Americans have long loved progress. But, confronted daily by risks known and unknown, real and imagined, they re beginning to wonder whether enough’s enough.

They’re worried about lead in their drinking water, radon in their basements, high-tension wires strung along the edge of town, oil spills washed up on their beaches, and auto emissions polluting their air.

Many of them are angry. The growing activist movement has forced environmental grievances on corporate America. On the other side of the line, embattled company executives, facing protests and boycotts, are trying to quell or cope with this outpouring of outrage.

Too often, in aiming at solutions, they miss the mark – or shoot themselves in the foot.

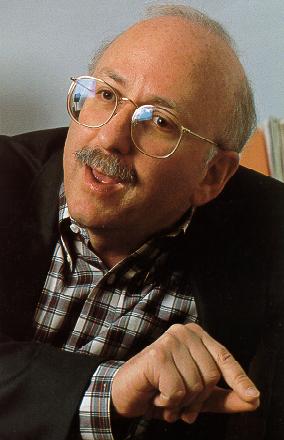

Enter Peter Sandman, the guru of gall.

If there’s one person who understands the formation and consequences of public frustration and outrage, it’s Sandman, founder of Rutgers University’s Environmental Communication Research Program in New Jersey and a well-known consultant on communicating the facts of safety and environmental risks.

Dryly, he relates his selling point: “I get hired to help a company to ‘explain to these confused people that the refinery isn’t going to blow up, so they will leave us alone.’ ”

Sandman was sought out for his expertise as early as 1979, when an investigative commission appointed by President Carter called on him in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. In the last few years, his time increasingly has been spent advising companies and government agencies who are wrangling with publics that are merely annoyed or openly enraged over products or industrial practices.

But, he insists, companies are posing the wrong question when they ask, “How can we make the public stop seeing the nature and degree of industrial risks the wrong way?” “Instead,” he says. “they should ask, What is it we’re doing that justifies this reaction?”

That’s hard advice, especially for firms, such as BP, who can be confident they have thorough emergency prevention and response procedures in place. Even then, Sandman advises, a company ignores public reaction at its own peril. Left unattended, outrage can bring down a business faster than a chemical explosion – no matter whether the physical and environmental dangers are real or merely perceived.

There’s a big difference between the two, Sandman points out. If you compare the industrial risks that pose actual, significant dangers against the risks that are slight but upset the public, you get a “miserable correlation.” He expresses the disparity in blunter terms: “The risks that kill people and the risks that honk people off are entirely different.“

Bad boy:

Oil is one of several industries traditionally portrayed by activists as environmental bad boys. It shares the honor with the chemical and hazardous waste industries. Mistrust of oil companies swelled in the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound several years ago.

“For the public, a big issue today is oil spills,” Sandman says. “Dead water fowl have become the emblem of environmental deterioration, seen as proof that humankind is not doing a good job of protecting the earth.”

Add to this the worries that have cropped up, after our long love affair with the auto, about what car emissions are doing to our air.

“People feel that driving is bad, that the internal combustion engine has done a lot of damage to our lives,” Sandman says. “But we are all very attached to our cars. It isn’t appealing to be angry at ourselves, so our guilt emerges as righteous indignation aimed at the oil industry.“

On top of the tempests over these shared concerns are local squalls where oil companies are visible because of refineries, wells, pipelines, or drilling rigs.

“It’s there that people are most worried about oil industry pollution, and it’s there that you have to concentrate your efforts,” Sandman says.

BP is in the growing circle of companies that have sought Sandman for his expertise: coaxing executives into looking at an old problem in a new way.

In Sandman’s view, that begins with a definitional dispute over the word “risk.”

Typically, he says, a company assesses risk by an old scientific formula that multiplies magnitude by probability: how bad is the risk and how likely is it? But that interpretation doesn’t wash with a public that seeks reassurance but instead feels skepticism mixed with gut-level emotions.

To acknowledge these sensitivities, Sandman says, the definition of risk should look like this:

Risk = Hazard + Outrage

Simply put, the equation defines risk not only on the basis of cold technical data but also by human standards such as trust, morality, accountability, openness, and compassion (the outrage component).

Outrage, Sandman argues, is a predictable response when a community feels it isn’t being dealt with squarely. It doesn’t matter how big or small the technical risk. It doesn’t matter that, from a technical viewpoint, people are overreacting. In Sandman’s terms, Outrage is as legitimate a part of risk as hazard.

Corporate softies:

Some business people who weigh the benefits of doing the right thing in risk communication don’t relate to reasons that are “soft.” Sandman sums it up for them in terms they easily understand: the bottom line.

“Reducing outrage is good business,” he tells them. “Outrage is expensive.”

Still, even for the company that understands the economics of outrage and tries to head off trouble, the battle can be uphill. That’s because it is equally good business for environmental groups, legislators and other players in the environmental tug-of-war to fan frustration and anger.

“Activists are in the business of generating outrage,” Sandman contends. “For the media, outrage makes a better story. Lawmakers are responsive to outrage so they can be reelected. And because legislators set the agenda for them, regulators, too, respond to outrage.”

But, Sandman teaches, business has the duty to minimize outrage. How well they do this, or whether instead they fan fears and anger, depends on how skillfully they deal with a long list of what he calls “the components of outrage.” A sampling:

- Outrage factor 1: Is the risk voluntary? Do the people in the community have a real choice about living next door to your refinery or power plant? Did they have a voice in plans to build the factory a couple blocks away? Cornered, people become more frustrated and angry.

