire training always includes the mantra: “stop, drop, and roll.” CPR training inculcates the ABCs: “airway, breathing, circulation.” These aren’t replacements for detail; they are reminders of well-learned basics.

We feel the same way about the crisis communication pocket cards distributed by the CDC and WHO, and about our own checklist  of 25 crisis communication recommendations. They are useful as reminders, not as primary instructions.

of 25 crisis communication recommendations. They are useful as reminders, not as primary instructions.

A pandemic is a slower-moving crisis than a fire or a patient who isn’t breathing – or a tsunami or a terrorist attack. Say it all. Say it understandably. Say it empathically. Repeat the crucial bottom-line points – the ones on your message maps, if you have message maps – more often than the supporting points. Organize the available information in layers so people don’t get lost. Just as a good technical report has an executive summary, a body, and a bunch of appendices, so too pandemic information should offer the public choices among levels of complexity.

But say it all.

Pandemic Messaging Phases

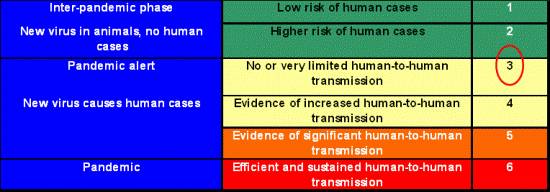

The World Health Organization distinguishes six pandemic phases. We are currently in Phase 3.

The World Health Organization distinguishes six pandemic phases. We are currently in Phase 3.

We’re no longer in Phase 1 because “a circulating animal influenza virus subtype [H5N1] poses a substantial risk of human disease.” We’re no longer in Phase 2 because there have actually been some “human infections with a new subtype”: H5N1 has successfully passed from a bird to a human almost three hundred times so far. There have also been a few cases of limited human-to-human transmission, but only among very close contacts. In WHO’s judgment this does not qualify as the “evidence of increased human-to-human transmission” required for Phase 4.

We’ve been in Phase 3 since 1997 (before the current phases were designated), when the highly pathogenic avian influenza strain H5N1 was identified in poultry and 18 humans in Hong Kong.

As the WHO chart shows, the distinctions among the WHO’s Phases 3, 4, 5, and 6 are qualitative, depending on whether human-to-human transmission is “very limited,” “increased,” “significant,” or “efficient and sustained.”

We want to propose a complementary but different set of phases for planning pandemic communications. The WHO pandemic phases are grounded solely in what the virus is doing. Our pandemic communication phases are grounded also in how “hot” the level of public concern is, and in where the disease is located.

| Communication Phase | WHO Pandemic Phase |

|---|

| 1. Pre-Pandemic Cold | 1 or 2 |

| 2. Pre-Pandemic Warm (little public attention) | 3 |

| 3. Pre-Pandemic Hot (teachable moment) | 3 or 4 |

| 4. Pandemic Imminent | 4 or |

| 5 |

| 5. Pandemic Elsewhere | 6 |

| 6. Pandemic Here | 6 |

| 7. Pandemic Elsewhere (again) | 6 |

| 8. Post-Pandemic | 1 or 2 or |

| 3 or even 4 (for a different strain) |

Communication Phase 1: Pre-Pandemic Cold

In WHO’s Phases 1 and 2, pandemic preparedness is off the public’s agenda, and most communication effort would be wasted. It still makes sense to lobby for improvements in public health infrastructure, vaccine technology, all-hazards preparedness, etc. But don’t expect to create a Communication Phase 1 pandemic buzz. Save your ammunition.

There may be occasional exceptions. Even though WHO is still in Phase 1 or 2, something may happen that suddenly propels you to Communication Phase 2 or 3. A seasonal flu outbreak may be especially severe, for example, or the seasonal flu vaccine supply may turn out contaminated and unusable. Or a severe respiratory disease of unknown origin may look like pandemic influenza for a while (as SARS did) before it turns out to be something different. The most important exception is right after a pandemic, when people may be willing to focus temporarily on improving preparedness for the next one. But if there’s no particular reason for people to be thinking about pandemics right now, the chances of inspiring much pandemic preparedness are next to nil.

Communication Phase 2: Pre-Pandemic Warm

In WHO’s Phase 3, where we are now, the opportunities to communicate improve. At least there’s H5N1 to point to. But people get used to looming threats on the horizon, and need something more to recapture their interest – a local outbreak in birds, for example, or the first human case someplace nearby, or a human-to-human cluster anywhere.

In between these teachable moments, it’s not easy to keep the general public (or the media) interested. Reaching out to stakeholders is more feasible. Thus Pandemic Communication Phase 2 is actually a pretty good time for companies to talk to their customers, suppliers, and even employees. They won’t get too strong a reaction – their problem will be apathy, not panic – but they can start building baseline awareness.

Communication Phase 2 is also a good time for all pandemic information sources to cement their progress with people whose awareness has already been aroused during prior teachable moments. Get them involved in company and community preparedness activities, urge them to share their concern with friends and coworkers, advise them on next steps in household preparedness, etc.

Communication Phase 3: Pre-Pandemic Hot

Communication Phase 3 is whenever the issue catches fire. That includes the periodic teachable moments we’ve already mentioned – a local bird outbreak, a nearby human case, a human-to-human cluster. It might also include less obvious teachable moments, such as a pandemic-focused movie or TV docudrama. The biggest day so far on the CDC’s pandemic website was the day pandemic expert Michael Osterholm appeared on “Oprah!”

A teachable moment of special importance occurs any time H5N1 (or any new animal flu strain) looks like it’s getting better at human-to-human transmission. That won’t necessarily mean that the World Health Organization is about to ratchet up to Phase 4. But it definitely means you should ratchet up to Communication Phase 3: Pre-Pandemic Hot. Any time there are rumors that WHO is even thinking about Phase 4, you’ve got a teachable moment. If and when WHO actually makes the move to Phase 4, you’ve got a gigantic teachable moment.

Capitalizing on teachable moments is crucial to the progress of preparedness. All too often, risk communicators get it backwards. When interest is low, they struggle unsuccessfully to persuade people to take the issue more seriously. Then something happens that forces people to take the issue more seriously, and suddenly the communicators pull back. Afraid of frightening the public, they fritter away their teachable moment with over-reassurances.

In country after country, we have watched as a local bird flu outbreak offered a chance to say, “Eating poultry is pretty safe, actually, but here’s what we’re really worried about….” In country after country, communicators focused on the first half of the message and ignored the second half. When bird flu rears its ugly head, pre-pandemic messaging, sadly, tends to disappear. (Ironically, the “chicken is safe” message is more credible if you are also giving people scary information about a possible future pandemic – which won’t be about the birds, once it begins.)

Bottom line: While you’re in Communication Phase 2, spend a lot of effort planning for the next time you get to Communication Phase 3 – that is, the next teachable moment.

Communication Phase 4: Pandemic Imminent

By the time a pandemic looks imminent, WHO will definitely be in Phase 4, maybe even Phase 5. Some experts predict that the transitions through Phases 4 and 5 will be very quick: Once human-to-human transmission starts to become more efficient, they speculate, the cat will be out of the bag and a full-blown pandemic (Phase 6) will be not just inevitable but very soon. Other experts think the virus might dawdle in Phase 4 or 5 just as it has dawdled in Phase 3. A few think it might reach 4 or even 5 and stop there – either on its own (who knows why?) or because a last-ditch “fire blanket” effort (extensive use of antiviral medications at Ground Zero and a cordon sanitaire to protect the rest of us) might actually work.

In Communication Phase 4, nobody will know yet how these uncertainties will play out. The whole world will be watching.

More important still, nobody will know yet whether the pandemic that looks imminent is going to be severe or mild.