- Outrage factor 2: Is the risk fair? The benefits of your product or service might greatly outweigh the risks. But a community won’t see it that way if it is exposed to the real or perceived risk of, say, air emissions, without reaping “adequate” benefits such as higher tax support or jobs.

- Outrage factor 3: Is the risk familiar? Perhaps oddly, the more people know about a risk, the less their outrage. If you ignore the risk, people will take it upon themselves to worry. Take a risk seriously, explain it and the precautions you’ve put in place, and they relax.

- Outrage factor 4: Who has control over the risk? A company can project these messages: “Butt out” and “Stop worrying.” But a public that has no control over a risk will do neither.

- Outrage factor 5: Is a company responsive and open? People are intolerant of secrecy and evasiveness. Stonewalling feeds suspicion. Acknowledging risks and mishaps builds credibility and trust.

Antidotes for fear, anger and damage to business, then, are honest communication and finding ways to let neighbors share in decisions that influence your business and their lives.

“It’s safe, it’s safe!”

Sandman admits the concept of shared control is difficult to sell to CEOs who “won't even share power with executive vice presidents.”

To bring home the powerlessness companies can engender in the public, he paints a vivid scenario: Two people are slicing a roast. One of them is holding the meat with an unprotected hand, the other is holding the knife.

“In the typical risk controversy, the community is holding the meat and the company is waving the knife around like a chef in a sushi restaurant, yelling, “It’s safe! It’s safe!”

Outrage begins to dissipate when companies find ways to share the knife. But how? One route is through community advisory panels or local emergency planning committees. Sandman suggests options that are more radical, too: “Put an environmentalist on your board, or commission independent audits of your environmental responsibility.”

Another possible control-sharing move: Negotiate with a community for compensation – a company-funded park, for example, or hospital improvements – for the risk the community bears. But be careful. Offering benefits can backfire if it’s perceived as bribery.

Sharing information makes sense as a means of instilling trust and easing worry. And industries have been “encouraged” to share some of this critical information through government legislation.

But companies often make one mistake: refusing to reveal worst-case scenario data – the kind their neighbors want when they ask, “How many people will die if your hydrogen fluoride unit forms an aerosol with a 30-mile-an-hour wind blowing toward Philadelphia?”

“Almost every company refuses to share its worst-case scenario data,” adds Sandman. “They say, ‘This is proprietary information,’ which is nonsense, or, ‘You wouldn’t understand and it would only alarm you,’ which is condescending.”

Sandman argues that opening up on the worst case demonstrates a company is fully aware of reality, ready to act to ensure the worst never happens, ready to move quickly to fix things if it does. Result: the degree to which such information scares people is far outweighed by the amount of credibility it creates for a firm.

“If I’m a neighbor,” he explains, “and I think that you’re taking the risk seriously, I’ll stop worrying and go bowling.”

Are such messages sinking in? After plying his prescriptions for seven years, Sandman answers yes and no.

Report card:

“I’ve seen a lot of change, but also a lot of backsliding,” he concedes. “While I’m in the room, the executives are in my thrall. They agree with everything I say. The next day, they wake up and they wonder, ‘What drug were we on that we were talking about being honest and open?’ ”

The most welcome attitude shift he has witnessed is the growing willingness of some industries to forge alliances with communities in which they do business.

“I see change in the community advisory panels that the chemical industry has everywhere. I see it in the oil industry’s increasing openness about risk assessment data.”

One example Sandman points out is BP’s Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, refinery. Instituting a new policy of openness, plant management there notifies police whenever there’s even the slightest accident or emissions leak, even when it poses no risk.

“When a neighbor calls to say, ‘I smell something funny,’ the dispatcher can say, ‘Yes, BP just called to say something happened to their olefin unit and they expect to have it cleared up within a few hours. Here’s a number you can call if you want more information.’ ”

The program worked so well that, when one neighbor phoned police about an odor, the dispatcher replied that he didn’t know what had happened, but added, “It can’t be BP or they would have called.”

In Lima, Ohio, executives from BP’s refinery and chemical plant routinely meet with local officials and citizens’ committees to share data on chemical emissions and company emergency plans to minimize them.

BP’s Lima chemical plant drilled a $4 million geological test well to confirm that waste deposited by a system of injection wells is not drifting out of its sealed, sandstone bed toward the water table or the surface. (It isn’t.) And after spending $30 million in improvements that cut air emissions in half at the Lima plants, BP announced plans to spend another $17 million to reduce them further. The plant’s actions – explained to Lima’s residents – have met with widespread approval.

Spotting the phonies:

Oil companies including BP, still have a lot of work ahead of them in such efforts to short-circuit fear and anger, acknowledges Sandman. But he adds, “these kinds of victories are sizeable.”

He believes the chemical industry has made the most progress. He attributes this in part to Union Carbide’s Bhopal tragedy, which preceded the Valdez oil spill by several years. He also gives high marks to the chemical industry’s trade representatives.

“Most often, trade associations represent, rather than push, their industries. The Chemical Manufacturers Association is leading the industry instead of following it.”

Still, he adds, “Policies change before practices, and practices change before attitudes. I see a lot of companies whose policies are pretty good, but whose practices are mediocre, and whose attitudes are dinosaurs.”

But the end of outrage-control’s dinosaur age may be in sight as more and more companies find they must reexamine their attitudes, he adds. Though progress is slow, Sandman believes it is real, even though activists are impatient and skeptical.

“It’s easy to mistake the angst of an organization that’s trying to change for the hypocrisy of one that’s pretending to change,” he says.

“There are a lot of morning-after lapses. but what’s left are a lot more people in industry who are willing to have the dialogue.”

Copyright © 2001 by Shield (the BP Amoco Group)