Severity will depend on many factors. Some will depend on the virus itself – how easily it spreads between humans (attack rate) and how deadly it turns out to be (case fatality rate). Others will depend on societal response – how effective non-pharmaceutical interventions turn out to be, how quickly a vaccine is developed and mass-manufactured, how well supply chains are able to cope, etc.

For awhile at the beginning, we will know that the virus is spreading more and more efficiently between humans, portending an almost certain pandemic. But our information about severity will still be fragmentary and unreliable. We will be battening down the hatches for an approaching hurricane without knowing if it is Category 2 or Category 5 – or worse.

Although it may come late in the game, Communication Phase 4 is the mother of all teachable moments. As soon as credible experts start saying a pandemic looks imminent (the defining characteristic of Communication Phase 4), people you’ve been trying to reach for years will suddenly pay attention – and they will instantly complain that you didn’t warn them earlier. Don’t get defensive; focus instead on urgent preparedness messages.

The tone of your communications should start shifting. You don’t have to arouse people’s concern any more; the situation is doing that for you. Don’t give in to the temptation to over-reassure them, either. Now the task is to validate their rising fear, help them bear it, and guide them through it.

Communication Phase 5: Pandemic Elsewhere

WHO has declared a definite pandemic. But it isn’t “here” yet. You may have only a day or two for last-minute preparations; you may have weeks; it’s conceivable, though unlikely, that you could have months before it gets here.

It’s intriguing how seldom we encounter a tabletop exercise that pays much attention to Communication Phase 5. In almost every drill we’ve seen, either the index case of the pandemic is “here” or it travels “here” at the very start of the exercise. Nobody seems to be practicing for the short but crucial period when the pandemic has undeniably started but isn’t “here” yet.

In the Pandemic Elsewhere phase, you begin to get more data about how severe the pandemic is shaping up to be. Of course that can change; flu pandemics can come in waves, and the waves can vary in severity (there’s no clear pattern – later waves can be severer or milder than earlier ones). Still, most of your Communication Phase 5 plan will depend on what you have to say about the severity of the coming pandemic.

You’ll need subplans for different severity categories. Communication Phase 5 messages for a mild pandemic will focus mostly on medical matters: symptoms, vaccines and antivirals, hospital surge capacity problems, etc. Communication Phase 5 messages for a severe pandemic will need to address much tougher worries: shortages of essential goods, disruption of essential services, threats to the social order. Of course you may have to split the difference if the pandemic’s severity is intermediate or still hard to assess. And you will have to warn people that estimates of the pandemic’s severity may turn out wrong, or may change over the course of the pandemic.

Communication Phase 6: Pandemic Here

It’s different when the pandemic gets “here” – especially if it’s severe. Of course you will have endless information and instruction to communicate, from which facilities are open to what supplies are available to how long survivors should stay home after recovering.

But in the middle of a crisis the most important communication tasks have to do with sustaining people’s ability to bear the unbearable. Validating how awful it is, demonstrating your candor and your determination (not your over-optimism), celebrating heroes and mourning victims – these are every bit as crucial as anything else you need to tell your publics.

Now is our chance to show you one of the few pandemic messages (as opposed to pre-pandemic messages) we have found. And it is an unusually good one, a message map that focuses on a metamessage of cooperation and determination. The “question or concern” is: “Human-to-human transmission of H5N1 has become efficient and sustained.”

| Key Message/Fact 3: | With the public’s cooperation we know that Americans will get through this. |

|---|

| Supporting Fact 3-1: | There may be very difficult times ahead. |

|---|

| Supporting Fact 3-2: | But America is a strong country. |

|---|

| Supporting Fact 3-3: | We have pulled together to get through tough times before and we will again. |

|---|

| Prepared for Kentucky’s Pandemic Influenza Risk Communication Training, written by Dick Tardif, Vincent Covello, and Nichole Ovens-Urban under the auspices of Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE). |

Communication Phase 7: Pandemic Elsewhere (again)

The pandemic is receding where you are. It’s time to regroup, not relax. Another wave may be coming, and it could be worse than this one was. And of course the pandemic is still raging elsewhere, and if it is a severe pandemic, supply lines are still wrecked. Regrouping won’t be easy.

As waves come and go, you may need to get through several iterations of Communication Phases 6 and 7.

Communication Phase 8: Post-Pandemic

It’s really gone. Now you need a communication effort to help everyone recover. And you have a chance to help everyone segue from debriefing what they’ve just been through to thinking about long-term preparedness.

Bear in mind that other flu strains circulating in animals could pose a pandemic threat. So maybe we’re back in WHO’s Phase 1 or 2. Or maybe we’re in WHO’s Phase 3 (or conceivably even 4) for a different strain. Here’s a communication worst case scenario: We go through a mild pandemic in the next year or two of some strain (not H5N1) that has come out of the blue. H5N1 still looms, and now we need to convince people to stay worried.

The purpose of these eight pandemic communication phases is to focus communication planning on communication issues. Before a pandemic, what matters most is picking your teachable moments, when you have the best chance to arouse public concern and action. During a pandemic, the communication phase depends on where the pandemic outbreaks or waves are – and your mid-pandemic messages depend on how severe these outbreaks or waves are. After a pandemic, the communication tasks are to help with recovery and to promote continued vigilance and preparedness for the next pandemic.

Proposed Standby Messages for an Imminent Pandemic

Our recommendations focus on Communication Phase 4, “Pandemic Imminent” (which corresponds to WHO Phases 4-5), when it first looks like a pandemic is probably on its way.

Our recommendations focus on Communication Phase 4, “Pandemic Imminent” (which corresponds to WHO Phases 4-5), when it first looks like a pandemic is probably on its way.

Communication Phase 5, “Pandemic Elsewhere,” will be largely the same, we think, with two key differences: (a) WHO will have officially declared that a pandemic is underway; and (b) More will be known about its likely severity. The messaging for Communication Phases 4 and 5 will be very similar – and very different from the pre-pandemic messaging characteristic of the current oscillation between Communication Phases 2 (“Pre-Pandemic Warm”) and 3 (“Pre-Pandemic Hot”).

By the time the pandemic gets “here,” messaging will be significantly different again. And it will be very dependent on how this particular pandemic is shaping up in this particular place. (The same metamessaging principles and strategies will apply, however.)

So for now, imagine the frightening day when WHO announces Pandemic Phase 4 or 5 – a time of increasingly efficient human-to-human transmission of a novel influenza virus.

Here is our proposed list of standby messages for that scary day.

But first we have two warnings.

First Warning:

These aren’t messages for now. They are standby messages for when WHO declares Pandemic Phase 4 or 5. As you read them, imagine yourself in that situation:

- with really bad news coming out of at least one corner of the world, and maybe several;

- with many experts publicly suggesting that it might be only a matter of days before the disease reaches our shores;

- with the pandemic story dominating the mainstream media, the blogs, and the rumor mill;

- with the real near-term risk of an influenza pandemic having just gone up a lot.

Try not to slide back into the current world of WHO’s Phase 3, when the experts’ worry strikes the public as abstract and far from urgent. Especially if you’re reading just sections of this long column, don’t forget: It is based on a future scenario that isn’t actually happening yet (at least it wasn’t in mid-March 2007 when this was first posted). We are trying to decide how to talk to people when a pandemic is imminent.

Second Warning:

We are risk communication and crisis communication experts, not virologists or pandemic policy experts. We have tried to make what follows technically solid – but we apologize in advance for technical errors that have surely crept in. As for pandemic policy, we haven’t hesitated to let our biases show – but there’s no particular reason why anyone should accept pandemic policy advice from two communication professionals. Of course readers are free to disagree with our communication advice too (and we hope some of you will take the time to challenge us about it, even if you don’t read this entire long article) … but that’s the advice we hope you will consider seriously.

Copyright © 2007 by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard